Global Issue Interconnections

20 Mar 2023Summary

There is no shortage of pressing problems in the world, enumerated by the United Nations (and respective Sustainable Development Goals), World Economic Forum, 80,000 hours, etc. These issues are highly interconnected, and making meaningful progress on one often requires domain knowledge on another. This is my attempt to map out those interdependencies and identify outsized areas of impact (w.r.t. problem prioritization, but also to identify fundamental topics/domains that one should learn about that are important to many systemic issues).

Takeaways include:

- Geopolitics, social unrest, the economy, and strong institutions are foundational to most issues. It’s difficult to make progress on an issue if one of these areas is in a poor state, so understanding general trends in them is important.

- Strategically prioritizing problems is important for effectiveness and efficiency, and priority is situational e.g. per country.

- Prioritizing basic and secondary needs (strong institutions, extreme poverty, access to essential services, gender equality, and governance) are perceived as more important than tackling higher-level systemic issues (e.g. climate change, urbanization).

- The Sustainable Development Goals typically synergize with one another (where success in one promotes success in the other), rather than posing trade-offs (where success in one comes at the cost of success in the other).

- None of the Sustainable Development Goals are fundamentally incompatible with another, but some have trade-offs that warrant careful consideration to support economic and social development within environmental limits.

My attempt at synthesis

Below is my basic attempt to draw connections between UN Global Issues. It was developed from reading summaries of each issue (supplemented by A Guide to SDG Interactions: from Science to Implementation), and noting challenges that block its progress, adjacent issues that will also benefit from its progress, or related topics that are necessary to understand it. It’s a superficial overview that lacks weighted importance between connections, and some issues are more thorough in drawing sub-issues and connections than others, but it provides a decent enough overview to understand systemic interactions.

An edge (arrow) from A → B indicates either A’s causality to B, or A’s importance in B’s solution. Nodes are sized based on how many outgoing edges they have, i.e. how causal or important they are to other issues. The original UN Global Issues are marked with a “UN” icon.

My conclusions are:

- Lack of access to basic services and gender inequality are at the root of many systemic issues (e.g. poverty, inequality, economic development)

- Similarly, economic development and the application of big data are “horizontal” beneath most issues and can advance progress on many issues simultaneously

Appendix

United Nations

The United Nations’ list of global issues reflect the issues the organization is trying to tackle through its Sustainable Development Goals, which aim to promote human development while balancing the economic, social, and environmental dimensions of sustainability. The SDGs represent a highly interlinked and indivisible agenda, with trade-offs and constraints in the implementation of goals to avoid detracting from others. Implementation is left up to each country, though the SDGs intentionally do not provide a plan of action or address the complexities and trade-offs that emerge.

