18 Jul 2023

What is the goal of behaviors that seek to benefit others, such as acts of generosity or pursuing (scientific/economic/social) progress? Increasing well-being is a commonly-accepted answer; but what does that mean?

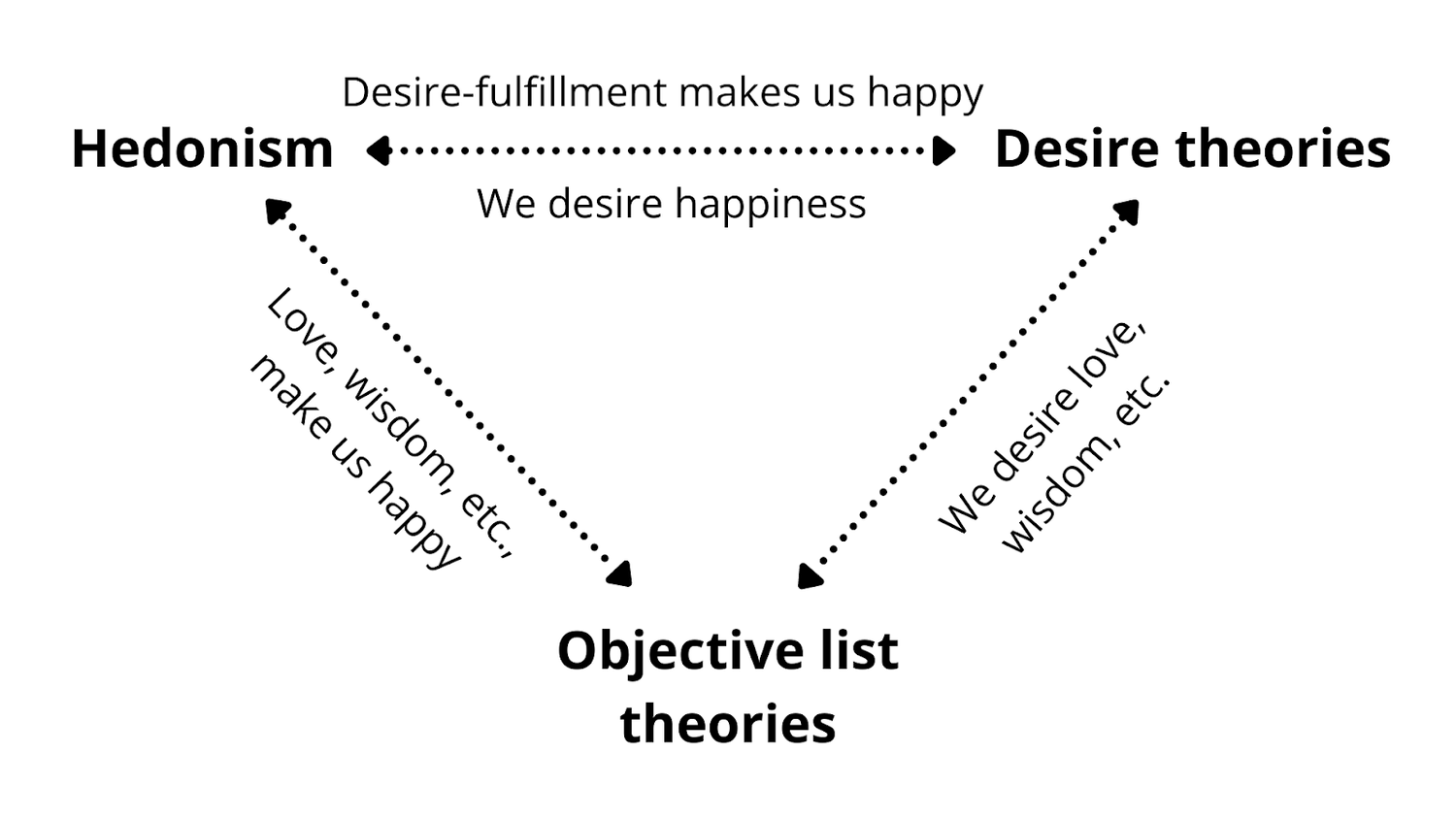

Philosophically, well-being usually refers to how well a person’s life is going for them. In defining well-being, we need to distinguish between what inherently contributes to well-being (such as happiness), and what is a means (or instrument) to well-being (such as money). There is consensus that a person’s well-being consists of the former: things that in themselves are good for them; but there’s disagreement on what those things actually are.

