21 Oct 2020

Academia and industry play vital roles in advancing standards of living. What are their respective responsibilities/contributions, and how do they overlap and interact?

Academia

From Economics for the Common Good, an academic/researcher contributes the following to society:

- Create knowledge; define the truth

The duty of an academic is to advance knowledge. In many cases (mathematics, particle physics, the origins of the universe) perhaps we should not be too preoccupied with the application of knowledge, but only with finding the truth – applications will come later, often in unexpected ways. Research driven only by the thirst for knowledge, no matter how abstract it may be, is indispensable – even in the disciplines that are naturally closest to real-world applications. But academics must also collectively aim to make the world a better place …

In the cutting edge of the field, there’s a lack of consensus in this knowledge/truth, and that’s ok:

… these labels cause economics to run the risk of being perceived as a science with no consensus on key questions, meaning economists’ views can be safely ignored. This overlooks the fact that, although their personal opinions may be different, leading economists agree on many subjects – at the very least on what must not be done, even if they do not agree on what should. This is just as well. If there were no majority opinion, financing research in economics would be hard to justify, despite the colossal importance of economic policies. However, research and professional debate concern questions economists understand less well – this is what is distinctive about research – and that are therefore likely to inspire only limited consensus. And it goes without saying that professional consensus can, and should, develop as the discipline advances.

The relationship between universities and industry is often controversial. … These interactions with the real world, however, are probably one of the best ways for academics to understand the problems facing the economy and society, and to develop and fund relevant, original topics of research that those who stay cloistered in their ivory towers could never imagine.

The economics community can be overly focused on areas of “intensive research” – the kind that refines existing knowledge – while neglecting fundamental topics staring practitioners in the face, because researchers have not done enough extensive or broad-ranging research of the kind that is needed to explore new scientific territories.

Whatever area of economics they pursue, there are two ways in which researchers can influence debate on economic policy and the choices made by businesses (there is no single good model, and we all act in accordance with our own temperament). The first is by getting involved themselves. Some, overflowing with energy, succeed in doing so, but it is rare that a researcher can continue to do extensive research and be very active in public debate at the same time. The second way is indirect: economists employed by international organizations, government ministries, or businesses, read the work of academics and put it to use. Sometimes this work is a technical research article published in a professional journal; sometimes it is a version written for the general public.

- Offer expert opinions, balancing between summary and detail

Researchers have an obligation to society to take positions on questions on which they have acquired professional competence. For researchers in economics, as in all other disciplines, this is risky. Some fields have been well explored, others less so. Knowledge changes, and what we think is correct today could be reevaluated tomorrow.

Finally, even if there is a professional consensus, it is never total. Ultimately, a researcher in economics can, at most, say that, given the current state of our knowledge, one option is better than another. … Thus academics must maintain a delicate balance between necessary humility and the determination to convince their interlocutors of both the usefulness of the knowledge they have acquired and its limits. This is not always easy, because others will find certainties easier to believe.

The media is not, however, a natural habitat for an academic. The distinctive characteristic of academics, their DNA, is doubt. Their research is sustained by their uncertainty. The propensity for putting forward arguments and counterarguments – as academics systematically do in specialized articles, in a seminar, or in a lecture hall – is not easily tolerated by decision makers, who have to form an opinion rapidly. … But above all, academic reasoning is ill adapted to the format of television or radio debates. Slogans, sound bites, and clichés are easier to put across than a complex argument concerning the multiple effects of a policy; even weak arguments are difficult to refute without engaging in a long explanation. Being effective often means acting like a politician: you offer a simple – or even simplistic – message, and stick to it. Do not misunderstand me: academics should not try to hide behind scientific uncertainty and doubt. As far as possible, they must reach a judgment. To do that, they have to overcome their natural instincts, put things in perspective, and convince themselves that, in these circumstances, some things are more probable than others: “In the present state of our knowledge, my best judgment leads me to recommend …” They have to act like a doctor deciding which treatment is best, even in the face of scientific uncertainty.

… the relationship between the scientific and the political is uncomfortable, even though many politicians show some intellectual curiosity. Academics’ and politicians’ time horizons differ, as do the constraints they face. The researcher’s role is to analyze the world as it is and to propose new ideas, freely, without the constraint of having to produce an immediate result. Politics necessarily lives in the present, always under the pressure of the next election. However, these very different time pressures, in response to very different demands, cannot justify a visceral mistrust of the political class. Academics can help politicians make decisions by providing them with tools for reflection, but cannot take their place.

Though these opinions often fall victim to the bias of the audience:

… the academic with a political message is quickly pigeonholed (“left-wing,” “right-wing,” “Keynesian,” “neo-classical,” “liberal,” “anti-liberal”) and the labels will be used to either support or discredit what he or she says, as if the role of a researcher, in any discipline, was not to create knowledge, disregarding preconceived ideas and labels. The audience all too often forgets the substance of the argument, instead judging the conclusion on the basis of their own political convictions. They will welcome the argument favorably or unfavorably depending on whether the academic seems to be on their side or not. In these circumstances, an academic’s participation in public debate loses much of its social utility. It is already difficult enough to avoid being drawn into politics. For example, when a question is about a technical subject on which the government and the opposition disagree, the academic’s every response will be quickly interpreted as a political position. This can inadvertently drown out the message and prevent it from contributing to an enlightened debate.

These responsibilities are also expressed in the keynote speech of the 2017 Marie Curie Alumni Association AGM.

Industry

On the other hand, a practitioner in the industry will:

- Turn knowledge into useful products and services

From The Role of Business in Society:

This then is the role of business in society: to innovate and deliver products and services, to use resources efficiently so that value is created and to conduct operations so that they are performed profitably and accepted by society.

If companies did not exist and you wanted a means for delivering innovation, you would have to create them. In competitive markets, the ability to innovate—whether in technology, management, products or services—is central to the survival of the company. Innovation involves new sciences and technologies, access to raw materials and, in some cases, finite resources. It may involve new ways of working and patterns of organisation. These are often contentious areas that are within the law but breaking new ground.