SDGs In Order

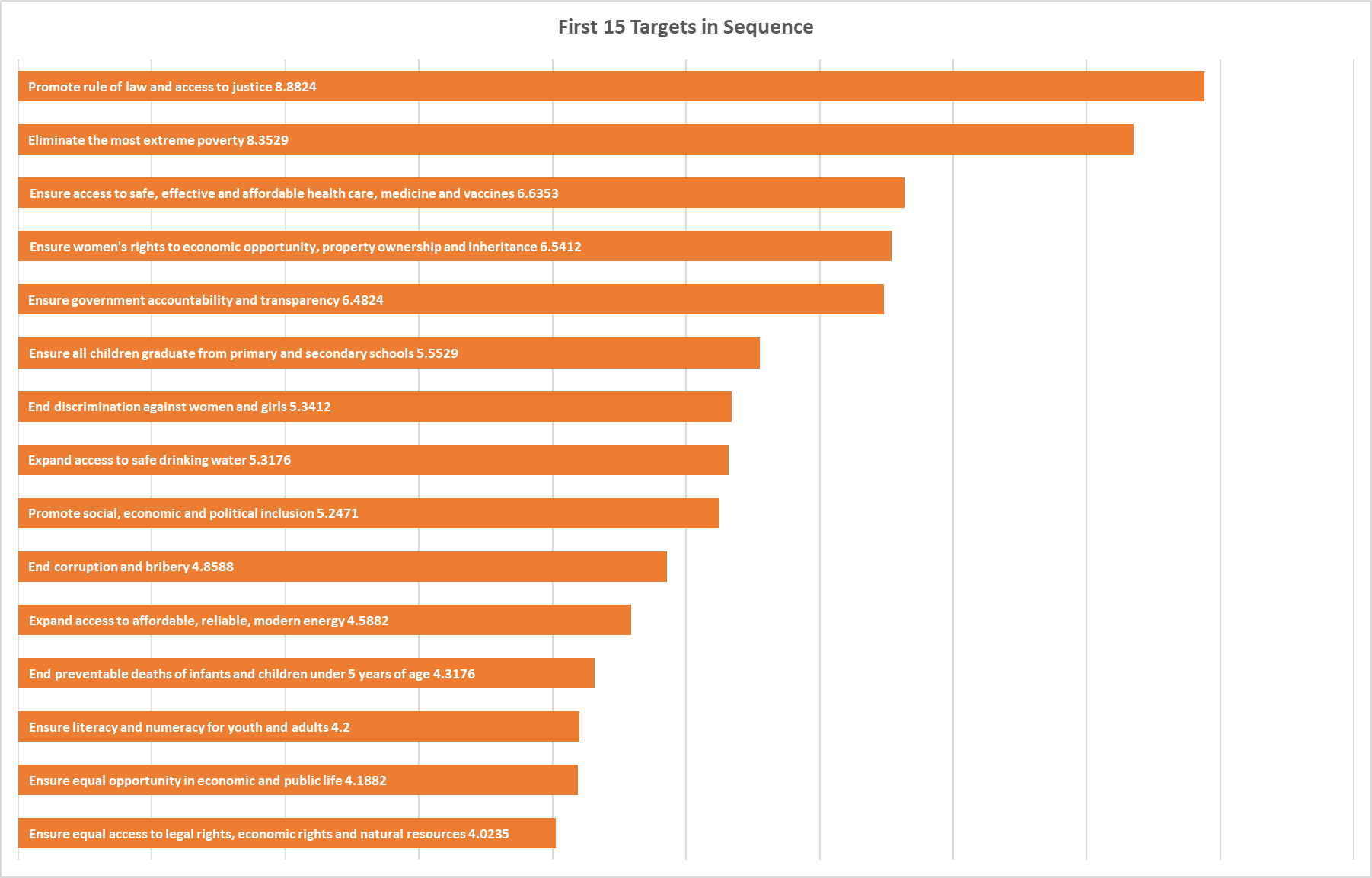

The SDGs have been criticized for their broad scope and lack of prioritization strategy (“[looking] more like an encyclopedia of development than a useful tool for action”). In response, New America and OECD created an ordering of the Sustainable Development Goals designed to optimize for stability in society and the state. They contend that a logical, ordered approach to tackling SDGs makes a significant difference in effectiveness over organizations and individuals pursuing their own specific issues due to self-interest. The ordering was created by surveying “economists, political scientists and social scientists working in public institutions, international organizations, foundations, universities, think tanks and civil society groups around the world”, and asking them to identify and sequence the first 20 SDG targets that should be tackled as part of an effort to fulfill all SDGs.

Targets to promote rule of law and access to justice, and eliminate the most extreme poverty, were perceived as significantly more important than the others:

