15 Mar 2020

Summary

From Encyclopedia Britannica:

Political scientists have been less concerned with what part public opinion should play in a democratic polity and have given more attention to establishing what part it does play in actuality. From the examination of numerous histories of policy formation, it is clear that no sweeping generalization can be made that will hold in all cases. The role of public opinion varies from issue to issue, just as public opinion asserts itself differently from one democracy to another. Perhaps the safest generalization that can be made is that public opinion does not influence the details of most government policies but it does set limits within which policy makers must operate. That is, public officials will usually seek to satisfy a widespread demand—or at least take it into account in their deliberations—and they will usually try to avoid decisions that they believe will be widely unpopular.

Context

The extent of public opinion’s influence within the US government is described in American Government 2e:

Individually, of course, politicians cannot predict what will happen in the future or who will oppose them in the next few elections. They can look to see where the public is in agreement as a body. If public mood changes, the politicians may change positions to match the public mood. The more savvy politicians look carefully to recognize when shifts occur. When the public is more or less liberal, the politicians may make slight adjustments to their behavior to match. Politicians who frequently seek to win office, like House members, will pay attention to the long- and short-term changes in opinion. By doing this, they will be less likely to lose on Election Day. Presidents and justices, on the other hand, present a more complex picture.

Overall, it appears that presidents try to move public opinion towards personal positions rather than moving themselves towards the public’s opinion. If presidents have enough public support, they use their level of public approval indirectly as a way to get their agenda passed.

… one study [on the House of Representatives], by James Stimson, found that the public mood does not directly affect elections, and shifts in public opinion do not predict whether a House member will win or lose. These elections are affected by the president on the ticket, presidential popularity (or lack thereof) during a midterm election, and the perks of incumbency, such as name recognition and media coverage. In fact, a later study confirmed that the incumbency effect is highly predictive of a win, and public opinion is not. In spite of this, we still see policy shifts in Congress, often matching the policy preferences of the public. … The study’s authors hypothesize that House members alter their votes to match the public mood, perhaps in an effort to strengthen their electoral chances.

The Senate is quite different from the House. Senators do not enjoy the same benefits of incumbency, and they win reelection at lower rates than House members. Yet, they do have one advantage over their colleagues in the House: Senators hold six-year terms, which gives them time to engage in fence-mending to repair the damage from unpopular decisions. In the Senate, Stimson’s study confirmed that opinion affects a senator’s chances at reelection, even though it did not affect House members. Specifically, the study shows that when public opinion shifts, fewer senators win reelection. Thus, when the public as a whole becomes more or less liberal, new senators are elected. Rather than the senators shifting their policy preferences and voting differently, it is the new senators who change the policy direction of the Senate.

There is some disagreement about whether the Supreme Court follows public opinion or shapes it. The lifetime tenure the justices enjoy was designed to remove everyday politics from their decisions, protect them from swings in political partisanship, and allow them to choose whether and when to listen to public opinion. More often than not, the public is unaware of the Supreme Court’s decisions and opinions. … But do the justices pay attention to the polls when they make decisions? … Studies that look at the connection between the Supreme Court and public opinion are contradictory. … Overall, however, it is clear that public opinion has a less powerful effect on the courts than on the other branches and on politicians. Perhaps this is due to the lack of elections or justices’ lifetime tenure, or perhaps we have not determined the best way to measure the effects of public opinion on the Court.

This dynamic is reinforced in Interest Groups and Lobbying, which illustrates how public opinion impacts the success of social movements and interest groups in making policy changes:

Movements also need opportunities to succeed. It is romantic to think that movements create their own opportunities through passionate protests, but protests more often capitalize and expand on already existing opportunities than create new ones. Usually such political opportunities arise when the interests of the aggrieved group may be convincingly portrayed as consistent with dominant social values. As noted earlier, the United States goes through cycles in which an emphasis on collective morality as the legitimate basis for lawmaking is displaced by economic individualism (McFarland 1991). Then, when the pendulum swings too far in that direction, interest in the collective good reasserts itself. If current policy treats a social group harshly during times of stability, it is presumed that they brought it on themselves, and nothing is done to help them. But when new values begin reshaping public policy, there may be an opportunity for marginalized interests to link their grievances to now important social values and gain public sympathy. Radical ideas start to have the ring of truth, and would-be leaders of the oppressed group see that an opportunity has arisen and the time is right to demand justice (Meyer 1993, 455; Tilly 1978).

