04 Jul 2020

Explained by Zack Lerangis in his introductory video on patronage:

What is patronage? … It’s a kind of relationship in which you have a patron and a client: the patron provides favors to the client … in exchange for the client’s support, especially political allegiance.

A particular person can be in many different patronage relationships, and they can and often do fulfill both roles. You can have a patron who has multiple clients, who themselves have multiple clients – and you can have two patrons who are allied, who share clients. The result of all this is an interlocking web of patronage which you can call a patronage network. These patronage networks can be very powerful social and political entities: they can take control of institutions, and they can have a tremendous influence through this means on their society.

People often think of political parties as unified by shared ideology, and although shared ideology is an important part of their functioning, what’s actually more fundamental usually is patronage. …. The particular politician is very often motivated much more by personal interests than by ideological commitments.

He expands on this by describing how patronage shapes ideology itself:

The common view here is that the ideologies of political parties are these natural worldviews, … and the people who make up the political party coalesce around them and that forms the basis of the party. Instead, I think the way it works is that the different components of the political coalition that makes up the party each have their own ideologies, and these different component ideologies are often not compatible. But nonetheless, these different coalition members come together because of a shared political interest, even if they don’t agree on everything about the way the world works or the way the world should be. In order to reconcile or patch over these ideological differences, the different component ideologies are stitched together into this patchwork in which the differences between them are suppressed or not brought to the forefront of people’s attention.

Another corollary of this is that ideologies need a strong institutional basis in order to spread and in order to take hold politically. A lot of people think that if they can just find the true ideology, and if they can communicate it to people clearly, then it will naturally spread throughout society. It would be great if this were the case, but in fact, an ideology needs to have a strong institutional basis in order to spread and in order to make its way into the core institutions of a society.

Some examples of this system of patronage are described in the Interest Group Advocacy and Role of Public Opinion in Policy Making models.

03 Jul 2020

Explained in both essay and video formats by Samo Burja:

Everyone has an implicit theory of history– usually inconsistent across time periods and typically incoherent without explication and conscious work, it will nonetheless be the basis of much of your action in the world. Most people never discover theirs simply because they don’t realize they’re acting on one. Now that you have the concept– what is yours?

15 Mar 2020

Summary

Status quo policies and incumbent politicians often have a systemic advantage in the political arena.

Context

Some examples from Interest Groups and Lobbying:

Supreme Court

In sum, when public interest groups are the challengers of the status quo, there is little evidence that they are getting anywhere at the Supreme Court. Of course when it comes to the consumer protection and environmental laws that these groups convinced Congress to enact in the 1960s and 70s, they are the ones defending the status quo, and they have the advantage. Basically the judiciary is a conservative institution in that judges and justices defer to the legislative and executive branches when they can, so challenging any policy status quo in the judiciary is an uphill battle. The payoff is enormous when successful, but it is a significant gamble of time and resources. … Petitioner groups win far more than respondent groups, but remember that in an appellate court it is likely that the petitioner group was originally the respondent and is actually defending the status quo! It is a common lesson in this book: status quo policies are hard to overthrow.

Negotiations between interest groups

Context:

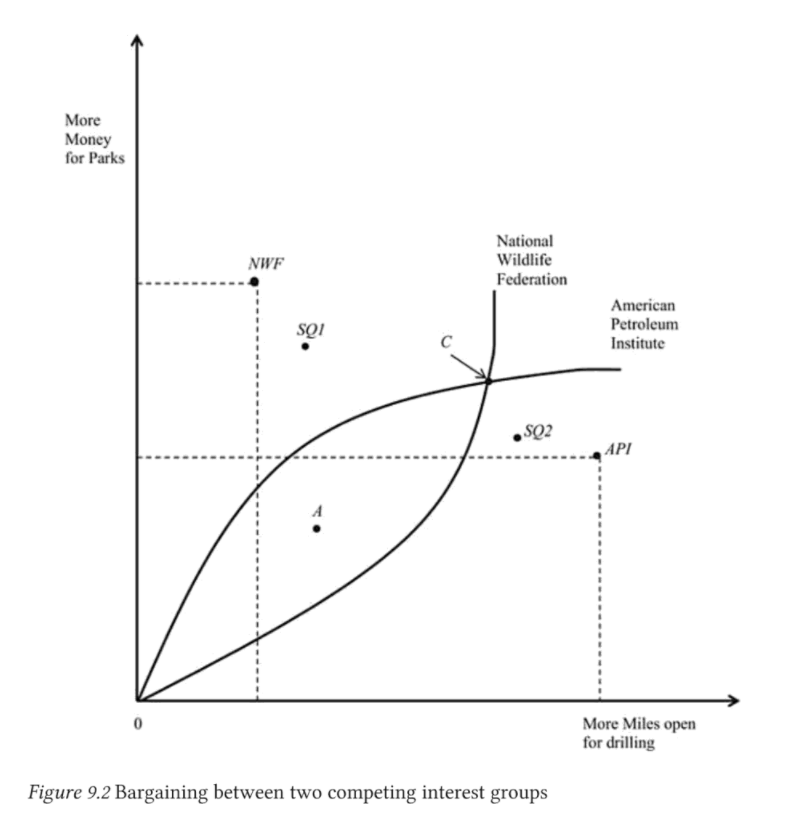

- When the government leases land for oil drilling, it receives a royalty

- In this example, the National Wildlife Federation and the American Petroleum Institute are competing over the issue of how much of this money should be spent on parks

- The NWF and its members want more money for parks and less miles for drilling; the API wants the opposite

- Each respective group’s ideal policy is at the points labeled NWF and API, though each group would never agree to the other’s ideal position

- The solid curved lines represent the maximum trade-off that each interest group’s members will tolerate

- Point C represents the best possible compromise between the two groups

It becomes more complicated if a status quo policy already exists, and it usually does. Say point SQ1 in Figure 9.2 is the current policy and provides NWF with more money for less drilling than the API’s lobbyist would accept because it is higher on the vertical axis than the API’s curve. SQ1 is closer to NWF than it is to point C, so the NWF’s lobbyist will not bargain with the API because he or she knows the status quo is better than anything API will agree to. In other words, there can be no bargain in this scenario, and the NWF will fight to preserve the status quo. If the status quo was SQ2, then the NWF’s lobbyist would jump at the compromise at point C because it gives his or her members more of what they want than the status quo. But the API lobbyist would not support a deal at C because the status quo (SQ2) is closer to what his or her members ideally want. So bargaining and coalition building depend on what trade-offs members will tolerate and what the alternatives to not bargaining are, including the status quo.

In interest group negotiations like this, the status quo provides an advantage to whichever side it benefits most, since it bends the range of acceptable compromises towards the side of the status quo holder.

Campaign contributions

It takes money to raise money in politics. Raising money early is crucial to elected officials, especially challengers, though incumbents use early money to discourage potential challengers (Jacobson 1992). PAC leaders understand this, and some, like EMILY’s List, specifically contribute early to help favored candidates raise more money down the line (Box-Steffensmeier, Radcliffe, and Bartels 2005). Most PACs, though, are conservative about contributing early because they want to back winners. It is another reason why they favor incumbents (who nearly always win) and are often unwilling to take chances on challengers unless challengers show early on that they can win, usually through aggressive fundraising. For candidates challenging incumbents, this PAC mind-set makes raising money extremely difficult. More ideological, nonconnected PACs and super-PACs, however, are more likely to take risks on challengers who embrace their ideological positions. Non-ideological PACs, however, are only likely to give money early when a partisan wave is building that might change the balance of power, as happened in 1980 (Eismeier and Pollock 1986), 1994, and 2010.

15 Mar 2020

Summary

If a social movement succeeds in cracking open the political system, it must then learn to play by the rules of the institution it has worked to crack.

Context

From Interest Groups and Lobbying:

If a social movement succeeds in cracking open the political system, it must then learn to play by the rules of the institution it has worked to crack. Movements rearrange some of the pieces of the power structure that supported policies at the root of their grievance, forcing back older, more entrenched interests by making them accept the legitimacy of the movement’s demands. They add their interest to the array of interests deemed worthy of government support, expanding the range of policy problems receiving government redress. This success is significant, but victory comes with costs, which may not be immediately apparent to the organizers of the social movement, who are now looking at careers as lobbyists. They must play by the rules and norms of the game they have struggled to join. The movement changed the beneficiaries of public policy and the values it enshrines, but not the way it is made. Activists-turned-lobbyists are now expected to work with lawmakers through the regular, institutionalized procedures of the political system. Bills will be introduced, other members of Congress will be lobbied, information packets developed, email campaigns launched—all with a united message that benefits their new legislative allies as much as their members. Other interest groups must be recruited as allies or bargained with as opponents. Because operating on the inside is much cheaper than staging protests, the groups staff are usually happy to oblige.