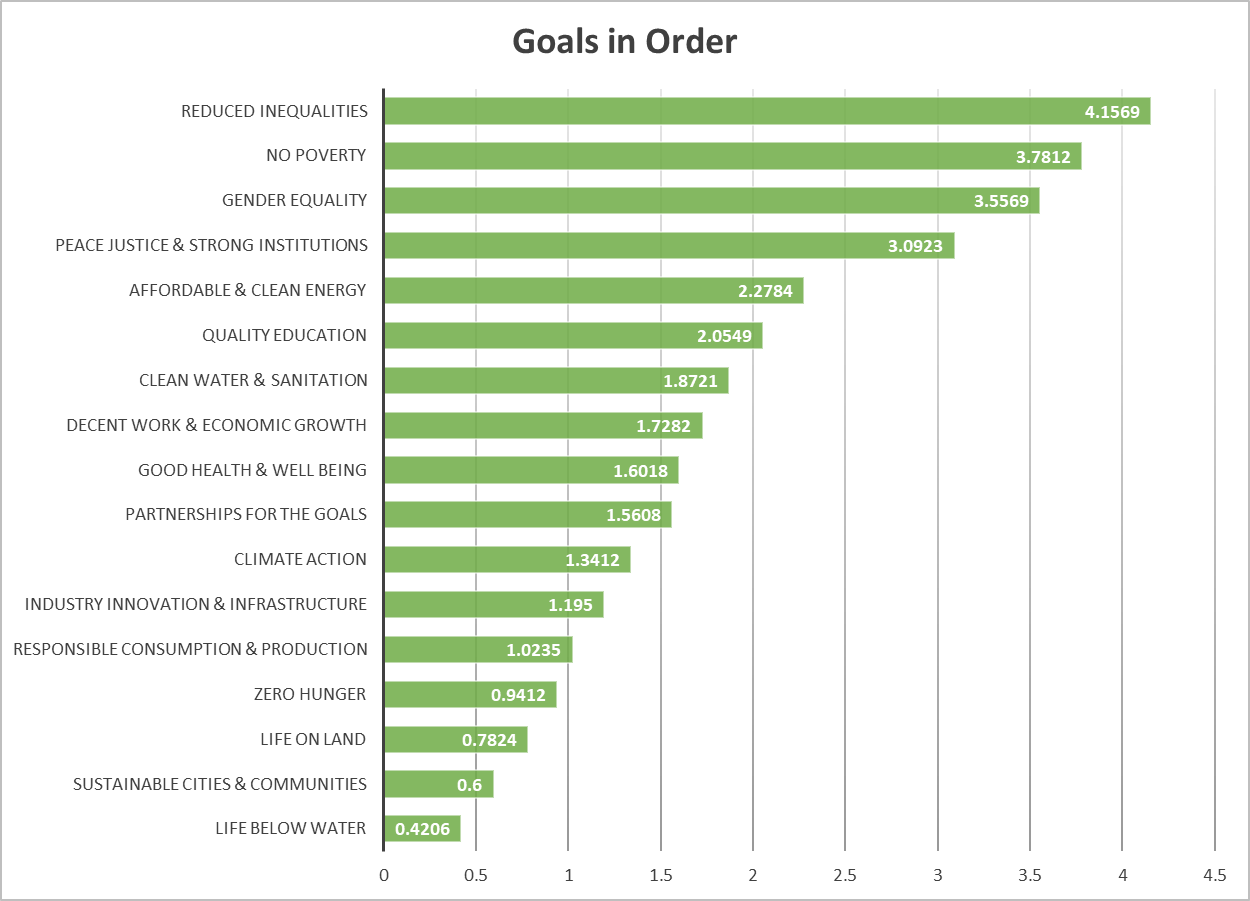

The targets chosen in the survey were mapped to their corresponding SDGs to rank the SDGs as well. Deviating from the target ordering, goals to reduce inequalities, eliminate poverty, achieve gender equality, and promote peace, justice, and strong institutions were perceived as significantly more important than the other SDGs:

The experts’ philosophies of prioritization were also categorized into approaches that optimize for empowering individuals vs. strengthening institutions, and having a deliberate, calculated approach vs. moving quickly to address the most pressing challenges. The majority of approaches were individualistic, with a relatively even split between deliberation vs. urgency.

SDG interactions (qualitative)

From A Guide to SDG Interactions: from Science to Implementation:

Although governments have stressed the integrated, indivisible and interlinked nature of the SDGs …, important interactions and interdependencies are generally not explicit in the description of the goals or their associated targets. … This report … [explores] the important interlinkages within and between these goals and associated targets to support a more strategic and integrated implementation. Specifically, the report presents a framework for characterising the range of positive and negative interactions between the various SDGs, … and tests this approach by applying it to an initial set of four SDGs: SDG2, SDG3, SDG7 and SDG14. This selection presents a mixture of key SDGs aimed at human well-being, ecosystem services and natural resources, but does not imply any prioritisation.