The issues that members of Congress are concerned with, and how they should be resolved, are largely determined by the policy positions that please their “reelection constituency”, meaning the voters who voted for them in the past and hopefully will do so again (Fenno 1978). Lobbyists need legislators to influence policy in Congress, so lobbyists must persuade legislators that what group members want is more or less consistent with what their reelection constituencies want.

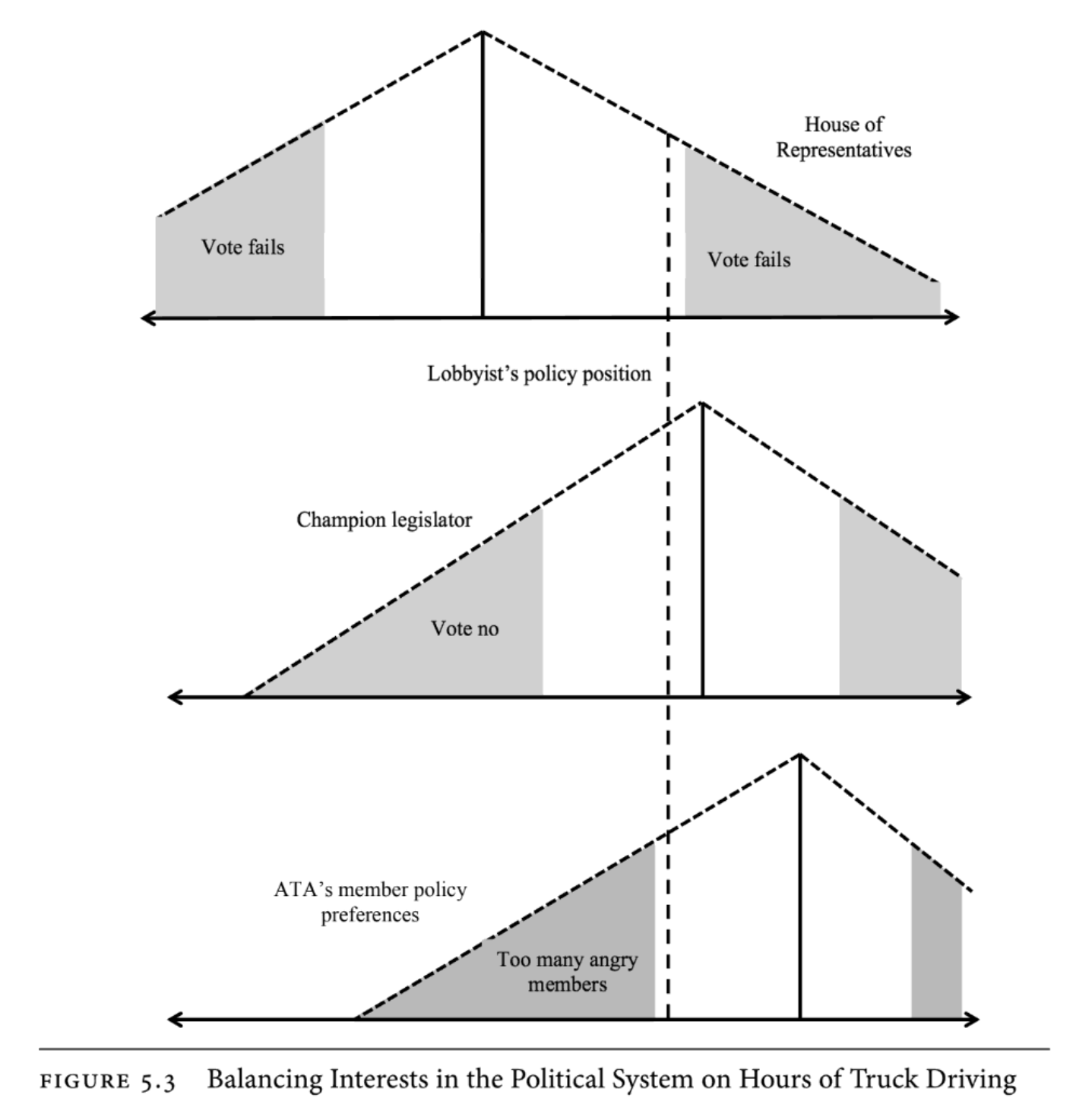

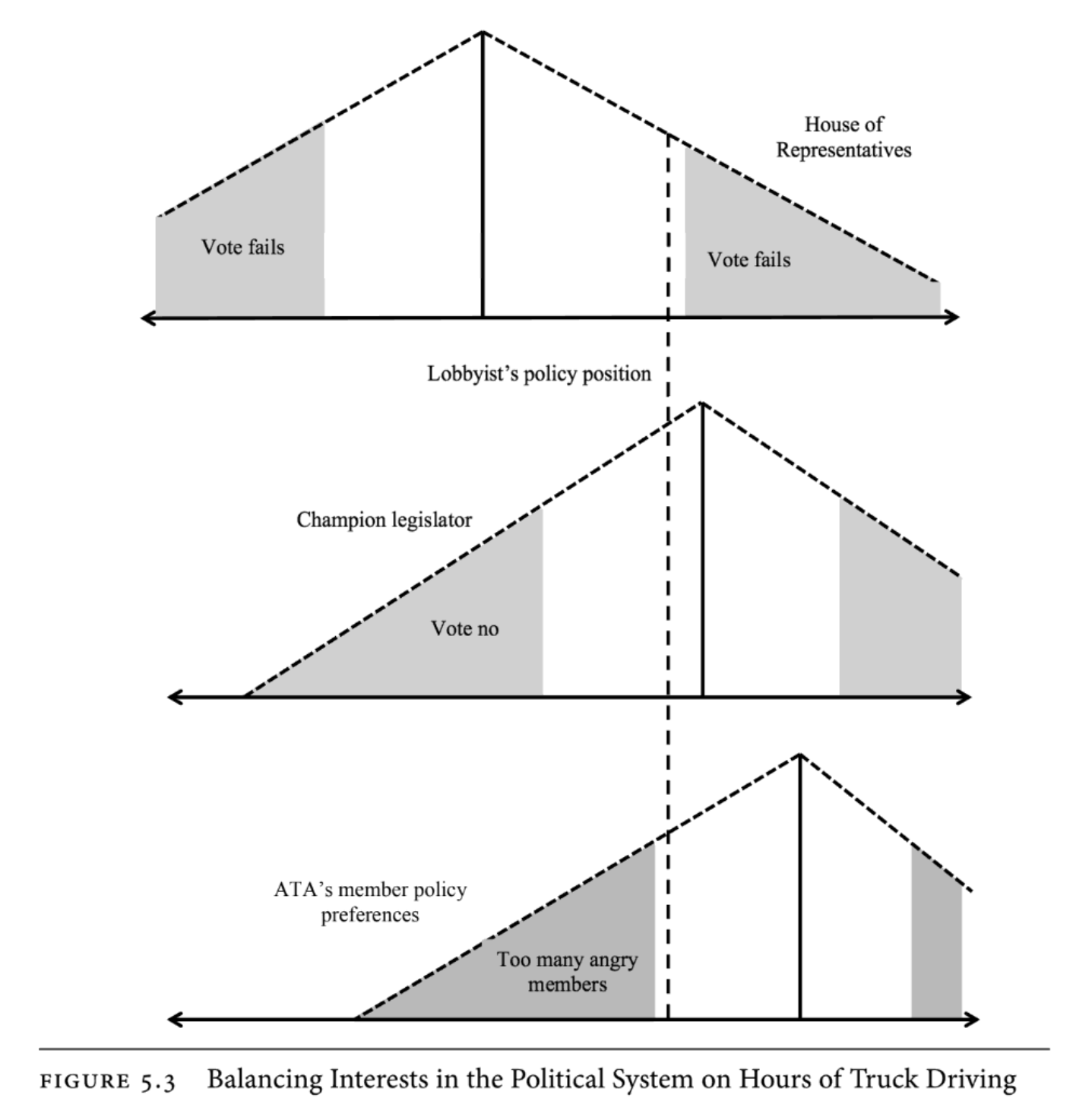

The vertical black line [in the “Champion legislator” section] shows that the legislator prefers a less restrictive policy when it comes to determining hours a trucker can drive. Perhaps the legislator is from a state where trucking is a major employer and he or she wants more industry support in the next election. Although the legislator is somewhat flexible about the ideal policy (is eight hours that different from seven and a half?), there are limits, shown by the tentlike dashed lines and gray areas in the … graph. He or she will not support a driving hours policy in the gray “vote no” zone. The white area around the legislator’s preferred policy, however, represents the other proposals he or she could be persuaded by the ATA to support in exchange for votes in the next election. Take the proposal represented by the dashed vertical line. It is not ideally supported by most ATA members, nor is it the legislator’s ideal solution, but it is close enough to the solid vertical lines for the legislator to support it and still expect to have the votes of a plurality, perhaps even a majority, of truckers.

So the ATA lobbyist can advocate for a compromise everyone can live with. The dashed line connecting group members to the legislator … represents this policy compromise on the driving hours issue. It is still … in the main bubble of group member preferences and also not in the legislator’s “vote no” zone. The legislator can comfortably support this policy, and many—perhaps most—group members will also support it. Almost everyone more or less gets what they want. The legislator will push for the policy in Congress, which means the lobbyist’s goal has been achieved, and his or her career remains in good shape.