Passionate, dedicated movement members may not understand this transformation. They may not understand that further pursuing their interests now requires compromises with competing interests and paying attention to the needs of lawmakers. They may not understand the growing gulf between themselves and their leaders as the latter become part of the Washington social scene. While in many cases this simply leads to the loss of dispirited, disillusioned members, political scientist Anne Costain (1981) describes a much more dramatic result. At the 1975 national convention of the National Organization of Women (NOW), members forced out much of NOW’s Washington staff for the crime of playing by Washington’s rules, even though the professional activists had learned how to use them to the members advantage.

Social movements are therefore embryonic interest groups, though not all interest groups start as social movements. The trade and professional associations representing businesses and white-collar professions certainly did not start out as street protests. Citizen groups, on the other hand, often started out as some kind of social movement, their origins grounded in passionate political activism. Sometimes they still try to keep the trappings of it and fire up large numbers of members just to keep them involved in the group. Of course the real difference between the two is that social movements represent interests truly excluded from regular politics but who have the opportunity and resources to break in, whereas interest groups are already on the inside.

15 Mar 2020

Simple definition from Wikipedia:

Governments hire industry professionals for their private sector experience, their influence within corporations that the government is attempting to regulate or do business with, and in order to gain political support (donations and endorsements) from private firms.

Industry, in turn, hires people out of government positions to gain personal access to government officials, seek favorable legislation/regulation and government contracts in exchange for high-paying employment offers, and get inside information on what is going on in government.

The lobbying industry is especially affected by the revolving door concept, as the main asset for a lobbyist is contacts with and influence on government officials. This industrial climate is attractive for ex-government officials. It can also mean substantial monetary rewards for the lobbying firms and government projects and contracts in the hundreds of millions for those they represent.

From Interest Groups and Lobbying:

As noted above, 80 percent of lobbyists came into lobbying from government jobs. Lobbyists told Heinz and his colleagues that government service helped launch their lobbying careers. Of the lobbyists interviewed, 70 percent said it gave them familiarity with issues, 80 percent said it taught them how the lawmaking process works, 59 percent said it gave them important contacts in Congress, 48 percent said it gave them contacts in the administration, and 47 percent said it helped them gain contacts with other lobbyists (Heinz et al. 1993, 115).

This is what is colloquially called the revolving door. Many ex-Hill people end up at well-known lobbying firms such as the Podesta Group (which has the most ex-Hill staff at eighteen, according to Washington Representatives 2010, vii) and major interest groups such as the US Chamber of Commerce.

Why? Tony Podesta, founder of the Podesta Group, told the Washington Post that “people who are experienced in Washington tend to be better at doing this kind of work than people who have never worked in the government before.” Often the reason is strategic. The Motion Picture Association of America hired former senator Chris Dodd (D-CT) to be its new president because for years Dodd had chaired the Senate committee that controlled many of the policies important to the group (Romm 2011). Conflicts of interest? Maybe. Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington found in 2011 that seven ex-congressmen were now lobbying for interests these legislators had supported with government appropriations while in Congress (Farnam 2012b).

The hiring of ex-legislators and legislative staffers as lobbyists (and the issue of who gets hired) has become a political issue. Interest groups and lobbying firms try to staff up with lobbyists of the same ideological persuasion as the party controlling Congress. For example, Republican staff members were in high demand in 1994 after their party gained control of the House and Senate (Stone 1996). Party leaders even threatened to shut several interest groups out of Congress if they did not hire Republican staff as lobbyists.

In the past, well-connected lobbyists … could easily work with both parties, bringing competing groups of interests together to hammer out deals and resolve conflicts (Ignatius 2000). Today, though, lobbyists are pressured by the parties to take sides, with their access threatened (which kills a lobbyist’s career) if they do not.

Perhaps even more interesting is that 605 congressional staffers in 2011 used to be lobbyists. When Republicans took over the House of Representatives that year, many new legislators recruited their senior staff from among the ranks of major lobbying firms and business associations (Farnam 2011). The door fully revolves. Government workers leave to make money as lobbyists, and some later return to work on the inside, possibly still biased toward the interest groups that recently employed them, and they could return to lobbying again in a couple of years for a lot more money.