There aren’t many details on the report’s methodology, other than “the approach taken relied on an interpretive analytical process whereby research teams combine their knowledge and expert judgment with seeking of new evidence in the scientific literature and extensive deliberations about the character of different specific interactions”. I presume the teams mapped their understanding of target interactions to the numerical framework mentioned in the report, which categorizes the positivity or negativity of each interaction.

Some of my takeaways are:

This analysis found no fundamental incompatibilities between goals (i.e. where one target as defined in the 2030 Agenda would make it impossible to achieve another). However, it did identify a set of potential constraints and conditionalities that require coordinated policy interventions to shelter the most vulnerable groups, promote equitable access to services and development opportunities, and manage competing demands over natural resources to support economic and social development within environmental limits.

It should also be clear that a good development action is one where all negative interactions are avoided or at least minimised, while at the same time maximising significant positive interactions; but this by no means suggests that policymakers should avoid attempting progress in those targets and goals that are associated with significant negative interactions – it merely suggests that in these cases policymakers should tread more carefully when designing policies and strategies.

SDG16 (good governance) and SDG17 (means of implementation) are key to turning the potential for synergies into reality, although they are not always specifically highlighted as such throughout the report. For many if not all goals, having in place effective governance systems, institutions, partnerships, and intellectual and financial resources is key to an effective, efficient and coherent approach to implementation.

Given budgetary, political and resource constraints, as well as specific needs and policy agendas, countries are likely to prioritise certain goals, targets and indicators over others. As a result of the positive and negative interactions between goals and targets, this prioritisation could lead to negative developments for ‘nonprioritised’ goals and targets. … due to globalisation and increasing trade of goods and services, many policies and other interventions have implications that are transboundary in nature, such that pursuing objectives in one region can impact on other countries or regions’ pursuit of their objectives.

The following types of dependencies within a pair of goals/targets can be useful to contextualize their relationship/interactions:

- Directionality: whether the interaction is unidirectional, bidirectional, circular, or multiple

- Place-specific context: scale of the interaction, e.g. highly location-specific vs. generic across borders

- Governance: does poor governance create or amplify a negative relationship between the goals/targets?

- Technology: do technologies exist that can significantly mitigate the trade-off between the goals/targets?

- Time-frame: will the (positive or negative) interaction develop in real-time vs. over a long period of time?

Policies developed to address the SDGs should be coherent, i.e. systematically reduce conflicts and promote synergies between and within different policy areas to achieve policy objectives. Policy coherence is comprised of the following dimensions:

- Sectoral: coherent from one policy sector to another

- Transnational: observing to what extent the pursuit of objectives in one country will affect the ability of another to pursue its sovereign objectives

- Governance: coherent from one set of interventions to another

- e.g. legal frameworks, investment frameworks, and policy instruments all pull in the same direction

- It is often the case that while new policies and goals can be easily introduced, institutional capacities for implementation are not aligned with the new policy designs, because the former are commonly more difficult to develop

- Multilevel: coherent across multiple levels of government (international/national/local)

- Implementation: coherent along the implementation continuum: from policy objective, through instruments and measures agreed, to implementation on the ground

- The latter often deviates substantially from the original policy intentions, as actors make their interpretations and institutional barriers and drivers influence their response to the policy

Takeaways on specific SDG interactions are included in the synthesized interactions graph above.

SDG interactions (quantitative)

A Systematic Study of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Interactions builds upon the previous (ISCU) qualitative analysis of SDG interactions by performing a statistical analysis of SDG indicators from country and country-disaggregated data. They capture interaction synergies and trade-offs by identifying significant positive and negative correlations in the indicator data.

They found the following SDG pairs have the most synergies and trade-offs:

The observed positive correlations between the SDGs have mainly two explanations. First, indicators of the SDGs depicting higher synergies consist of development indicators that are part of the MDGs and components of several development indices …. Second, the observed higher synergies among some SDGs are an effect of having the same indicator for multiple SDGs.

Most trade-offs … can be linked to the traditional nonsustainability development paradigm focusing on economic growth to generate human welfare at the expenses of environmental sustainability …. On average developed countries provide better human welfare but are locked-in to larger environmental and material footprints which need to be substantially reduced to achieve SDG 12 (Responsible consumption and production).