What about the rest of Congress? One legislator may be all a lobbyist needs to get a policy proposal introduced in Congress, whether as a new bill or an amendment to an existing bill, but it does not get the job done. No one is an island when it comes to making policy, whether it is a new statute, a new judicial precedent, or a new administrative rule. Both houses of Congress need majorities to move policies out of committee and through the parent chamber, with sixty plus votes often needed in the Senate to overcome a filibuster. Presidential executive orders and agency rules can be overridden by legislative statute or sometimes influenced by Congress (McCubbins and Schwartz 1984; Balla 1998); federal judicial decisions may be overturned by statute; and statutes, rules, executive orders, and lower court decisions can all be struck down by the Supreme Court as unconstitutional. It is a lawmaking system with many parts, and no lobbyist dares to forget it.

This means moving beyond a simple alignment of group member interests with the interests of one lawmaker. To keep this simple I focus here on just the US House of Representatives. The House operates under straight majority rule, meaning a majority of representatives must be willing to vote for whatever policy is preferred by ATA members and the legislator … . Since the lobbyist and legislator want the new policy enacted, they must choose [a] position on the number of driving hours, one that they think can pass the House. Yet the lobbyist, and to some extent the reelection-minded legislator, must still keep an eye on what group members will accept, making the balancing act even more precarious.