- Contribute to larger social goals via corporate social responsibility and active involvement in society

CSR, including consideration of environmental sustainability, has evolved in recent years as a coherent way of thinking about a company’s impact and interaction with society. It covers subjects that affect all companies, such as employment standards, equal opportunities, diversity and carbon emissions; as well as those that are specific to a particular industry, such as advertising to children, drug pricing, nanotechnology or sustainable use of water. It includes those that may affect only a single business, for example, a specific local environmental or community impact, or the consequences of a particular sourcing or employment policy.

For the CEO and Board the challenge is to have a clear map of their business’s impact on and interactions with society, a way of exploring and agreeing the company’s approach to the challenges these raise, and then a way of ensuring that business operations and performance carry through the direction provided by their leadership. It’s a question of joining up corporate purpose, principles, strategy and governance with daily management practice throughout the organisation, including relations and communications with all the company’s stakeholders. It’s about proactively managing the company’s role in society, rather than having others do it for you.

Overlap

There’s not a hard line between these roles; universities often have entrepreneurial arms and corporations often have in-house researchers. Interactions between academics and industry professionals are critical to either institution’s success, which often result in aspects of academia being embedded in industry, and vice-versa.

05 Oct 2020

Often referred to as the greatest challenge of our time, climate change is a complex issue with disastrous consequences. Formulating a solution requires a multidisciplinary approach: solutions are confined by the physical realities of nature and our current technology, the economic cost of implementation, and the political will to act. A multitude of concurrent solutions will be necessary to confront the problem, though proposed solutions differ in effectiveness and cost.

This post is my attempt to summarize my current understanding of the issue, and evaluate the commonly proposed solutions. For convenience, I often quote two books that were influential in building my understanding (Enlightenment Now and Economics for the Common Good), though the same ideas can be found in many other sources.

Advocated solutions

While there is no silver bullet climate solution, a combination of the following solutions are necessary to reach an acceptable level of global warming. These solutions are rooted in rationality, effective at scale, and should be part of the path forward.

Carbon pricing

Carbon pricing sets the foundation for climate policies by forcing economic agents to pay for the emissions they produce. Its global implementation is imperative for reaching an acceptable level of warming, as agents will otherwise free-ride on the efforts of others and leak emissions into cheaper areas of production. The price of emissions (and ultimately the cost of this policy on society) is reduced by complementary technological solutions that provide abundant sources of clean energy.

Enlightenment Now presents an overview of the solution:

[Deep decarbonization] begins with carbon pricing: charging people and companies for the damage they do when they dump their carbon into the atmosphere, either as a tax on carbon or as a national cap with tradeable credits. Economists across the political spectrum endorse carbon pricing because it combines the unique advantages of governments and markets. No one owns the atmosphere, so people (and companies) have no reason to stint on emissions that allow each of them to enjoy their energy while harming everyone else, a perverse outcome that economists call a negative externality (another name for the collective costs in a public goods game, or the damage to the commons in the Tragedy of the Commons). A carbon tax, which only governments can impose, “internalizes” the public costs, forcing people to factor the harm into every carbon-emitting decision they make. Having billions of people decide how best to conserve, given their values and the information conveyed by prices, is bound to be more efficient and humane than having government analysts try to divine the optimal mixture from their desks. … Without carbon pricing, fossil fuels—which are uniquely abundant, portable, and energy-dense—have too great an advantage over the alternatives.

Economics for the Common Good provides a detailed economic analysis:

The heart of the climate change challenge lies in the fact that economic agents are not internalizing the damage they cause to others when they emit GHGs. To resolve this free rider problem, economists have long proposed forcing economic agents to internalize the negative externalities of their CO2 emissions. This is “the polluter pays” principle. To achieve this, the price of carbon would have to be set at a level compatible with the goal of limiting the global temperature rise to 1.5 to 2 degrees Celsius, and all emitters would be compelled to pay the established price: given that all CO2 molecules produce the same marginal damage, no matter who emits them, or where or how they are emitted, the price of any ton of CO2 must be the same. Imposing a uniform price for carbon on all economic agents throughout the world would guarantee the implementation of any mitigating policies whose cost was lower than the price of carbon. A uniform price for carbon would thus guarantee that the reduction of emissions necessary to achieve the global objectives for atmospheric CO2 would occur, and would minimize the overall cost of the efforts made to achieve it.

This indicates a global implementation is necessary for carbon pricing to be effective, which is explained in further detail:

Every country acts first of all in its own interest, on behalf of its people, while at the same time hoping to benefit from efforts made by other countries. For an economist, climate change is a “tragedy of the commons.” In the long term, most countries would benefit enormously from a reduction in global GHG emissions, because global warming will have large economic, social, and geopolitical effects. The incentive for each individual country to undertake this reduction, however, is negligible. In reality most of the benefit from efforts made by any country to attenuate global warming will go to other countries.

Finding a solution to the problem of global externalities is complex, because there is no supranational authority able to implement and enforce the standard approach for managing a common good by internalizing external costs … as recommended by economic theory.

The problem of “carbon leakage” may further discourage any country or region that wanted to adopt a unilateral strategy of alleviation. Taxing carbon emissions imposes additional costs on national industries and undermines their ability to compete if these industries emit large quantities of GHGs and are exposed to international competition. In any given country, a carbon tax high enough to contribute effectively to the battle against climate change would thus lead some companies to relocate their production facilities abroad—to regions of the world where they could pollute more cheaply. If they did not do this, they would lose their markets (domestic or export) to companies located in countries more lenient about emissions. Consequently, a unilateral policy shifts production to less responsible countries, which leads, de facto, to a simple redistribution of production and wealth without any significant environmental benefit.

This problem of leakage provides further proof that only a global accord can resolve the climate question: countries that do not penalize carbon emissions pollute a great deal, not only producing goods for their own consumption, but also for export to more virtuous countries.