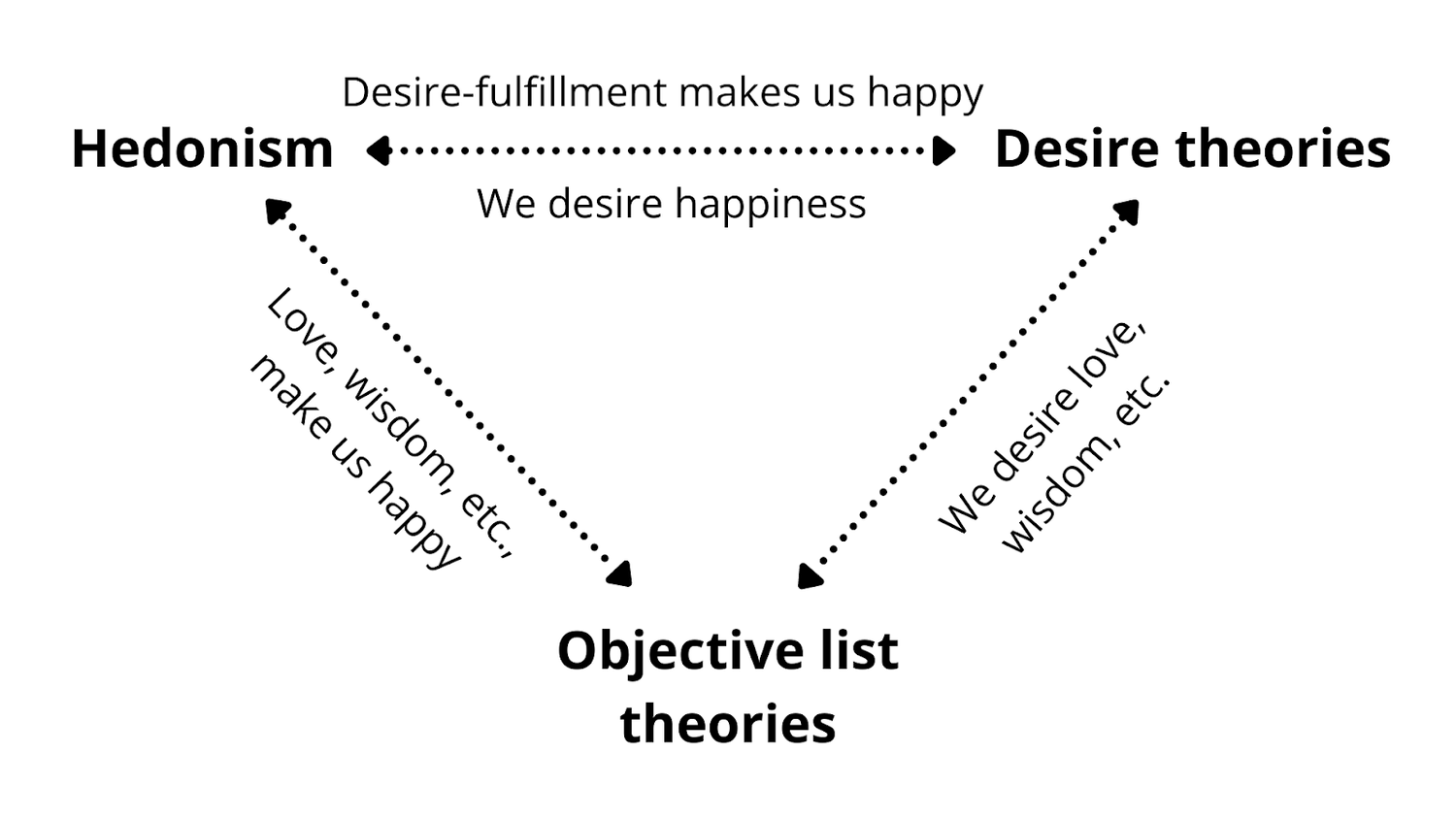

There are three main categories of theories for what constitutes well-being, crudely paraphrased below:

- Hedonism: an overall positive balance of pleasure (i.e. happiness) over pain

- Desire theories: having one’s preferences fulfilled

- Objective list theories: a list of things that objectively make someone’s life better, regardless of whether they are consciously pleasurable or desired

These articles provide a deeper look into these theories and their points of contention.

Some additional notes to clarify related terms:

- Happiness isn’t necessarily the same thing as well-being, but happiness can be part of well-being

- Happiness has short-term and long-term components; the latter can be understood as life satisfaction (i.e. being content with one’s life)

- Well-being theories based on life satisfaction are usually considered to be their own category, separate from the main three

- The concept of eudaimonia is an objective list theory

Tying this back to prosocial behavior: these theories of well-being are relevant in choosing how we want to benefit others. We can try to increase others’ happiness, empower them to fulfill their desires, or promote something within an objective list (such as success, friendship, knowledge, virtuous behavior, or health); each of these outcomes would be valued differently, depending on which well-being theory one subscribes to.