We are aware that correlation does not imply causality. This means observed synergies between two SDG indicators could be independently related to another process driving both indicators and therefore resulting in correlations. However, because the correlation analysis is done for indicator pairs in each country individually, the existence of a large number of synergies (or trade-offs) suggests that the relation is widespread across many countries and most likely not appearing by chance.

Takeaways include:

- The conclusions from this quantitative study are largely in agreement with the qualitative ISCU study: there are typically more synergies than trade-offs within and among the SDGs in most countries, and fostering cross-sectoral and cross-goal synergetic relations will play a crucial role in operationalization of the SDG agenda.

- SDG 1 (No poverty) is associated with synergies across most SDGs and ranks five times in the global top-10 synergy pair list.

- Reducing poverty is statistically linked with progress in SDGs 3 (Good health and wellbeing), 4 (Quality education), 5 (Gender equality), 6 (Clean water and sanitation), or 10 (Reduced inequalities) for 75%–80% of the data pairs.

- Improvement of global health and well-being has highly been compatible with progress in SDGs 1 (Poverty reduction), 4 (Quality education), 5 (Gender equality), 6 (Provision of clean water and sanitation), and SDG 10 (Inequalities reduction) based on more than 70% of the data pairs.

- SDG 3 (Good health and well-being) was found to have a higher share of synergies with other SDGs in most of the countries and the world population …. Hence, a paradigm shift prioritizing good health and well-being, for example, by inter-sectoral and prevention based approaches, will have a greater impact than the conventional approaches … and will also leverage attainment of other SDGs.

- The global top 10 pairs with trade-offs either consist of SDG 12 (Responsible consumption and production) or 15 (Life on land).

- SDGs 8 (Decent work and economic growth), 9 (Industry, innovation, and infrastructure), 12 (Responsible consumption and production), and 15 (Life on land) are associated with a high fraction of trade-offs across SDGs.