Voluntary agreements to decarbonize fall short due to “zero ambition” commitments:

Why do countries take unilateral action? Any action in favor of the climate is surprising if one considers that, as always in geopolitics, national interest comes first. Why would a country sacrifice itself in the name of humanity’s well-being? First, if there is a “sacrifice,” it is tiny: current measures remain modest and will not be enough to avert a climate catastrophe. Second, it may not be a sacrifice if the countries concerned gain other benefits from an environmental policy.

Actions to reduce the carbon content of production do not necessarily signal awareness of the impact of emissions on the rest of the world. These unilateral measures are called “zero ambition” measures. “Zero ambition” refers to the level of commitment that a country would choose solely to limit the direct effects of pollution on the country itself. In other words, it is the level the country would have chosen in the absence of any international negotiation. These measures are insufficient to keep global warming under control.

The Kyoto Protocol was full of good intentions, but that did not prevent countries from free riding. We can say the same of the non-binding promises made in Copenhagen, but for a different reason. … the conference resulted in a profoundly different project: a “pledge and review” process. The United Nations has since merely rubber-stamped, without imposing any real constraints, the informal commitments of the countries that signed up, the INDCs (Intended Nationally Determined Contributions). … The strategy of voluntary commitments has several significant defects [greenwashing, free-riding, and non-credibility of promises], and is an inadequate response to the climate change challenge.

In short, the INDC commitments have been a potluck to which each country brought what suited it best. … The INDC commitments, even if they are credible, remain voluntary, and the free riding problem is therefore inevitable. As Joseph Stiglitz pointed out, “In no other area has voluntary action succeeded as a solution to the problem of the undersupply of a public good.” In some ways, the mechanism of voluntary commitments resembles an income tax system in which each household would freely choose the level of its fiscal contribution. Many observers therefore fear that the current INDCs are merely “zero ambition” agreements.

Though, as mentioned, carbon pricing will be difficult to mandate globally, due to the lack of authoritative international governance. However, there is still hope for reaching an international agreement through sanctions and incentives:

To succeed, [carbon taxes and tradable emissions permits] depend on an international agreement that covers global emissions sufficiently, using an “I will if you will” approach. Both require implementation, monitoring, and verification (more generally, the precondition for any effective action to reduce emissions would be to establish credible and transparent mechanisms to measure their emissions). Economists do not agree on the choice between a carbon tax and tradable emissions permits, but in my opinion, and in that of most economists, either approach is clearly more effective than the current system of voluntary commitments.

An effective international agreement would create a coalition within which all countries and regions would apply the uniform carbon price to their respective territories. According to the principle of subsidiarity (the devolution of decision making to the lowest practical level), each country would then be free to devise its own carbon policy, by creating a carbon tax, a tradable emissions permits mechanism, or a hybrid system, for example. The free rider problem would be a challenge to the stability of this grand coalition: Could we count on the agreement being respected? It is a complex problem, but a solution is not out of reach.

Government debt is an instructive analogy. Sanctions against a country in default are limited (fortunately, gunboat diplomacy is no longer an option), which has led to concerns about whether countries are willing to repay debt. The same goes for climate change. Even if a good agreement were reached, there would be limited means to enforce it. The public debate about international climate negotiations usually ignores this reality. That said, we have to pin our hopes on a binding agreement, a genuine treaty, and not an agreement based only on promises. No matter how limited the possibility of international sanctions in the event of nonpayment of government debt, most countries do usually repay. More generally, the Westphalian tradition (that is of treaties between nation states being largely observed) gives us a nonnegligible chance of achieving it.

Naming and shaming is a good, feasible tactic, but—as we have seen in the case of the Kyoto commitments—it may remain largely toothless. Countries will always find excuses for not fulfilling their commitments: citing other measures (such as green research and development), recession, insufficient efforts made by others, a change of government, safeguarding jobs. There is no perfect solution to the problem of enforcing an international agreement, but we have at least two tools.

First, countries value free trade; the WTO might consider that the nonrespect of an international climate agreement is equivalent to environmental dumping, and impose sanctions on those grounds. In the same spirit, punitive taxes on imports could be used to penalize countries who do not participate. This would encourage hesitant countries to join the agreement and would make it more likely that a global coalition for the climate could be stable. Clearly the nature of the sanctions could not be decided by countries individually—they would quickly seize the opportunity to set up protectionist measures that would not necessarily have much connection with environmental reality.

Second, a climate agreement should be binding on a country’s future governments, like sovereign debt. The IMF could be a stakeholder in this policy. For example, in the case of a tradable emissions permits system, a shortage of permits at the end of the year would increase the national debt, and the conversion rate would be the current market price. Naturally, I am aware of the risk of collateral damage that could result from choosing to connect a climate policy with international institutions that are working decently well. But what is the alternative? Supporters of nonbinding agreements hope that goodwill will be enough to limit GHG emissions. If they are right, then incentive measures initiated through collaboration with other international institutions will suffice, a fortiori, without any collateral damage to these institutions.

Although it is important to maintain a global dialogue, the UN process has shown predictable limits. Negotiations between 195 nations are incredibly complex. We need to create a “coalition for the climate” that brings together, from the outset, the major polluters, present and future. I don’t know whether this should be the G20 or a more restricted group: in 2012, the five biggest polluters—Europe, the United States, China, Russia, and India—represented 65 percent of worldwide emissions (28 percent for China and 15 percent for the United States). The members of this coalition could agree to pay for each ton of carbon emitted. At first, no attempt would be made to involve the 195 countries in the global negotiation, but they would be urged to join in. The members of the coalition would put pressure on the WTO, and countries that refused to enter the coalition would be taxed at borders. The WTO would be a stakeholder on the basis that nonparticipants are guilty of environmental dumping; to avoid undue protectionism by individual countries, it would contribute to the definition of punitive import duties.