Though while these theories are useful for reflecting on the nuances of what’s good for us, their differences aren’t as important in practice, as most theories of well-being share common themes of what’s good for someone. For most proposed constituents of well-being (e.g. happiness, wisdom), each theory has a way to justify it, as illustrated below. This is because we tend to desire things that are (typically regarded as) objectively worthwhile, and we tend to be happier when we achieve what we desire. We may also tend to reshape our desires based on our experiences of what feels good.

04 Jun 2023

Summary

What causes people to behave in ways that are intended to benefit others (or society as a whole)? These behaviors include a wide variety of activities (from e.g. obeying rules and conforming to socially acceptable behavior, to donating, volunteering, helping, and treating others with kindness), and are important for individual and societal flourishing. One’s life experience can push them towards generous behavior, or antisocial behavior on the other hand, which begs the question of the causes behind generous behavior so it can be realized.

The causes of generosity are complex and multiple, and there is no single explanation for why people act generously. Most research focuses on correlation rather than causation, though The Science of Generosity provides an overview of known causal factors:

- “Blank slate” factors (without having been shaped by life experience):

- Biological (psychological reward - makes us feel good)

- Children appear to have an innate drive to help others, which is later shaped by their life experience

- Individual factors:

- Feelings of empathy, compassion, and other emotions

- Certain personality traits, such as humility and agreeableness

- Values, morals, and sense of identity

- Social and cultural factors:

- Expectation of reciprocation or that their generosity will help their reputation

- Cultural standards of fairness

- Strong social networks

- Other factors that are more nuanced and varied:

- Socioeconomic status

- People are more likely to help a specific person than an abstract or anonymous individual

- People are more likely to help individuals than groups

- Geographic factors (e.g. regional level of trust, city size, diversity)

- Governmental factors (e.g. crowding out individual donations, presence of strong institutions)

- Parenting practices (role-modeling and discussing generosity)

- Prosocial messages in media

- Timing or setting of request

What is generous behavior?

Several terms are used to describe behaviors that benefit others, including “prosocial”, “generous”, and “altruistic”, each with varying implications for the intent and ultimate outcomes of the behavior. Generally, “prosocial” or “generous” refer to behavior that benefits others, but can also benefit the self; whereas “altruistic” behaviors have a purely unselfish interest in helping others. There is debate on whether truly altruistic behavior exists, due to expectations of reciprocity or derived feelings of pleasure. This post focuses on the broader “generous” definition for simplicity.

The Science of Generosity: Causes, Manifestations, and Consequences describes the ways generosity can manifest:

In the Science of Generosity Initiative, as well as in other scholarship, scholars conceive of generosity as including a broad range of activities, such as financial donations to charitable causes, volunteering, taking political action, donating blood and organs, and informal helping. This definition includes the giving of money, possessions, bodily materials, time, or talent in the form of formal volunteering, assistance in the form of informal helping, attention and affection in the form of relational generosity, compassion and empathy, and many other activities that are intended to enhance the wellbeing of others, beyond the self. Many of these activities occur through organizations, such as nonprofit organizations with tax-exempt status. However, the activities need not occur through organizations and can occur instead through interpersonal, group, and other collective interactions. People can also be relationally generous to one another [being “generous with one’s attention and emotions in relationships with other people”].

The Science of Generosity: Causes, Manifestations, and Consequences

The Science of Generosity: Causes, Manifestations, and Consequences confirms the findings of (the similarly-named) The Science of Generosity whitepaper, and adds depth to its conclusions.