World Economic Forum

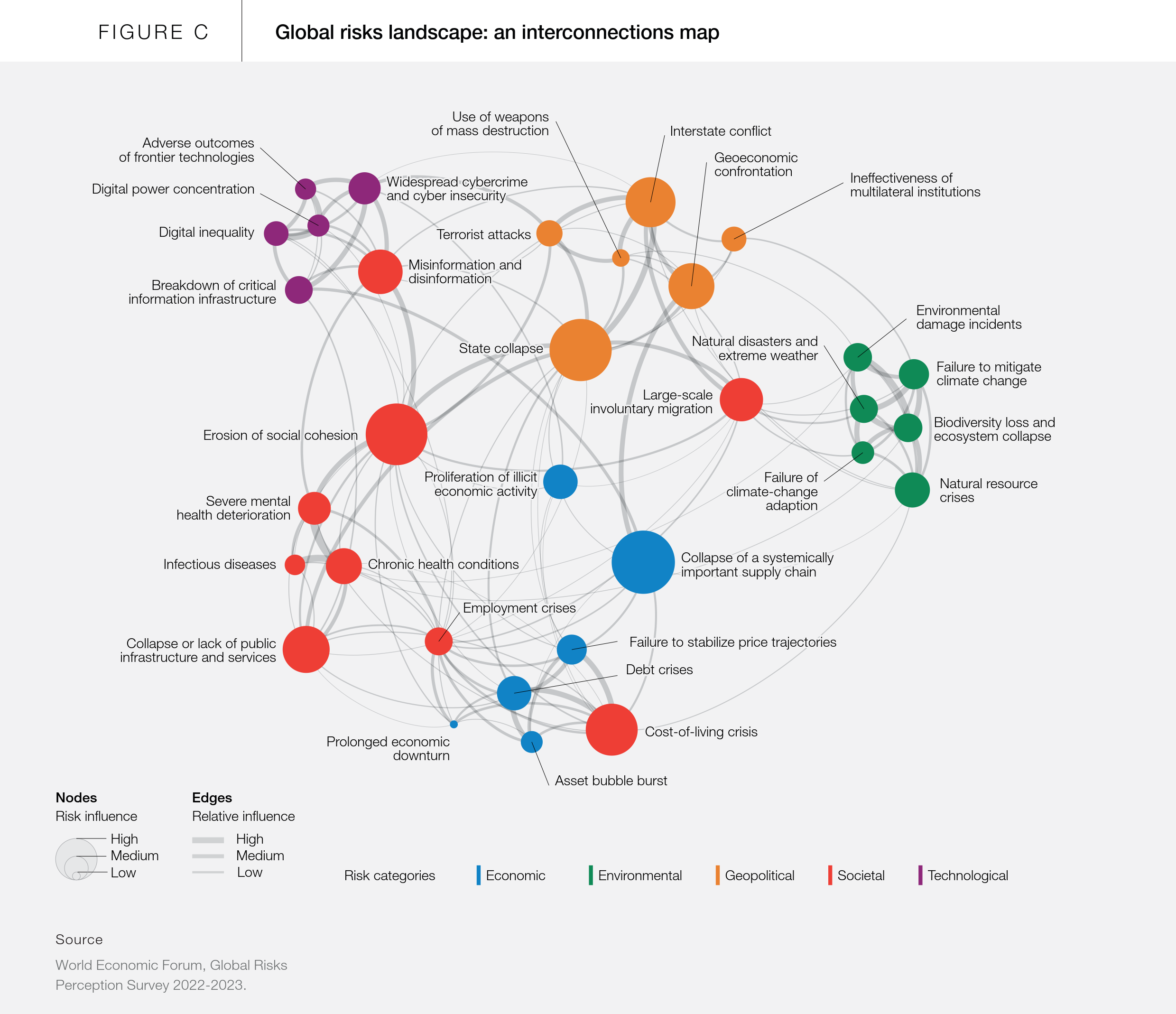

The World Economic Forum generates an annual Global Risks Report by surveying their “extensive network of academic, business, government, civil society and thought leaders” about their largest perceived global risks. These reports rank the importance of issues over short- (2-year), medium- (5-year), and long-term (10-year) horizons, and often feature a map of interconnections between issues with weighted causality, which is relevant to the objectives of this post.

However, it seems the risks are primarily relative to governments and businesses, have an elite-centric perspective, and do not consider fundamental issues affecting individuals (e.g. poverty and gender equality) to be “risks”. Additionally, the reports seem inconsistent in their long-term risk perceptions, and follow trends and FUD du jour. Nevertheless, they provide an additional perspective on interconnection and causality, to be taken with a grain of salt.