Evaluating the feasibility of this plan exceeds my expertise, and though I’m a bit skeptical, it inspires hope that an agreement could be reached in lieu of international authorities. Implementation strategies (specifically, negotiations for reaching a global agreement) are explored further in Global Carbon Pricing.

Even when enforced globally, carbon pricing poses serious concerns regarding domestic and international inequality, which must be systematically addressed. These concerns are highlighted in Enlightenment Now:

Carbon taxes, to be sure, hit the poor in a way that concerns the left, and they transfer money from the private to the public sector in a way that annoys the right. But these effects can be neutralized by adjusting sales, payroll, income, and other taxes and transfers. (As Al Gore put it: Tax what you burn, not what you earn.) And if the tax starts low and increases steeply and predictably over time, people can factor the increase into their long-term purchases and investments, and by favoring low-carbon technologies as they evolve, escape most of the tax altogether.

And elaborated on in Economics for the Common Good:

The question of inequality arises both within and across countries.

On the domestic level, it is sometimes objected that taxing carbon will be hard on the poor. Putting a price on carbon reduces the purchasing power of households, including the poorest ones, and this might be an obstacle to implementing the policy. This is true, but it should not block the environmental objective. There must be an appropriate policy tool associated with each separate policy objective, and it is important to avoid trying to achieve many objectives with one lever (such as a carbon price). So far as inequality is concerned, the state should use income tax as much as possible to redistribute income, while at the same time pursuing a suitable environmental policy. Environmental policy should not be diverted from its primary objective in order to address (legitimate) concerns about inequality. Refraining from pricing carbon to tackle inequality would be unwise.

The same principle applies internationally, where it is better to organize lump-sum transfers to poor countries rather than trying to adopt inefficient, and thus not very credible, policies. … Poor and emerging countries rightly point out that rich countries have financed their industrialization by polluting the planet, and that they want to achieve a comparable standard of living. … This has led some people to argue for a “fair because differentiated” approach: a high carbon price for developed countries and a low one for emerging and developing countries.

But … a high carbon price in developed countries would have only a limited effect because they would offshore production to countries with low-cost carbon … And even ignoring leakages, no matter what efforts were made by the developed countries, the objective of limiting the temperature increase to 1.5 to 2 degrees Celsius will never be reached if poor and emerging countries do not limit their GHG emissions in the future. It is impossible to exonerate lower-income countries.

So what can we do? Emerging countries have to subject their citizens and enterprises to a substantial carbon price (ideally, the same price as elsewhere in the world). The question of equality should be addressed by financial transfers from rich countries to poor countries.

Of course, in negotiations involving 195 countries it is difficult to agree on who is to benefit and who is to pay and how much. Each country will want to have its say and will slow down negotiations by asking to pay a little less or to receive a little more. It will probably be necessary to negotiate rough formulas based on a few country parameters (income, population, present and foreseeable pollution, sensitivity to global warming, for example) rather than trying to determine the contributions country by country. This will be difficult, but will be more realistic than an across-the-board negotiation.

Finally, is it fair that the pollution caused, in China for example, by the production of goods exported to the United States and Europe be counted as Chinese pollution, and be covered by the system of permits to which all countries, including China, would be subject? The answer is that Chinese firms that emit GHGs when they produce exported goods will pass the price of carbon through to American and European importers so that rich country consumers will pay for the pollution their consumption induces. International trade does not alter the principle that payment should be collected where emissions are produced.

In summary:

Every international agreement must satisfy three criteria: economic efficiency, incentives to respect commitments, and fairness. Efficiency is possible only if all countries apply the same carbon price. Adequate incentives require penalties for free riders. Fairness, a concept defined differently by each stakeholder, should be achieved through lump-sum transfers.

The answer to the question, “What can we do?” is simple: get back on the path of common sense.

- The first priority of future negotiations ought to be an agreement in principle to establish a universal carbon price compatible with the objective of no more than a 1.5 to 2 degrees Celsius increase in average global temperatures. Proposals seeking carbon prices differentiated on the basis of country not only open a Pandora’s box, they are above all not good for the environment, because the future growth of emissions will come from emerging and poorer countries. Underpricing carbon in these countries will not limit warming to a 1.5 to 2 degrees increase. This is so all the more because high prices for carbon in developed countries will encourage the offshoring of production facilities that emit GHGs to countries with low carbon prices, thus nullifying the efforts made in wealthy countries.

- We also have to reach an agreement on an independent monitoring infrastructure to measure and supervise emissions in signatory countries, with an agreed governance mechanism.

- Finally, and still in the spirit of returning to fundamentals, let us confront head-on the question of equity. This is a major issue, but any negotiation must face it, and burying it in the middle of discussions devoted to other subjects does not make the task any easier. There must be a negotiating mechanism that, after the acceptance of a single price for carbon, focuses on this question. Today, it is pointless to try to obtain ambitious promises for green funds from developed countries without that leading in turn to a mechanism capable of achieving climate objectives. Green financial assistance could take the form either of financial transfers or, if there is a world market for emissions permits, of a generous allocation of permits to developing countries.

There is no other way forward.

Clean technology R&D

While technological solutions should not be relied upon to save us from the climate crisis, there are massive opportunities to reduce emissions by creating economies of scale for low-emissions equipment and energy sources. Once clean technologies are cheaper than their dirtier alternatives, this creates a (self-interested) economic incentive to lower costs by switching to clean technologies, ultimately reducing emissions and the cost of carbon in a carbon pricing scheme.

Enlightenment Now describes the opportunities in mass-produced nuclear power:

Still, nuclear power is expensive, mainly because it must clear crippling regulatory hurdles while its competitors have been given easy passage. Also, in the United States, nuclear power plants are now being built, after a lengthy hiatus, by private companies using idiosyncratic designs, so they have not climbed the engineer’s learning curve and settled on the best practices in design, fabrication, and construction. Sweden, France, and South Korea, in contrast, have built standardized reactors by the dozen and now enjoy cheap electricity with substantially lower carbon emissions.

