What Causes Generous Behavior?

04 Jun 2023Summary

What causes people to behave in ways that are intended to benefit others (or society as a whole)? These behaviors include a wide variety of activities (from e.g. obeying rules and conforming to socially acceptable behavior, to donating, volunteering, helping, and treating others with kindness), and are important for individual and societal flourishing. One’s life experience can push them towards generous behavior, or antisocial behavior on the other hand, which begs the question of the causes behind generous behavior so it can be realized.

The causes of generosity are complex and multiple, and there is no single explanation for why people act generously. Most research focuses on correlation rather than causation, though The Science of Generosity provides an overview of known causal factors:

- “Blank slate” factors (without having been shaped by life experience):

- Biological (psychological reward - makes us feel good)

- Children appear to have an innate drive to help others, which is later shaped by their life experience

- Individual factors:

- Feelings of empathy, compassion, and other emotions

- Certain personality traits, such as humility and agreeableness

- Values, morals, and sense of identity

- Social and cultural factors:

- Expectation of reciprocation or that their generosity will help their reputation

- Cultural standards of fairness

- Strong social networks

- Other factors that are more nuanced and varied:

- Socioeconomic status

- People are more likely to help a specific person than an abstract or anonymous individual

- People are more likely to help individuals than groups

- Geographic factors (e.g. regional level of trust, city size, diversity)

- Governmental factors (e.g. crowding out individual donations, presence of strong institutions)

- Parenting practices (role-modeling and discussing generosity)

- Prosocial messages in media

- Timing or setting of request

What is generous behavior?

Several terms are used to describe behaviors that benefit others, including “prosocial”, “generous”, and “altruistic”, each with varying implications for the intent and ultimate outcomes of the behavior. Generally, “prosocial” or “generous” refer to behavior that benefits others, but can also benefit the self; whereas “altruistic” behaviors have a purely unselfish interest in helping others. There is debate on whether truly altruistic behavior exists, due to expectations of reciprocity or derived feelings of pleasure. This post focuses on the broader “generous” definition for simplicity.

The Science of Generosity: Causes, Manifestations, and Consequences describes the ways generosity can manifest:

In the Science of Generosity Initiative, as well as in other scholarship, scholars conceive of generosity as including a broad range of activities, such as financial donations to charitable causes, volunteering, taking political action, donating blood and organs, and informal helping. This definition includes the giving of money, possessions, bodily materials, time, or talent in the form of formal volunteering, assistance in the form of informal helping, attention and affection in the form of relational generosity, compassion and empathy, and many other activities that are intended to enhance the wellbeing of others, beyond the self. Many of these activities occur through organizations, such as nonprofit organizations with tax-exempt status. However, the activities need not occur through organizations and can occur instead through interpersonal, group, and other collective interactions. People can also be relationally generous to one another [being “generous with one’s attention and emotions in relationships with other people”].

The Science of Generosity: Causes, Manifestations, and Consequences

The Science of Generosity: Causes, Manifestations, and Consequences confirms the findings of (the similarly-named) The Science of Generosity whitepaper, and adds depth to its conclusions.