Causality

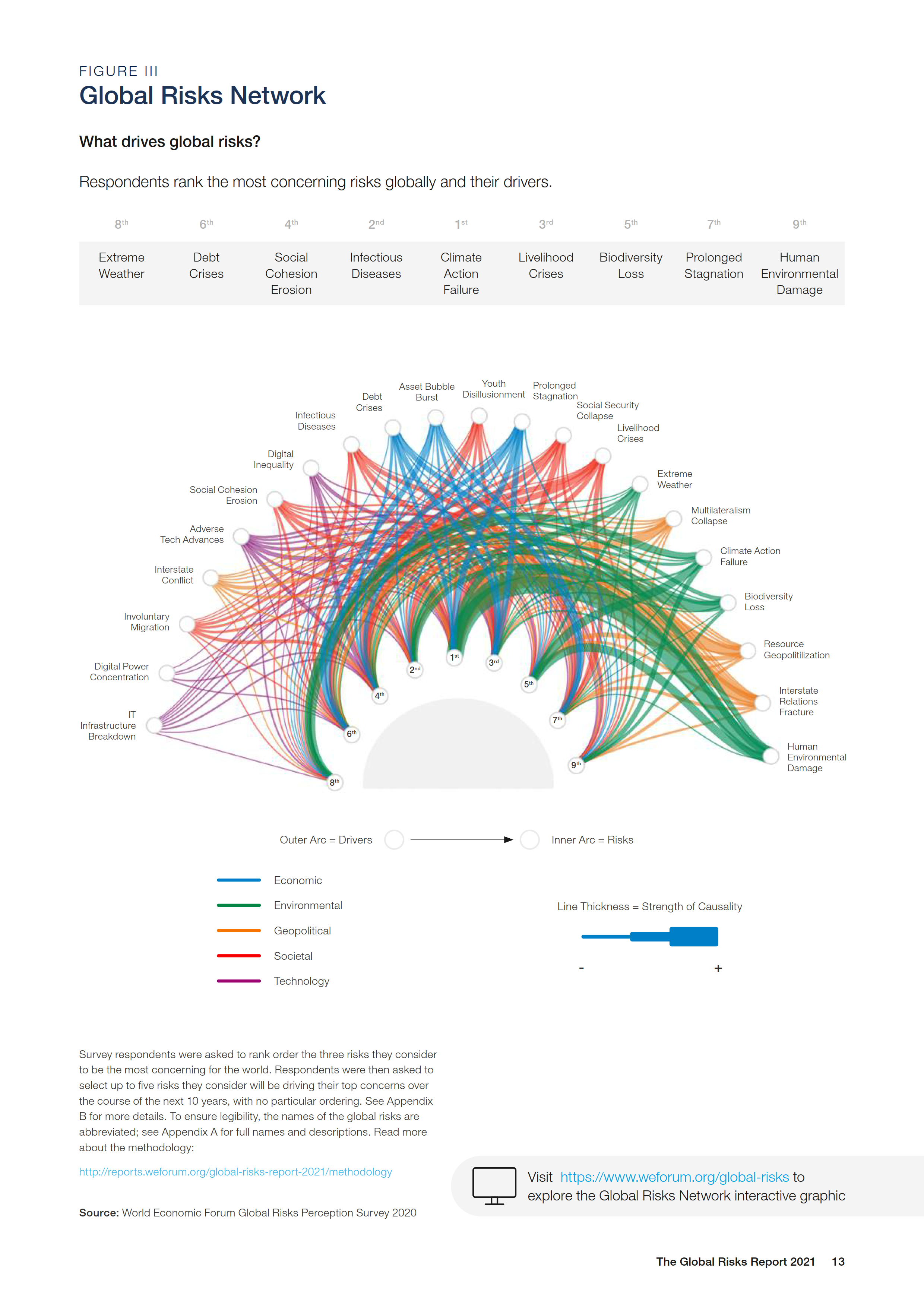

Since 2021, the WEF reports have included a section that analyzes causality and downstream effects between issues. These are included below, with my respective conclusions under each year.

In 2023, the following risks were identified as especially consequential if they were to be triggered. This doesn’t necessarily indicate high individual impact/severity of these risks, but rather high influence for exacerbating other issues. An interactive version is available here under the “Causes & Consequences” tab.

- Cohesion is tightly coupled between the societal, geopolitical, and economic spheres; if one sphere collapses, it has significant consequences for the others

2022’s report shows the perceived downstream effects of the top 5 most severe 10-year risks; interactive version here, under “Global Risks Effects”.

- Climate action failure leads to further damage in the environmental and societal spheres (involuntary migration, livelihood crises, and social cohesion erosion)

2021’s report shows the perceived drivers (opposite of 2022) of the top 5 most severe 10-year risks; interactive version here.

- Climate action failure and human environmental damage reinforce one another

- Climate action is impeded by geopolitical issues (interstate relations, resources, multilateralism), economic issues (stagnation, debt), and societal issues (livelihood crises, social cohesion erosion), in that order

- Livelihood crises are caused by a relatively even distribution of societal factors (social security collapse and diseases (COVID)), economic factors (stagnation and debt), and technological factors (to a lesser extent than the others; digital inequality and adverse tech advances)

- Social cohesion erosion is primarily driven by other societal factors (livelihood crises, social security collapse, youth disillusionment, involuntary migration), and technological factors to a lesser extent (digital inequality, adverse tech advances)

Interconnections

Prior to 2021, the reports analyzed risk interconnections (without causality) by surveying “the most strongly connected” pairs of global risks. Interactive versions of this section of the report are available for 2020, 2019, and 2018. Node size and edge weight are based on number of appearances (of a given risk, or pair of risks, respectively) in survey results.

Risk pairs that were consistently perceived as strongly connected include:

- State collapse or crisis & involuntary migration

- Interstate conflict & involuntary migration

- Unemployment & social instability

- Climate action failure & extreme weather