For nuclear power to play a transformative role in decarbonization it will eventually have to leap past the second-generation technology of light-water reactors. (The “first generation” consisted of prototypes from the 1950s and early 1960s.) Soon to come on line are a few Generation III reactors, which evolved from the current designs with improvements in safety and efficiency but so far have been plagued by financial and construction snafus. Generation IV reactors comprise a half-dozen new designs which promise to make nuclear plants a mass-produced commodity rather than finicky limited editions. One type might be cranked out on an assembly line like jet engines, fitted into shipping containers, transported by rail, and installed on barges anchored offshore cities.

The benefits of advanced nuclear energy are incalculable. Most climate change efforts call for policy reforms (such as carbon pricing) which remain contentious and will be hard to implement worldwide even in the rosiest scenarios. An energy source that is cheaper, denser, and cleaner than fossil fuels would sell itself, requiring no herculean political will or international cooperation. It would not just mitigate climate change but furnish manifold other gifts. People in the developing world could skip the middle rungs in the energy ladder, bringing their standard of living up to that of the West without choking on coal smoke.

Breakthroughs in energy may come from startups founded by idealistic inventors, from the skunk works of energy companies, or from the vanity projects of tech billionaires, especially if they have a diversified portfolio of safe bets and crazy moonshots. But research and development will also need a boost from governments, because these global public goods are too great a risk with too little reward for private companies. Governments must play a role because, as Brand points out, “infrastructure is one of the things we hire governments to handle, especially energy infrastructure, which requires no end of legislation, bonds, rights of way, regulations, subsidies, research, and public-private contracts with detailed oversight.” This includes a regulatory environment that is suited to 21st-century challenges rather than to 1970s-era technophobia and nuclear dread.

Whoever does it, and whichever fuel they use, the success of deep decarbonization will hinge on technological progress. Why assume that the know-how of 2018 is the best the world can do? Decarbonization will need breakthroughs not just in nuclear power but on other technological frontiers: batteries to store the intermittent energy from renewables; Internet-like smart grids that distribute electricity from scattered sources to scattered users at scattered times; technologies that electrify and decarbonize industrial processes such as the production of cement, fertilizer, and steel; liquid biofuels for heavy trucks and planes that need dense, portable energy; and methods of capturing and storing CO2.

The 100% Solution provides a framework to reach these economies of scale for carbon-neutral technologies:

We must replace every process or piece of equipment that currently emits greenhouse gases with a process or piece of equipment that achieves the same function but does not emit greenhouse gases. In most cases, the new systems should function in people’s lives in similar ways to the old systems.

In order to fully roll out all new processes or pieces of equipment, most must become cheaper than current systems. We can achieve this through innovation projects, scaling up clean technologies until every carbon-neutral technology is the cheapest and obvious choice for families and companies across the globe.

Manufacturing scale-up is the easiest option to carry out and the most likely to produce significant cost reductions for most processes or pieces of equipment we need. Production subsidies and financing will be needed for certain technologies that can’t be made cheap enough outright, but they shouldn’t be relied on for everything, or countries offering those options would stop being able to afford them. Inventing new technologies (including minor changes to individual components/etc that make a product cheaper) can have dramatic benefits, but is the least certain option, so it can’t be the only option considered for any given process or type of equipment we need.

It will take time to deploy all the necessary infrastructure even after it becomes cheaper than fossil fuel systems, so to achieve global net-negative emissions by 2050, industrialized countries must make most clean systems affordable enough in the next 5-15 years. This speaks to the need for an immediate, massive investment to scale up the industries we need and position them to export equipment worldwide.

Five pillars of action are required to achieve a 100% solution globally:

- Deploy clean electricity generation.

- Electrify equipment that can be electrified.

- Create synthesized carbon-neutral fuels for equipment that can’t be electrified or isn’t electrified by 2050.

- Change various processes to eliminate non-energy emissions (ex: CO2 is currently a byproduct of chemical reactions in cement manufacturing) – especially in agriculture (ex: using crop rotation, cover crops, and enforcement against deforestation to lower emissions from soil and deforestation).

- Make up for the remaining emissions and get to negative emissions using sequestration.

These pillars are a framework, criteria with which we can judge whether specific policy proposals (recent examples include the Evergreen Action Plan, the House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis’ report, the Biden-Sanders unity task force report, and the new Biden campaign climate plan) would fully solve the problem, or in what areas they have gaps. The 100% Solution book gets into more specifics of what types of equipment or policy can or can’t contribute to a full solution within each pillar, but the 100% Solution framework does not lay out a proposed package of specific policies.

Inadequate solutions

The following solutions, while well-intentioned, are ultimately misguided; they are inefficient, ineffective, or both, at reaching acceptable levels of emissions. Thus, they should not be included in practical climate policies.

Small environmental gestures

Individual actions add up to collective behavior, which in turn can make a significant dent in emissions. However, some individual sacrifices simply don’t make much of a difference, and miss the forest for the trees.

Enlightenment Now reminds us to think in scale:

People have trouble thinking in scale: they don’t differentiate among actions that would reduce CO2 emissions by thousands of tons, millions of tons, and billions of tons. Nor do they distinguish among level, rate, acceleration, and higher-order derivatives—between actions that would affect the rate of increase in CO2 emissions, affect the rate of CO2 emissions, affect the level of CO2 in the atmosphere, and affect global temperatures (which will rise even if the level of CO2 remains constant). Only the last of these matters, but if one doesn’t think in scale and in orders of change, one can be satisfied with policies that accomplish nothing.

Much of the public chatter about mitigating climate change involves voluntary sacrifices like recycling, reducing food miles, unplugging chargers, and so on. … But however virtuous these displays may feel, they are a distraction from the gargantuan challenge facing us.

Greatly reducing standard of living

Technological advances since the Industrial Revolution (flying, construction, etc.) are often credited with the onset of climate destruction, yet they’ve brought countless improvements to humanity’s standard of living. Reductions in harmful behaviors are necessary, but completely foregoing them isn’t an option. We must instead make them more efficient, and internalize the damages they cause into their prices.