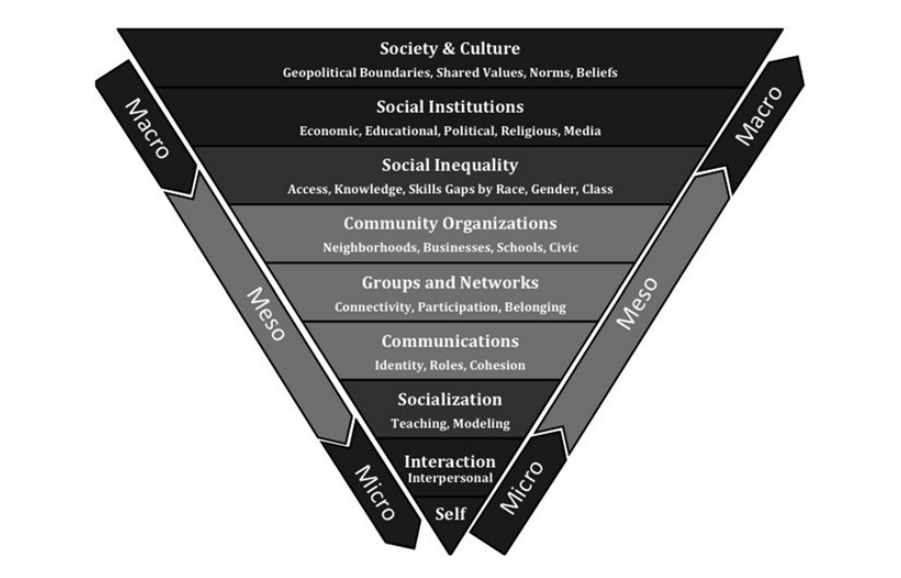

Summary

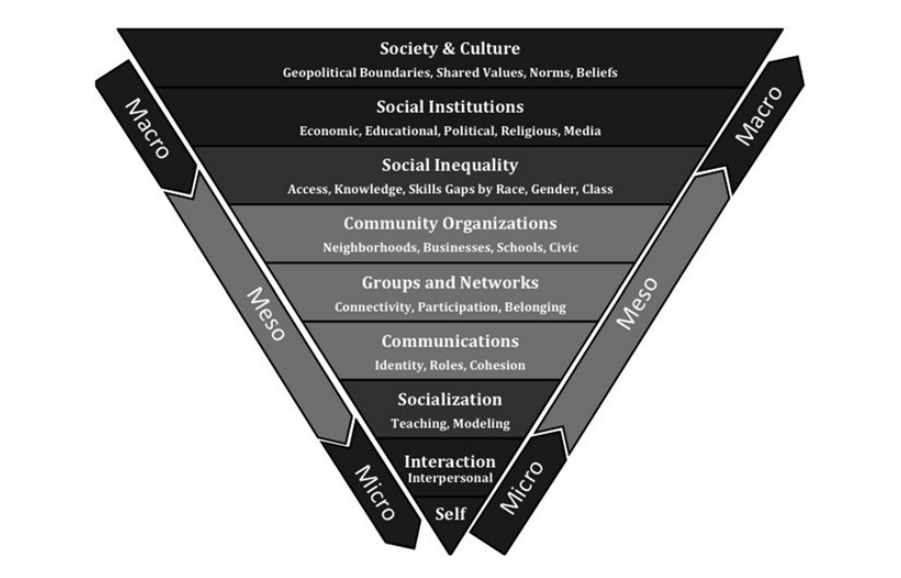

In summary, there are multiple causes of generosity, which can be categorized according to levels of social forces, in terms of micro-, meso-, and macro-levels. Individual factors explain who is more and less generous, through genetic dispositions and social psychological orientations. In addition, people learn to give through their interpersonal social interactions, including the important role of families, particularly parents, in socializing children to give. Children also learn to give from non-parental socializing agents, including other adults and peers. Moreover, giving takes effort that can be inhibited by the busyness of everyday life. People need resources to sustain generous inclinations, and many of the Science of Generosity projects indicate the importance of social and cultural resources in sustaining generosity. Political and religious institutions also shape generosity in meaningful ways.

Individual Causes

While both genetic and social psychological orientations may be socially influenced [by lived experience], the relative stability of these causal factors implies that individuals will be more or less inclined to act generously as a result of their personal dispositions and characteristics.

Further considering individual-level factors, several social psychological orientations can guide how individuals interact interpersonally and participate, or not, in groups and organizations. With regard to social psychological orientations that impact generosity, researchers in the Science of Generosity project (Herzog and Price 2016) considered more than 100 different indicators that group within the following six categories: personality and wellbeing (such as depression, behavioral anxiety, sensation seeking, and extrovert-introvert), values and morals (such as materialism, consumerism, and moral relativism), life dispositions (such as having a gratitude outlook, prosperity perspective, and sucker aversion), relational styles (such as relational attachment, empathy, hospitality, and considering people to be all one human family), social milieu (such as experience of caring ethos, selflessness, belief in reciprocity, and trust in generosity systems), and charitable giving (such as responsibility to be generous, willingness to give more, awareness of giving options, and knowing about generosity outcomes).