In the bottom graph … , I [formulate] the distribution of ATA member preferences over the driving hours continuum so that the tentlike shape is a combination of all members’ ideal positions and intensity of their feelings. If members were more united in their preferences for policy outcomes, and/or felt more strongly about this issue, then more members would leave the group the further the lobbyist’s official position was from the solid vertical line—and the dashed tented lines would have steeper slopes. At the top … is a similar graph for the members of the House. Some care about trucking policy, while others couldn’t care less, but the white space under the peak indicates the policy positions that would garner a majority of votes in the House. The vertical solid black line marks the position that would attract the most votes.

The lobbyist and the champion legislator know where the House collectively stands on the driving hours issue and what positions can win a majority. The policy acceptable to the most legislators and group members is marked by the dashed line running through all three parts … . It is not what the champion legislator would ideally prefer, and it is not likely to gain anything more than a bare majority of votes in the House. It can just barely be sold by the lobbyist to enough ATA members to keep the group viable because it is fairly restrictive in the number of allowable driving hours. But for most group members and legislators it is better than nothing, and nothing would have been the result if the lobbyist had pushed a position that more ATA members would support, or one more ideally suited to the champion legislator’s goals. That was impossible, so the lobbyist skillfully balances all of the competing pressures he or she is under, satisfying the demands of all eight assumptions, to produce a policy that at least passes the House and pleases more trucking companies than it angers. Lobbying is not only the art of persuasion; it is the science of the possible, though there is an art to making the possible look desirable.