Enlightenment Now provides an overview of the ecomodernist approach:

But is progress sustainable? A common response to the good news about our health, wealth, and sustenance is that it cannot continue. As we infest the world with our teeming numbers, guzzle the earth’s bounty heedless of its finitude, and foul our nests with pollution and waste, we are hastening an environmental day of reckoning. If overpopulation, resource depletion, and pollution don’t finish us off, then climate change will.

As in the chapter on inequality, I won’t pretend that all the trends are positive or that the problems facing us are minor. But I will present a way of thinking about these problems that differs from the lugubrious conventional wisdom and offers a constructive alternative to the radicalism or fatalism it encourages. The key idea is that environmental problems, like other problems, are solvable, given the right knowledge.

Ecomodernism begins with the realization that some degree of pollution is an inescapable consequence of the Second Law of Thermodynamics. When people use energy to create a zone of structure in their bodies and homes, they must increase entropy elsewhere in the environment in the form of waste, pollution, and other forms of disorder. The human species has always been ingenious at doing this—that’s what differentiates us from other mammals—and it has never lived in harmony with the environment.

A second realization of the ecomodernist movement is that industrialization has been good for humanity. It has fed billions, doubled life spans, slashed extreme poverty, and, by replacing muscle with machinery, made it easier to end slavery, emancipate women, and educate children … It has allowed people to read at night, live where they want, stay warm in winter, see the world, and multiply human contact. Any costs in pollution and habitat loss have to be weighed against these gifts. As the economist Robert Frank has put it, there is an optimal amount of pollution in the environment, just as there is an optimal amount of dirt in your house. Cleaner is better, but not at the expense of everything else in life.

The third premise is that the tradeoff that pits human well-being against environmental damage can be renegotiated by technology. How to enjoy more calories, lumens, BTUs, bits, and miles with less pollution and land is itself a technological problem, and one that the world is increasingly solving.

But for many reasons, it’s time to retire the morality play in which modern humans are a vile race of despoilers and plunderers who will hasten the apocalypse unless they undo the Industrial Revolution, renounce technology, and return to an ascetic harmony with nature. Instead, we can treat environmental protection as a problem to be solved: how can people live safe, comfortable, and stimulating lives with the least possible pollution and loss of natural habitats? Far from licensing complacency, our progress so far at solving this problem emboldens us to strive for more. It also points to the forces that pushed this progress along.

One can, alternatively, daydream that moral suasion is potent enough to induce everyone to make the necessary sacrifices. But while humans do have public sentiments, it’s unwise to let the fate of the planet hinge on the hope that billions of people will simultaneously volunteer to act against their interests. Most important, the sacrifice needed to bring carbon emissions down by half and then to zero is far greater than forgoing jewelry: it would require forgoing electricity, heating, cement, steel, paper, travel, and affordable food and clothing.

100% renewable energy

Often hailed as the savior to the climate crisis, renewable energy sources suffer from drawbacks in intermittency and land-use. While renewables play a key role in decarbonization, they should undergo a cost-benefit analysis within energy policies and be balanced with nuclear power.

Enlightenment Now highlights some of these issues:

A second key to deep decarbonization brings up an inconvenient truth for the traditional Green movement: nuclear power is the world’s most abundant and scalable carbon-free energy source. Although renewable energy sources, particularly solar and wind, have become drastically cheaper, and their share of the world’s energy has more than tripled in the past five years, that share is still a paltry 1.5 percent, and there are limits on how high it can go. The wind is often becalmed, and the sun sets every night and may be clouded over. But people need energy around the clock, rain or shine. Batteries that could store and release large amounts of energy from renewables will help, but ones that could work on the scale of cities are years away. Also, wind and solar sprawl over vast acreage, defying the densification process that is friendliest to the environment. The energy analyst Robert Bryce estimates that simply keeping up with the world’s increase in energy use would require turning an area the size of Germany into wind farms every year. To satisfy the world’s needs with renewables by 2050 would require tiling windmills and solar panels over an area the size of the United States (including Alaska), plus Mexico, Central America, and the inhabited portion of Canada.

Nuclear energy, in contrast, represents the ultimate in density, because, in a nuclear reaction, E = mc2: you get an immense amount of energy (proportional to the speed of light squared) from a small bit of mass. Mining the uranium for nuclear energy leaves a far smaller environmental scar than mining coal, oil, or gas, and the power plants themselves take up about one five-hundredth of the land needed by wind or solar. Nuclear energy is available around the clock, and it can be plugged into power grids that provide concentrated energy where it is needed. It has a lower carbon footprint than solar, hydro, and biomass, and it’s safer than them, too.

Economics for the Common Good advocates an objective approach when analyzing seemingly green energy policies:

In addition to tradable emissions permits and carbon taxes, many countries use a variety of “command and control” approaches (which I will come back to). Some of these measures are too expensive given their limited effectiveness in reducing global warming. While well-meaning, establishing nonquantified environmental standards or requiring public authorities to choose renewable energy sources often leads to a lack of consistency that substantially increases the cost of reducing emissions. States sometimes spend as much as a thousand dollars per ton of carbon avoided (this used to be the case particularly in Germany, a country that does not have a lot of sunshine but installed first-generation solar power systems) when other measures to reduce emissions would cost just ten dollars per ton.