Conducting a factor analysis of these many indicators, seven principal factors emerged: social solidarity, life purpose, collective consciousness, social trust, prosperity outlook, acquisition seeking, and social responsibility. Of these, high prosperity outlook (“there is plenty to go around”) and low acquisition seeking (“life is for the taking”) orientations are the strongest predictors of giving money. Social solidarity (“we’re all in it together”) and collective conscious (“we are all here to help each other”) orientations are also strong predictors of giving money. In terms of having an orientation to be a generous person, social solidarity is the strongest predictor, then come collective conscious, prosperity outlook, and social responsibility (“we are all our brother’s or sister’s keepers”). Based on the previous set of studies, it is likely that these orientations are formed through a combination of genetic and environmental factors. Once formed, these orientations appear to be guiding influences to act in generous ways, or not. People describe these orientations as helping to explain their individual inclinations toward generosity.

These individual-level orientations highlight the ways that people have personal agency in exercising the degree to which they want to engage in generous actions. Embedded within this agency are personal values that prospectively guide social actions (e.g. Hitlin and Piliavin 2004). Importantly, self-transcendence is a value that can lead people to focus beyond the self in pursuing the wellbeing of others.

… people with greater self-transcendence were more likely to regulate their negative emotions and capable of expressing positive affect (self-efficacy), as well as more able to sense the feelings of another and be aware of their need for emotional support (social efficacy), both of which in turn contributed to expressing greater empathy. Combined, self-transcendence and social-self efficacy contributed to an average of more than half (55 percent) of the variance in exhibiting generous behaviors. Thus, social psychological orientations are another important individual cause of generosity, which couple with genetic factors in explaining individual-level reasons why people are inclined to act generously, or are not so inclined.

Giving takes effort that can be inhibited by the busyness of everyday life. To be able to give, people require access to at least some economic, social, or psychological resources, and they must see those resources as available to give, worthy of giving, and plentiful enough to be given without great risk.

Family Causes

Shifting up the pyramid from individual-level causes, families are also importantly causal in shaping generosity. Often, family causes are thought to be downward-directing, in a focus on the ways that parents shape the generosity behaviors of children. … Additionally, Brown and colleagues investigated the ways that parenting itself can cause generosity, finding that the same caregiving system that activates in parent neural circuitry, in reacting to a crying baby, is also activated in other nonfamily-based generous and compassionate responses (Brown et al. n.d.; Swain et al. 2012; Swain and Ho 2017).

Also focusing on family causes, Gillath and colleagues studied the effect of parental attachment on child generosity (Mikulincer et al. 2005; Gillath et al. 2012). Attachment security refers to the sense that one is worthy of being loved and that people will be there when needed. While attachment security is often formed in early childhood, it can have long-lasting effects later in life, as young people emerge into adulthood.

On the basis of an attachment perspective, we believe that a sense of attachment security allows a redistribution of attention and resources, away from self-protection and toward other behavioral systems, including the caregiving system, which operates through such mechanisms as empathy and compassion (Mikulincer et al. 2005, p. 836).

… even if one did not have a strong attachment during childhood, that feeling securely attached as an emerging adult can still promote greater generosity. In this sense, generosity is malleable throughout the life course.

… children and teens respond to the role-modeling and teaching efforts of their parents. … “parents strongly influence the kinds of prosocial behavior exhibited by a wider fraction of the population”. … these studies indicate the significance of social learning, and the strong causal influence of family contexts in fostering generosity over time. Yet, many parents retreated their socialization efforts as teens aged, with 16 percent stopping talking to children about giving. These researchers stated that “our results imply that curtailing conversations causes a large reduction in the probability that a child gives” (Ottoni-Wilhelm et al. 2017, p. 222). Thus, families are important in causing generosity.

Interpersonal Causes

… children can learn to give from nonfamilial sources, as well as from families. Importantly, causal mechanisms continue to operate in fostering generosity throughout childhood and into adolescence, meaning that generosity is a malleable quality that can be continuously caused by a number of interpersonal interactions.

… interpersonal interactions, in the form of two-way communication, are important because it creates empathy, which in turn, fosters generosity. Likewise, serving in each other’s roles—perspective taking— also catalyzes empathy, which also in turn fosters generosity.

… “asking [for generosity], it seems, is both aversive and effective”. … Direct asks help raise short-term generosity, but if solicitations cause discomfort, then generosity may suffer in the longer term.

… people who had at least one giver within their close-to network have 1.68 greater odds of giving than those who do not have a giver within their close social network (Herzog and Yang 2018). Additionally, people with someone in their close network who asks them to give have 1.71 greater odds of giving than those without a solicitation to give within their close network.

Group, Community, and Organizational Causes

… group dynamics can helpfully produce generosity, but groups can also influence participants in ways that are not always positive, in the sense that coercion and conformity are inevitably also aspects of group dynamics. Free riders can also benefit from the collective effort exerted by other group members … group generosity can have a darker underbelly: members can selfishly gain from group generosity without contributing. To rectify this problem, this study finds that group members are willing to collectively impose punishments to minimize selfish free riding.