There are several points to take away from this model. First, it provides insight into the real job of lobbyists. Lobbyists are sellers: people whose job it is to convince others, such as their members and the lawmakers controlling the levers of power, that achieving a policy outcome is in their interests. Second, it shows that lobbying is about compromise. Lobbyists must convince all parties involved to accept an outcome that is less than ideal because their individual preferences are impossible to achieve given the current disposition of everyone else in the political system. Lobbyists have difficult jobs trying to balance these competing interests, finding the one position that enough people—group members, champion legislators, and other legislators—can all agree to and arriving at the best policy they can get. The lobbyist only needs to avoid picking a position that alienates too many of his or her members (the shaded region of the lower [graph]). Lobbyists may, however, use their control of information to convince members that the policy compromise getting enacted into law is actually better than what members originally wanted. And this simple model fails to include senators, the president, the bureaucracy, other interest groups, and possibly the courts. It is not easy being a successful lobbyist!

Lastly, the ATA lobbyist also targeted a legislator who more or less already agreed with the position many ATA members wanted. This is important to understand. A well-known study in 1963 about lobbying on American trade policy revealed for the first time something that cuts against popular perceptions of lobbyists: lobbyists tend to lobby their allies, those lawmakers already supporting them, not their enemies (Bauer, Pool, and Dexter 1963). This model shows why. To get their jobs done, lobbyists must lobby their friends, legislators whose positions are relatively close to those of many group members.

15 Mar 2020

Summary

Since American society is so heterogeneous with many groups organized, or at least with the potential to be organized, around a wide range of issues and beliefs, there is no way they can [all] be represented [well] by any political party. … This is the potential of interest groups–they can and do provide focused representation for small groups of people organized around narrow, well-defined interests that could probably not ever be priorities for political parties.

The downside, though, is that there are so many private organizations representing group interests in national politics today that the relatively small number of public officials whose attention they compete for cannot possibly respond to them all. Nor do interest groups represent all factions of the public equally. Some have more resources than others with which they can make their constituent members’ voices heard more loudly by lawmakers.

… interest groups are considered legitimate because we believe the pursuit of self-interest is close to sacred. It probably could not be any other way in an economic system that assumes the best result for society comes when people compete with each other to satisfy their self-interest. … Barring such an unlikely change [of economic system], it may be best to think more about how we can use interest groups and their adversarial impulse–which itself is just a reflection of our own adversarial nature–to achieve the greatest good for the greatest number of people.

Context

From Interest Groups and Lobbying:

- Interest groups are collections of people with essentially the same self-interest, about which they feel so strongly that they collectively form an organization to promote and defend it through the political process.

- The development of the political philosophy of the social contract underlying our civilization prioritizes individual self-interest and protects the pursuit of that self-interest through politics.

The First Amendment’s last clause reads: “Congress shall make no law … abridging … the right of the people to freely assemble and petition government for a redress of grievances”. It captures the two key parts of interest group politics: collective action (the right to freely assemble) and lobbying government to answer the demands of citizens (petition for redress of grievances). The idea of citizens with similar interests proactively or reactively demanding that their government protect their self-interest is the cornerstone of democratic government, and using intermediaries to press these demands is the very definition of representation.

Since American society is so heterogeneous with many groups organized, or at least with the potential to be organized, around a wide range of issues and beliefs, there is no way they can be represented by any political party. To win majorities, parties must assemble and represent many interests, but trying to represent everybody means they represent nobody well. US presidents and senators have the same problem. Even House members often represent too many competing interests in their districts to be effective advocates for them all. Private organizations speaking for distinct groups of people have no need to represent any majority.

This is the potential of interest groups–they can and do provide focused representation for small groups of people organized around narrow, well-defined interests that could probably not ever be priorities for political parties. The downside, though, is that there are so many private organizations representing group interests in national politics today that the relatively small number of public officials whose attention they compete for cannot possibly respond to them all. Nor do interest groups represent all factions of the public equally. Some have more resources than others with which they can make their constituent members’ voices heard more loudly by lawmakers. And some potential constituent-members simply cannot get organized, or even realize that they had better be organized, if they want to avoid being hurt by the policies advanced by competing interest groups. What groups do share with parties and constituent-based representation in government is a disregard for the public interest.