24 Sep 2020

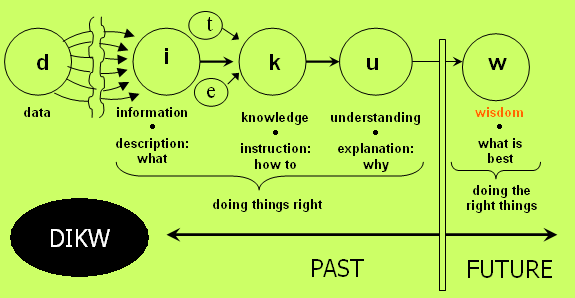

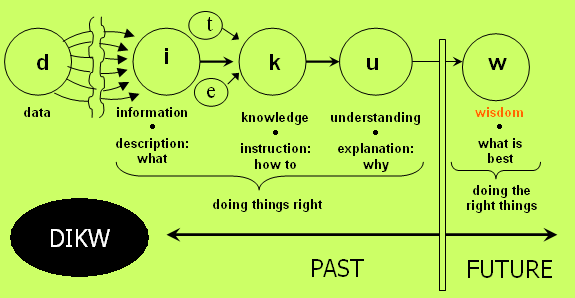

The DIKW model is a conceptual relationship between data, information, knowledge, and wisdom. Several variants of this model exist, which lack consensus on the definition of each term, and the transformations between them.

Russell Ackoff’s 1989 paper From Data to Wisdom is often quoted to define these terms:

Wisdom is located at the top of a hierarchy of types, types of content of the human mind. Descending from wisdom there are understanding, knowledge, information, and, at the bottom, data. Each of these includes the categories that fall below it – for example, there can be no wisdom without knowledge.

Data are symbols that represent properties of objects, events and their environments. They are products of observation. … Information, as noted, is extracted from data by analysis … Data, like metallic ores, are of no value until they are processed into a useable [sic] (i.e. relevant) form. Therefore, the difference between data and information is functional, not structural, but data are usually reduced when they are transformed into information.

Information is contained in descriptions, answers to questions that begin with words such as who, what, where, when, and how many.

Knowledge is know-how, for example, how a system works. It is what makes possible the transformation of information into instructions. It makes control of a system possible. To control a system is to make it work efficiently. … Knowledge can be obtained in two ways: either from transmission by another who has it, by instruction, or by extracting it from experience. In either case, the acquisition of knowledge is learning.

Learning and adaptation may take place by trial and error or systematically by detection of error and its correction. Diagnosis is the identification of the cause of error and prescription is instruction directed at its correction. Systematic learning and adaptation require understanding error, knowing why it was made and how to correct it.

Information, like news, ages relatively rapidly. Knowledge has a longer lifespan, although inevitably it too becomes obsolete. Understanding has an aura of permanence around it. Wisdom, unless lost, is permanent …

… information, knowledge and understanding all focus on efficiency. Wisdom adds value, which requires the mental function we call judgement. Evaluations of efficiency all are based on a logic which, in principle, can be specified, and therefore can be programmed and automated. These principles are general and impersonal. We can speak of the efficiency of an act independent of the actor. Not so for judgment. The value of an act is never independent of the actor, and seldom is the same for two actors even when they act in the same way. Efficiency is inferrable [sic] from appropriate grounds; ethical and aesthetic values are not. They are unique and personal.

The DIKW model is summarized in the following flowchart (from Wikipedia):

[T & E meaning tacit and explicit]

Gene Bellinger et al. present an alternative view:

Personally I contend that the sequence is a bit less involved than described by Ackoff. The following diagram represents the transitions from data, to information, to knowledge, and finally to wisdom, and it is understanding that support [sic] the transition from each stage to the next. Understanding is not a separate level of its own.

The DIKW model has its limitations; it isn’t universally applicable, and can break down when analyzing the semantic definitions of each step (e.g. drawing the line between data and information). Though I find the model is still a useful concept, which illustrates:

- the “graduation” of data, information, and knowledge (however you want to define them) into increasingly simplified but useful forms

- the relationship between stages of the DIKW pyramid and timelessness

- the difference between operational efficiency (doing things right), and directional effectiveness (doing the right things)

- doing the right thing requires knowing how the system currently works

- how the value of an act differs between individuals

09 Aug 2020

The complexity and nuance across the interconnected domains of knowledge in the world make it challenging to progress on social issues. For example, an environmentalist’s goals are connected with environmental science, engineering, manufacturing, economics, and politics, among others. How well should one try to understand these interconnected domains to progress on their goals?

The general consensus is it depends on one’s strengths, which is echoed by:

Scott Page

From The Knowledge Project:

One of the things I talk about in both The Diversity Bonus and also in The Model Thinker is that you can think of yourself as this toolbox and you’ve got some capacity to accumulate tools, mental models, ways of thinking. What you could decide to do is you could decide to go really deep. You could be the world’s expert, or one of the world’s experts, on random forest models or goals or the Lyapunov functions. You could be one of the world’s leading practitioners of signaling models in economics. Alternatively, what you could do is you could go deep on a handful of models, where there could be three or four things you’re pretty good at. Or you could be someone who I think … a lot of people are really successful … by having just an awareness of a whole bunch of models. Having 20 models that you have at your disposal that you can think about. Then when you realize this one may be important, then you dig a little bit deeper.

The world is a complex place. I think that the challenge is to become a more nimble thinker, is to be able to move across these models. But at the same time, if you can’t, if that’s just not your style, that doesn’t mean there’s no place for you in the modern economy. To the contrary, it means that maybe you should be one of those people who goes deep.

The point of the core philosophy of The Model Thinker is even if you do the best you can, even if you’re a lifelong learner, even if you’re constantly amassing models, you’re still not going to be up to the task of solving any one … you yourself are not going to solve the obesity epidemic. You yourself are not going to create world peace. You yourself are not going to solve climate issues. Your brain just isn’t going to be big enough. But collections of people by having different ensembles of models, creating a larger ensemble of models actually have a hope of addressing these problems.

You need this weird balance of specialist, super-generalist, quasi-specialist, generalist. There’s even people who I’ve heard

describe … that their human capital is in the shape of a T, in the sense that there’s a whole bunch of things they know a decent amount about and then one thing they know deep. Where other people describe themselves as a symbol for pi where there’s two things they know pretty deep, not as deep as the T person, and then a range of things that connect those two areas of knowledge, and then a little bit out to each side. I think that it’s worth having a discussion

with yourself … is to think okay, what are my capacities? Am I someone who is able to learn things really, really deeply? Am I able to learn a lot of stuff? Then think about a strategy for what sort of human capital you develop.