Summary

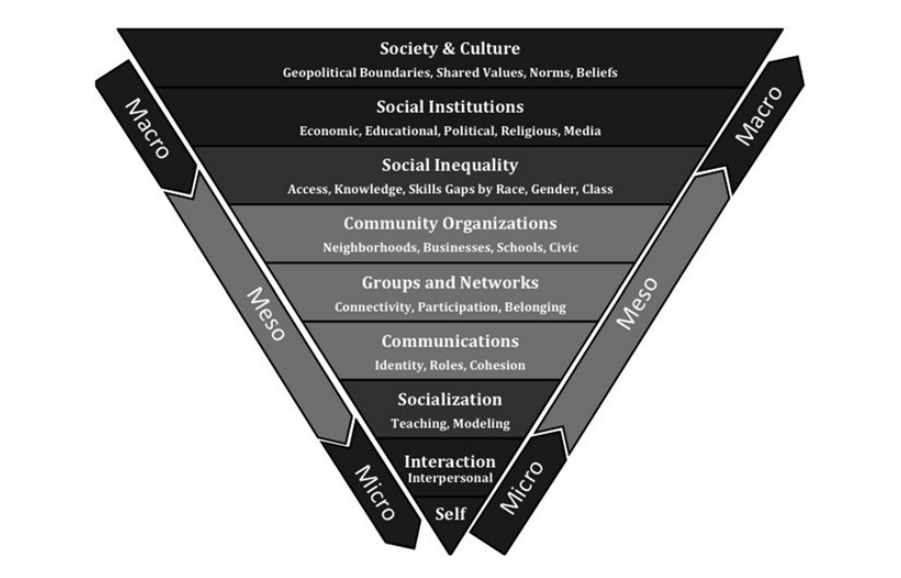

In summary, there are multiple causes of generosity, which can be categorized according to levels of social forces, in terms of micro-, meso-, and macro-levels. Individual factors explain who is more and less generous, through genetic dispositions and social psychological orientations. In addition, people learn to give through their interpersonal social interactions, including the important role of families, particularly parents, in socializing children to give. Children also learn to give from non-parental socializing agents, including other adults and peers. Moreover, giving takes effort that can be inhibited by the busyness of everyday life. People need resources to sustain generous inclinations, and many of the Science of Generosity projects indicate the importance of social and cultural resources in sustaining generosity. Political and religious institutions also shape generosity in meaningful ways.

Individual Causes

While both genetic and social psychological orientations may be socially influenced [by lived experience], the relative stability of these causal factors implies that individuals will be more or less inclined to act generously as a result of their personal dispositions and characteristics.

Further considering individual-level factors, several social psychological orientations can guide how individuals interact interpersonally and participate, or not, in groups and organizations. With regard to social psychological orientations that impact generosity, researchers in the Science of Generosity project (Herzog and Price 2016) considered more than 100 different indicators that group within the following six categories: personality and wellbeing (such as depression, behavioral anxiety, sensation seeking, and extrovert-introvert), values and morals (such as materialism, consumerism, and moral relativism), life dispositions (such as having a gratitude outlook, prosperity perspective, and sucker aversion), relational styles (such as relational attachment, empathy, hospitality, and considering people to be all one human family), social milieu (such as experience of caring ethos, selflessness, belief in reciprocity, and trust in generosity systems), and charitable giving (such as responsibility to be generous, willingness to give more, awareness of giving options, and knowing about generosity outcomes).

Conducting a factor analysis of these many indicators, seven principal factors emerged: social solidarity, life purpose, collective consciousness, social trust, prosperity outlook, acquisition seeking, and social responsibility. Of these, high prosperity outlook (“there is plenty to go around”) and low acquisition seeking (“life is for the taking”) orientations are the strongest predictors of giving money. Social solidarity (“we’re all in it together”) and collective conscious (“we are all here to help each other”) orientations are also strong predictors of giving money. In terms of having an orientation to be a generous person, social solidarity is the strongest predictor, then come collective conscious, prosperity outlook, and social responsibility (“we are all our brother’s or sister’s keepers”). Based on the previous set of studies, it is likely that these orientations are formed through a combination of genetic and environmental factors. Once formed, these orientations appear to be guiding influences to act in generous ways, or not. People describe these orientations as helping to explain their individual inclinations toward generosity.

These individual-level orientations highlight the ways that people have personal agency in exercising the degree to which they want to engage in generous actions. Embedded within this agency are personal values that prospectively guide social actions (e.g. Hitlin and Piliavin 2004). Importantly, self-transcendence is a value that can lead people to focus beyond the self in pursuing the wellbeing of others.

… people with greater self-transcendence were more likely to regulate their negative emotions and capable of expressing positive affect (self-efficacy), as well as more able to sense the feelings of another and be aware of their need for emotional support (social efficacy), both of which in turn contributed to expressing greater empathy. Combined, self-transcendence and social-self efficacy contributed to an average of more than half (55 percent) of the variance in exhibiting generous behaviors. Thus, social psychological orientations are another important individual cause of generosity, which couple with genetic factors in explaining individual-level reasons why people are inclined to act generously, or are not so inclined.

Giving takes effort that can be inhibited by the busyness of everyday life. To be able to give, people require access to at least some economic, social, or psychological resources, and they must see those resources as available to give, worthy of giving, and plentiful enough to be given without great risk.

Family Causes

Shifting up the pyramid from individual-level causes, families are also importantly causal in shaping generosity. Often, family causes are thought to be downward-directing, in a focus on the ways that parents shape the generosity behaviors of children. … Additionally, Brown and colleagues investigated the ways that parenting itself can cause generosity, finding that the same caregiving system that activates in parent neural circuitry, in reacting to a crying baby, is also activated in other nonfamily-based generous and compassionate responses (Brown et al. n.d.; Swain et al. 2012; Swain and Ho 2017).

Also focusing on family causes, Gillath and colleagues studied the effect of parental attachment on child generosity (Mikulincer et al. 2005; Gillath et al. 2012). Attachment security refers to the sense that one is worthy of being loved and that people will be there when needed. While attachment security is often formed in early childhood, it can have long-lasting effects later in life, as young people emerge into adulthood.