… interest groups are considered legitimate because we believe the pursuit of self-interest is close to sacred. It probably could not be any other way in an economic system that assumes the best result for society comes when people compete with each other to satisfy their self-interest. As Jane Mansbridge observed, democratic politics in a free-market economy are usually adversarial, and this leaves no room for thinking about the common good. Indeed, there may be no common good or public interest in such a system. If we wished to eliminate interest groups and lobbying, as Madison understood, we would have to fundamentally rethink who we are and what rights and liberties we expect to enjoy in our political system. Barring such an unlikely change, it may be best to think more about how we can use interest groups and their adversarial impulse–which itself is just a reflection of our own adversarial nature–to achieve the greatest good for the greatest number of people.

15 Mar 2020

Summary

Group members have interests that manifest in how they want to see an issue, like how many hours a trucker can drive, resolved with public policy. But group members vary in just what they think these policy solutions should be, just as they feel more intensely about some issues than others and will be less tolerant of anything that falls short of what they consider an ideal solution. Policy makers also have interests that manifest as ideal solutions to issues, solutions that help them achieve their goals. But there is no reason to believe that members and policy makers all prefer exactly the same policy solutions, or anything even close. Lobbyists may also have personal opinions on how issues should be solved, but that is irrelevant. Never forget about Assumption 1: a lobbyist’s job is to make sure policymaker and group member interests align, or at least appear aligned, or his or her career may be in jeopardy.

Context

From Interest Groups and Lobbying:

… this model will show how lobbyists make decisions based on the motivations of policy members, group members, and their own ambitions. It should help answer the question … about how lobbyists balance competing group member and lawmaker pressures. It should also give some insight into lobbyists’ capacity to meaningfully represent citizen interests before government.

… understanding interest group politics means seeing lobbyists as distinct from the people they represent, even as they pursue these people’s interests … . This is not a pedantic distinction. Senators may act in ways inconsistent with the wishes of their constituents because they have to cope with demands from House members, presidents, bureaucrats, and other senators. So too with lobbyists. Indeed, it may be easier for lobbyists to be swayed by influences other than their own members because, unlike legislators, they do not have to publicly present themselves for validation or rejection in elections.

Assumption 1: Lobbyists want to advance their careers by building and maintaining personal relationships with government officials and by successfully representing member interests.

Like everyone, lobbyists have an interest they strive for; it is just that their interest may not be the same as the interests of the people they represent. They certainly have a professional interest in helping the people they are currently employed to represent, but when the needs of members clash with a lobbyist’s need to maintain good relations with lawmakers, members sometimes fail to come first. Lobbyists believe in Shakespeare’s line “To thy own self be true.”

Assumption 2: Interest group members differ in how they would ideally like to see issues important to them resolved with public policy.

Assumption 3: Some issues are more important to members than others, and they will be more likely to be angry if their ideal positions on these issues are not precisely advocated by their lobbyist.

Assumption 4: Interest group members can quit their organization and are more likely to do so the more dissatisfied they are with the choices of its lobbyist.

… In discussing the internal workings of political groups, economist Albert Hirschman (1970) made a simple but important point. When faced with a leadership that does not appear to have their best interests at heart, members may do one of three things. They may loyally support the group anyway out of regard for the good of the whole, they may try to change the group by pushing out the unresponsive lobbyists and staff, or they may just quit the group entirely and take their dues with them as they exit. Except for some unions and a few professional organizations like bar associations, interest groups do not have compulsory membership. Members may quit at any time.

Assumption 5: Lobbyists have limited resources for pursuing member interest advocacy.

Even when members are happy and pay their dues, there is another crucial limit on what lobbyists can do: money. Members only have so much money to give for group support. … most [group budgets] are not all that large, even when they are supplemented by philanthropies, foundations, wealthy individuals, and the government. The costs of mounting major advocacy campaigns can be enormous, and apart from advocacy, groups also must allocate significant parts of their budgets to the nonpolitical activities and other benefits that members demand (and that may be more important to some members than the advocacy).

Assumption 6: Only elected and appointed government officials may directly influence the government’s policy-making process.

Assumption 7: All government officials seek to achieve professional and policy goals.

Since policy maker support is critical to successful advocacy, lobbyists must find ways to persuade and pressure policy makers into acting on their members’ behalf. … whether by enticements or threats, lobbyists make arguments that are meaningful to policy makers, arguments that convince them that it is in their interests to support a policy proposal that also happens to more or less be what the lobbyist’s members want. Lobbying is the art of pursuing member interests by persuading lawmakers that their interests and member interests are one and the same.