Because I think you can’t make a difference in the world, you can’t go out there and do good, you can’t take this knowledge and this wisdom and make the world a better place unless you’ve acquired a set of useful tools, not only individually, but also they’ve got to be collectively useful. Because you could learn 15 different models that are disconnected, that apply to different cases, and never have any sort of gestalt, any sort of whole, and that might make it hard for you to make a contribution. Or you could say, I’m going to be someone who learns 30 different models. But if you’re not someone who is nimble and able to move across them, that may be more frustrating for you.

In a complex world, your ability to succeed is going to depend on you filling a niche that’s valuable, which as in Barabasi’s book, it could be connecting things, it could be pulling resources and ideas from different places, but it’s going to be filling a niche and that niche could take all sorts of different forms.

Atul Gawande

From The Knowledge Project:

I majored in biology, but I also majored in political science, kind of looking for… there must be more to the world than just medicine. And I found it. I found it in lots and lots of different places. Some in science; I worked in a lab. Some—you know, I tried everything in college. I was in a band, I learned to play guitar, I wrote music reviews for the student newspaper. I joined Amnesty International. I worked on Gary Hart’s very shortlived campaign for president as a volunteer. Then, when I got out of Stanford I went on to do a master’s degree in politics and philosophy of economics at Oxford, out of hope that I could maybe do a graduate degree in political theory or something like that. I just found out I wasn’t very good at those questions and a lot of the things that I tried I just wasn’t really made for or cut out for. And I kept coming back to medicine as a place where I was familiar, I was comfortable. It wasn’t for the best reasons, right? It was a place that I knew and I could thrive.

What I also liked about it was, you didn’t actually have to decide what you wanted to be when you grew up. It deferred all kinds of decisions while I figured out everything else along the way. So when I got out of graduate school and decided to just stop with a master’s degree in philosophy… then I worked actually in politics for a couple of years on the Hill and found I didn’t want to just work in politics.

I kept finding myself gravitating back to medicine where you could have skill… the values were at the core of it for me, that it was about grappling with how science meets humanity in a place where—and policy and the world and all the complexities of life—in a place where you could really think about the individual in front of you, but also the system as a whole, and I wanted to somehow connect on both levels.

I like having a lot of irons in the fire. I like being a jack of all trades. Finding the edges between things is often where I have something to add. You know, if you look at what I contribute in these spaces, it’s not genius ideas. A checklist for surgery, it’s just taking an idea from one domain and saying let’s bring it over to the other and see if it can work, or understanding what people’s goals are when they face mortality and end of life. A lot of them just come from digging in deep enough to understand the gap between what we’re aspiring for and the reality of what we’re doing, and then trying to figure out where the bridge is to a narrow that wide gap.

I think I grew up kind of interested in how the world worked, and I had a very limited vantage point in my town in Ohio growing up. And every opportunity to see more, my handle hold, was through science. My parents were doctors and that gave me a way of seeing and thinking about the world, but then my parents were also people who were deeply involved in the community and trying to deal with the challenges in a community that had a college, but was also the poorest county in Ohio. My brain worked in such a way that, I loved understanding the ideas at an ideas level and then trying to figure out how you ground it. So I was always looking for ways to understand the world, and that meant needing to bridge and look more widely. And so each move, college and then going beyond, kept widening that, and I’ve just loved that. I’ve loved adding another space that I could explore and it was only by happenstance, it was very late that I found I had anything to contribute. That really wasn’t until my thirties when I finally found I could connect the dots between different things I had been learning about.

Charlie Munger

From the 2016 Daily Journal Annual General Meeting, on whether he is in favor of specialization or taking a synthesis/multi-disciplinary approach:

Saying one is in favor of synthesis is like saying one is in favor of reality. It is easy to say we want to be good at it, but the rewards system pays for extreme specialization. You are usually way better off being a deep expert [in one thing] than someone an inch deep in a lot of disciplines. It [synthesis] is helpful to some but not the best career advice for most people. The trouble is you make terrible mistakes everywhere else without it, so synthesis should be a second attack on the world after specialization. It is defensive, and it helps one to not be blindsided by the rest of world.

From the 2017 Daily Journal Annual General Meeting:

I don’t think operating over many disciplines as I do is a good idea for most people. I think it’s fun, that’s why I’ve done it. I’m better at it than most people would be. And I don’t think I’m good at being the very best for handling differential equations. So it’s in a wonderful path for me, but I think the correct path for everybody else is to specialize and get very good at something that society rewards and get very efficient at doing it. But even if you do that, I think you should spend 10 or 20% of your time into trying to know all the big ideas in all the other disciplines. Otherwise… I use the same phrase over and over again… otherwise you’re like a one legged man in an ass-kicking contest. It’s just not going to work very well. You have to know the big ideas in all the disciplines to be safe if you have a life lived outside a cave. But no, I think you don’t want to neglect your business as a dentist to think great thoughts about Proust.

Tyler Cowen

From The Knowledge Project, on Munger’s thoughts on specialization from the 2017 Daily Journal Annual General Meeting:

I mean maybe most people, but you know it’s person by person and for some people it should be 50–50. Certainly at the higher levels I think generalists are important. If you look at CEOs several decades ago, most CEOs were people hired from within that sector and now a CEO is much more often hired across sectors. So someone who, you know, worked for an oil company would then be hired to run a manufacturing firm. So that’s showing some kinds of knowledge are actually more general.

If you think, well, insiders have some kind of natural advantage in having, you know, an inside track, if companies are more willing to hire these outsiders, I think that’s a clear sign that executive knowledge is becoming more general in nature, more global, more a set of skills about communicating, understanding how politics, global economy, internal management all tie together. Those are somewhat general skills. You do need to understand something about your sector too, though.