On the basis of an attachment perspective, we believe that a sense of attachment security allows a redistribution of attention and resources, away from self-protection and toward other behavioral systems, including the caregiving system, which operates through such mechanisms as empathy and compassion (Mikulincer et al. 2005, p. 836).

… even if one did not have a strong attachment during childhood, that feeling securely attached as an emerging adult can still promote greater generosity. In this sense, generosity is malleable throughout the life course.

… children and teens respond to the role-modeling and teaching efforts of their parents. … “parents strongly influence the kinds of prosocial behavior exhibited by a wider fraction of the population”. … these studies indicate the significance of social learning, and the strong causal influence of family contexts in fostering generosity over time. Yet, many parents retreated their socialization efforts as teens aged, with 16 percent stopping talking to children about giving. These researchers stated that “our results imply that curtailing conversations causes a large reduction in the probability that a child gives” (Ottoni-Wilhelm et al. 2017, p. 222). Thus, families are important in causing generosity.

Interpersonal Causes

… children can learn to give from nonfamilial sources, as well as from families. Importantly, causal mechanisms continue to operate in fostering generosity throughout childhood and into adolescence, meaning that generosity is a malleable quality that can be continuously caused by a number of interpersonal interactions.

… interpersonal interactions, in the form of two-way communication, are important because it creates empathy, which in turn, fosters generosity. Likewise, serving in each other’s roles—perspective taking— also catalyzes empathy, which also in turn fosters generosity.

… “asking [for generosity], it seems, is both aversive and effective”. … Direct asks help raise short-term generosity, but if solicitations cause discomfort, then generosity may suffer in the longer term.

… people who had at least one giver within their close-to network have 1.68 greater odds of giving than those who do not have a giver within their close social network (Herzog and Yang 2018). Additionally, people with someone in their close network who asks them to give have 1.71 greater odds of giving than those without a solicitation to give within their close network.

Group, Community, and Organizational Causes

… group dynamics can helpfully produce generosity, but groups can also influence participants in ways that are not always positive, in the sense that coercion and conformity are inevitably also aspects of group dynamics. Free riders can also benefit from the collective effort exerted by other group members … group generosity can have a darker underbelly: members can selfishly gain from group generosity without contributing. To rectify this problem, this study finds that group members are willing to collectively impose punishments to minimize selfish free riding.

… while ethnic and religious diversity is generally desirable for communities, increased diversity can have unintended consequences for collective levels of generosity.

Institutional Causes

Social institutions can be understood as a type of social structure, which Smith (2010, pp. 346–347) defined as: frameworks for social interactions and durable patterns of human relations that are generated and reproduced in social interactions, accumulated and transformed historically, expressed through lived bodily practices, defined by culturally meaningful categories, motivated by normative guides, controlled and reinforced by sanctions, and which ultimately promote cooperation and conformity, discourage resistance and opposition, and result in hierarchies of social statuses, which are expressed as social inequalities. These social structures culminate in societies and cultures as a whole, involving interactions among multiple social institutions, such as religious, economic, educational, familial, and political institutions.

The culmination of findings from a mixed methodology of experiments, interviews, and case studies reveals that the community and togetherness aspects of religiosity are crucial for understanding religious motivations for generosity. This is distinct from a micro-level focus on beliefs, or a meso-level focus on organizational factors. Rather, institutionally, religiosity is also a collective social institution which provides an organizing framework for social interactions, including good deeds designed to benefit others beyond the self. Seen from this perspective, religion is similar to a political institution, in that it organizes personal beliefs in the provision of broader public goods.

… government grants do not appear to reduce individual-level generosity, but rather they damper meso-level generosity through organizational fundraising.

In summary, both political and religious institutional causes contribute to generosity. While institution-to-institution causes appear to zero out, in the case of government grants, institution-to-individual causes appear to contribute net gain, or have the potential to, at least in terms of the ways that religious institutional resources can be primed to foster greater individual-level generosity. More generally, these studies highlight the need to focus on multiple layers of the social force pyramid (Fig. 2.5). No one study alone can necessarily study multiple layers; yet, multiple studies can be accumulated around similar topics to reveal patterns across micro, meso, and macro units. Such an endeavor reveals complexities, but not insurmountable confusion. Realistic practical and policy implications can be derived from each layer of data, and the results of meso-level and macro-level studies reveal fungible mechanisms for creating change in net generosity levels, even with the predispositions of baseline individual-level genetic factors.

Societal and Cultural Causes

At the broadest level of the social force pyramid, societal and cultural causes involve shared values, norms, and beliefs. Within geopolitical boundaries, subcultural dynamics affect generosity through lifestyle choices and patterned preference choices (Bourdieu 1986).