Lobbyists start by understanding what the interests of government officials are. Members of Congress want to be reelected, or to become a senator, governor, or even president (Mayhew 1974). Many also want to make policy consistent with their own ideological beliefs, usually so they have an achievement to advertise when they run for reelection or for election to higher office (Dodd 1977). Appointed officials running administrative agencies that implement the laws Congress passes want larger budgets and less congressional oversight (Downs 1967; Balla 1998). Federal judges, and especially members of the US Supreme Court, with lifetime appointments and largely insulated from political pressures, simply want to advance their ideas of how the Constitution ought to be interpreted and how to make existing law consistent with that ideal (Segal and Spaeth 2002). Is this overly simplistic? Yes. Does this cynically rule out any notion of altruism or a desire to serve the public good? Certainly. But what this stripped-down view of policy maker motivation does provide is stated in the seventh assumption …

See also: Role of Public Opinion in Policy Making.

09 Aug 2019

From Enlightenment Now:

The Second Law of Thermodynamics states that in an isolated system (one that is not taking in energy), entropy never decreases. (The First Law is that energy is conserved; the Third, that a temperature of absolute zero is unreachable.) Closed systems inexorably become less structured, less organized, less able to accomplish interesting and useful outcomes, until they slide into an equilibrium of gray, tepid, homogeneous monotony and stay there.

In its original formulation the Second Law referred to the process in which usable energy in the form of a difference in temperature between two bodies is inevitably dissipated as heat flows from the warmer to the cooler body. … A cup of coffee, unless it is placed on a plugged-in hot plate, will cool down. When the coal feeding a steam engine is used up, the cooled-off steam on one side of the piston can no longer budge it because the warmed-up steam and air on the other side are pushing back just as hard.

How is entropy relevant to human affairs? Life and happiness depend on an infinitesimal sliver of orderly arrangements of matter amid the astronomical number of possibilities. Our bodies are improbable assemblies of molecules, and they maintain that order with the help of other improbabilities: the few substances that can nourish us, the few materials in the few shapes that can clothe us, shelter us, and move things around to our liking. Far more of the arrangements of matter found on Earth are of no worldly use to us, so when things change without a human agent directing the change, they are likely to change for the worse. The Law of Entropy is widely acknowledged in everyday life in sayings such as “Things fall apart,” “Rust never sleeps,” “Shit happens,” “Whatever can go wrong will go wrong,” and (from the Texas lawmaker Sam Rayburn) “Any jackass can kick down a barn, but it takes a carpenter to build one.”

Why the awe for the Second Law? From an Olympian vantage point, it defines the fate of the universe and the ultimate purpose of life, mind, and human striving: to deploy energy and knowledge to fight back the tide of entropy and carve out refuges of beneficial order.

… misfortune may be no one’s fault. A major breakthrough of the Scientific Revolution—perhaps its biggest breakthrough—was to refute the intuition that the universe is saturated with purpose. In this primitive but ubiquitous understanding, everything happens for a reason, so when bad things happen—accidents, disease, famine, poverty—some agent must have wanted them to happen. … Galileo, Newton, and Laplace replaced this cosmic morality play with a clockwork universe in which events are caused by conditions in the present, not goals for the future. People have goals, of course, but projecting goals onto the workings of nature is an illusion. Things can happen without anyone taking into account their effects on human happiness.

02 Jun 2018

Simple definition from Wikipedia:

A proximate cause is an event which is closest to, or immediately responsible for causing, some observed result. This exists in contrast to a higher-level ultimate cause (or distal cause) which is usually thought of as the “real” reason something occurred. In most situations, an ultimate cause may itself be a proximate cause for a further ultimate cause.

Example from Guns, Germs, and Steel:

Yet another type of explanation lists the immediate factors that enabled Europeans to kill or conquer other peoples—especially European guns, infectious diseases, steel tools, and manufactured products. Such an explanation is on the right track, as those factors demonstrably were directly responsible for European conquests. However, this hypothesis is incomplete, because it still offers only a proximate (first-stage) explanation identifying immediate causes. It invites a search for ultimate causes: why were Europeans, rather than Africans or Native Americans, the ones to end up with guns, the nastiest germs, and steel?

Farnam Street goes into further detail by describing techniques for establishing and mapping ultimate causes.