… while ethnic and religious diversity is generally desirable for communities, increased diversity can have unintended consequences for collective levels of generosity.

Institutional Causes

Social institutions can be understood as a type of social structure, which Smith (2010, pp. 346–347) defined as: frameworks for social interactions and durable patterns of human relations that are generated and reproduced in social interactions, accumulated and transformed historically, expressed through lived bodily practices, defined by culturally meaningful categories, motivated by normative guides, controlled and reinforced by sanctions, and which ultimately promote cooperation and conformity, discourage resistance and opposition, and result in hierarchies of social statuses, which are expressed as social inequalities. These social structures culminate in societies and cultures as a whole, involving interactions among multiple social institutions, such as religious, economic, educational, familial, and political institutions.

The culmination of findings from a mixed methodology of experiments, interviews, and case studies reveals that the community and togetherness aspects of religiosity are crucial for understanding religious motivations for generosity. This is distinct from a micro-level focus on beliefs, or a meso-level focus on organizational factors. Rather, institutionally, religiosity is also a collective social institution which provides an organizing framework for social interactions, including good deeds designed to benefit others beyond the self. Seen from this perspective, religion is similar to a political institution, in that it organizes personal beliefs in the provision of broader public goods.

… government grants do not appear to reduce individual-level generosity, but rather they damper meso-level generosity through organizational fundraising.

In summary, both political and religious institutional causes contribute to generosity. While institution-to-institution causes appear to zero out, in the case of government grants, institution-to-individual causes appear to contribute net gain, or have the potential to, at least in terms of the ways that religious institutional resources can be primed to foster greater individual-level generosity. More generally, these studies highlight the need to focus on multiple layers of the social force pyramid (Fig. 2.5). No one study alone can necessarily study multiple layers; yet, multiple studies can be accumulated around similar topics to reveal patterns across micro, meso, and macro units. Such an endeavor reveals complexities, but not insurmountable confusion. Realistic practical and policy implications can be derived from each layer of data, and the results of meso-level and macro-level studies reveal fungible mechanisms for creating change in net generosity levels, even with the predispositions of baseline individual-level genetic factors.

Societal and Cultural Causes

At the broadest level of the social force pyramid, societal and cultural causes involve shared values, norms, and beliefs. Within geopolitical boundaries, subcultural dynamics affect generosity through lifestyle choices and patterned preference choices (Bourdieu 1986).

… there is a link between social capital and generosity. Employing a National Statistics Social-economic Classification of occupational status reveals the professional and managerial class to be more engaged in generous activities, in terms of volunteering, informal helping, and charitable giving. Specifically, about three-quarters of the professional and managerial class engaged in these generous activities, on average, compared to about two-thirds of those employed as manual labor supervisors, and about half of manual labor workers. In summary, “people in higher class positions actually give significantly more in relative terms than those in lower classes” (Li 2015a, p. 48).

Social capital can be understood in many ways, including two primary forms: as resources embedded within social networks, and as a generalized sense of social trust in others. Focusing on the first domain, Li, Savage, and Warde (2015b) … find a relationship between social capital and cultural practices. People tend to share similar lifestyle choices with those whom they are similar to, in terms of social and economic statuses. For example, people in the professional and managerial class shared a high level of educational resources, which are highly transferred from parents to children, and education is a key predictor of cultural practices, including generosity. Cultural capital is also causal of generosity within informal social networks, which are translated into formal civic engagement activities (Li et al. 2015a). Considering the second domain—social trust—Li et al. (2018) find that “confidence in the moral orientation or trustworthiness of fellow citizens” (p. 1) has generally been stable over time, with about half of the British population expressing social trust, in a representative study of 1595 households. People with advanced educational levels account for a greater share of those who are socially trusting, with lower shares of social trust among people with less education. Moreover, people with higher degrees of social trust are more likely to be engaged in generous activities, across a variety of social and civic engagement forms.

… using data from longitudinal surveys and behavioral experiments, researchers investigated the “social contagion” of generosity: whether generosity can spread from one person to another and whether structural aspects of people’s social relationships affect how generous they

are. Focusing on cooperation, these researchers found that cooperation “cascades” through networks, meaning that cooperation by one person was spread through their network, up to three degrees of separation from the original actor (in other words, a friend, of a friend, of a friend was also cooperative). Plus, cooperation is greater in networks that are regularly

updated. Static network connections, which are not regularly pruned (such as through “friending” and “defriending”), were less likely to spread cooperation than updated networks.