… there is a link between social capital and generosity. Employing a National Statistics Social-economic Classification of occupational status reveals the professional and managerial class to be more engaged in generous activities, in terms of volunteering, informal helping, and charitable giving. Specifically, about three-quarters of the professional and managerial class engaged in these generous activities, on average, compared to about two-thirds of those employed as manual labor supervisors, and about half of manual labor workers. In summary, “people in higher class positions actually give significantly more in relative terms than those in lower classes” (Li 2015a, p. 48).

Social capital can be understood in many ways, including two primary forms: as resources embedded within social networks, and as a generalized sense of social trust in others. Focusing on the first domain, Li, Savage, and Warde (2015b) … find a relationship between social capital and cultural practices. People tend to share similar lifestyle choices with those whom they are similar to, in terms of social and economic statuses. For example, people in the professional and managerial class shared a high level of educational resources, which are highly transferred from parents to children, and education is a key predictor of cultural practices, including generosity. Cultural capital is also causal of generosity within informal social networks, which are translated into formal civic engagement activities (Li et al. 2015a). Considering the second domain—social trust—Li et al. (2018) find that “confidence in the moral orientation or trustworthiness of fellow citizens” (p. 1) has generally been stable over time, with about half of the British population expressing social trust, in a representative study of 1595 households. People with advanced educational levels account for a greater share of those who are socially trusting, with lower shares of social trust among people with less education. Moreover, people with higher degrees of social trust are more likely to be engaged in generous activities, across a variety of social and civic engagement forms.

… using data from longitudinal surveys and behavioral experiments, researchers investigated the “social contagion” of generosity: whether generosity can spread from one person to another and whether structural aspects of people’s social relationships affect how generous they are. Focusing on cooperation, these researchers found that cooperation “cascades” through networks, meaning that cooperation by one person was spread through their network, up to three degrees of separation from the original actor (in other words, a friend, of a friend, of a friend was also cooperative). Plus, cooperation is greater in networks that are regularly updated. Static network connections, which are not regularly pruned (such as through “friending” and “defriending”), were less likely to spread cooperation than updated networks.

Paxton et al. (2014) found religious capital contributed to greater volunteering, across multiple geopolitical and cultural boundaries. For example, Catholics in multiple countries were more likely to volunteer when they prayed in conjunction with attending religious services; for Protestants, both praying and service attendance had independent effects on volunteering. Moreover, a one unit increase in religious salience— the importance of one’s religion in daily life—increased volunteering propensity by about the same amount as did eight years of additional education. If considering boosts to volunteering as relatively exchangeable, one implication of this finding is that participating in religious activities is a more malleable social resource than are educational gains.

… “generalized social trust is experience-based and responsive to social interactions” (Paxton and Glanville 2015, p. 201). Even within a relatively short period of time, social trust grows or shrinks.

Consequences

Smith and Davidson (2014) tracked individual consequences to donors in a book entitled The Paradox of Generosity. The paradox was that results to givers are counter-rational: losing promotes gaining. Giving away resources returns personal wellbeing. The researchers summarized: “the more generous Americans are, the more happiness, health, and purpose in life they enjoy” (p. 2). … [distinguishing correlation from causation] psychological wellbeing was the causal factor resulting in both a consequence of greater happiness and more generosity. Complexly, those with greater psychological wellbeing may self-select into more generous behaviors, and also derive greater happiness from engaging in generous behaviors.

… as population size rises, generosity does not scale uniformly across all types of generous activities.

In summary, the consequences of generosity ripple outward … Beginning with the individual and micro-level: self-benefit entails consequences for the donor. Whether it is giving time, money, blood, or relational attention, generosity appears to benefit the giver, promoting better overall health and wellbeing. Rippling outward, generosity also promotes multiple consequences for interpersonal others. In marriages, being generous toward one’s spouse causes better outcomes for the couple and, for certain types of couples, promotes greater community generosity. Rippling outward to a third level, generosity in groups, organizations, and networks results in greater collective generosity and wellbeing. In a pay-it-forward mechanism, people who are the recipients of generosity in group settings cascade generosity onward and spread greater generosity throughout networks to new recipients, who in turn spread generosity onward. Rippling to the broadest level, generosity also appears to be beneficial for communities, cities, and societies generally (Gaudiani 2010). Although, of all the consequences of generosity, the broadest and most macro-level effects are, as of now, the least studied and thus least understood.

… generosity appears to have mostly positive consequences, across multiple social levels. Although, there are also some drawbacks to generosity, in terms of ways that collective giving can result in some group participants benefiting without carrying their full weight. Some studies indicate that punishments and other seemingly negative social mechanisms also result from generosity, but ultimately small-group enforcement of mild punishments appears to in turn promote greater generosity.

With regard to the consequences of generosity reviewed in this chapter, social scientists do not yet know enough about this domain to contribute robust understandings.