Paxton et al. (2014) found religious capital contributed to greater volunteering, across multiple geopolitical and cultural boundaries. For example, Catholics in multiple countries were more likely to volunteer when they prayed in conjunction with attending religious services; for Protestants, both praying and service attendance had independent effects on volunteering. Moreover, a one unit increase in religious salience— the importance of one’s religion in daily life—increased volunteering propensity by about the same amount as did eight years of additional education. If considering boosts to volunteering as relatively exchangeable, one implication of this finding is that participating in religious activities is a more malleable social resource than are educational gains.

… “generalized social trust is experience-based and responsive to social interactions” (Paxton and Glanville 2015, p. 201). Even within a relatively short period of time, social trust grows or shrinks.

Consequences

Smith and Davidson (2014) tracked individual consequences to donors in a book entitled The Paradox of Generosity. The paradox was that results to givers are counter-rational: losing promotes gaining. Giving away resources returns personal wellbeing. The researchers summarized: “the more generous Americans are, the more happiness, health,

and purpose in life they enjoy” (p. 2). … [distinguishing correlation from causation] psychological wellbeing was the causal factor resulting in both a consequence of greater happiness and more generosity. Complexly, those with greater psychological wellbeing may self-select into more generous behaviors, and also derive greater happiness from engaging in generous behaviors.

… as population size rises, generosity does not scale uniformly across all types of generous activities.

In summary, the consequences of generosity ripple outward … Beginning with the individual and micro-level: self-benefit entails consequences for the donor. Whether it is giving time, money, blood, or relational attention, generosity appears to benefit the giver, promoting better overall health and wellbeing. Rippling outward, generosity also promotes multiple consequences for interpersonal others. In marriages, being generous toward one’s spouse causes better outcomes for the couple and, for certain types of couples, promotes greater community generosity. Rippling outward to a third level, generosity in groups, organizations, and networks results in greater collective generosity and wellbeing. In a pay-it-forward mechanism, people who are the recipients of generosity in group settings cascade generosity onward and spread greater generosity throughout networks to new recipients, who in turn spread generosity onward. Rippling to the broadest level, generosity also appears to be beneficial for communities, cities, and societies generally (Gaudiani 2010). Although, of all the consequences of generosity, the broadest and most macro-level effects are, as of now, the least studied and thus least understood.

… generosity appears to have mostly positive consequences, across multiple social levels. Although, there are also some drawbacks to generosity, in terms of ways that collective giving can result in some group participants benefiting without carrying their full weight. Some studies indicate that punishments and other seemingly negative social mechanisms also result from generosity, but ultimately small-group enforcement of mild punishments appears to in turn promote greater generosity.

With regard to the consequences of generosity reviewed in this chapter, social scientists do not yet know enough about this domain to contribute robust understandings.

20 Mar 2023

Summary

There is no shortage of pressing problems in the world, enumerated by the United Nations (and respective Sustainable Development Goals), World Economic Forum, 80,000 hours, etc. These issues are highly interconnected, and making meaningful progress on one often requires domain knowledge on another. This is my attempt to map out those interdependencies and identify outsized areas of impact (w.r.t. problem prioritization, but also to identify fundamental topics/domains that one should learn about that are important to many systemic issues).

Takeaways include:

- Geopolitics, social unrest, the economy, and strong institutions are foundational to most issues. It’s difficult to make progress on an issue if one of these areas is in a poor state, so understanding general trends in them is important.

- Strategically prioritizing problems is important for effectiveness and efficiency, and priority is situational e.g. per country.

- Prioritizing basic and secondary needs (strong institutions, extreme poverty, access to essential services, gender equality, and governance) are perceived as more important than tackling higher-level systemic issues (e.g. climate change, urbanization).

- The Sustainable Development Goals typically synergize with one another (where success in one promotes success in the other), rather than posing trade-offs (where success in one comes at the cost of success in the other).

- None of the Sustainable Development Goals are fundamentally incompatible with another, but some have trade-offs that warrant careful consideration to support economic and social development within environmental limits.

My attempt at synthesis

Below is my basic attempt to draw connections between UN Global Issues. It was developed from reading summaries of each issue (supplemented by A Guide to SDG Interactions: from Science to Implementation), and noting challenges that block its progress, adjacent issues that will also benefit from its progress, or related topics that are necessary to understand it. It’s a superficial overview that lacks weighted importance between connections, and some issues are more thorough in drawing sub-issues and connections than others, but it provides a decent enough overview to understand systemic interactions.

An edge (arrow) from A → B indicates either A’s causality to B, or A’s importance in B’s solution. Nodes are sized based on how many outgoing edges they have, i.e. how causal or important they are to other issues. The original UN Global Issues are marked with a “UN” icon.

My conclusions are:

- Lack of access to basic services and gender inequality are at the root of many systemic issues (e.g. poverty, inequality, economic development)

- Similarly, economic development and the application of big data are “horizontal” beneath most issues and can advance progress on many issues simultaneously

Appendix

United Nations

The United Nations’ list of global issues reflect the issues the organization is trying to tackle through its Sustainable Development Goals, which aim to promote human development while balancing the economic, social, and environmental dimensions of sustainability. The SDGs represent a highly interlinked and indivisible agenda, with trade-offs and constraints in the implementation of goals to avoid detracting from others. Implementation is left up to each country, though the SDGs intentionally do not provide a plan of action or address the complexities and trade-offs that emerge.

SDGs In Order

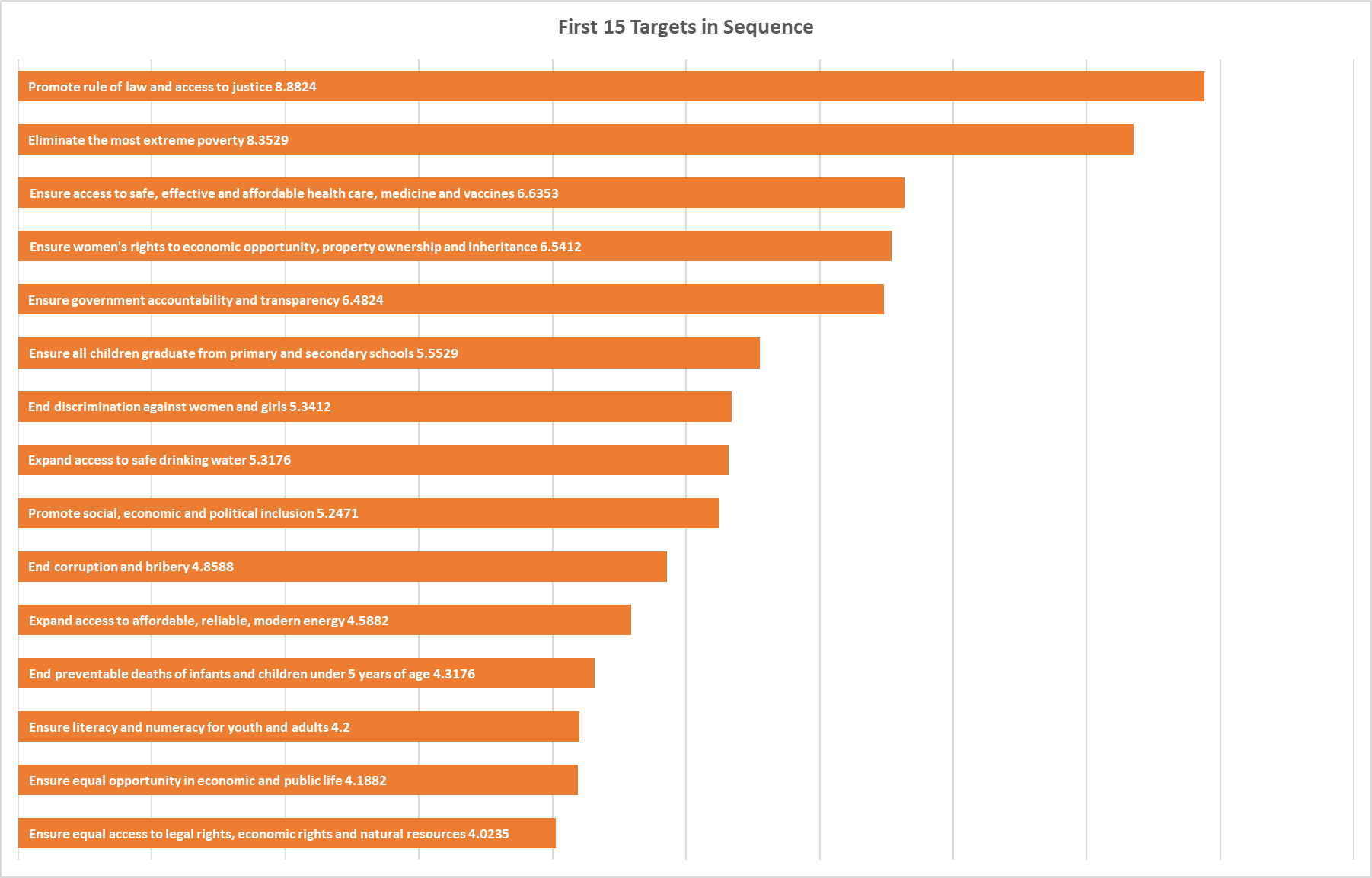

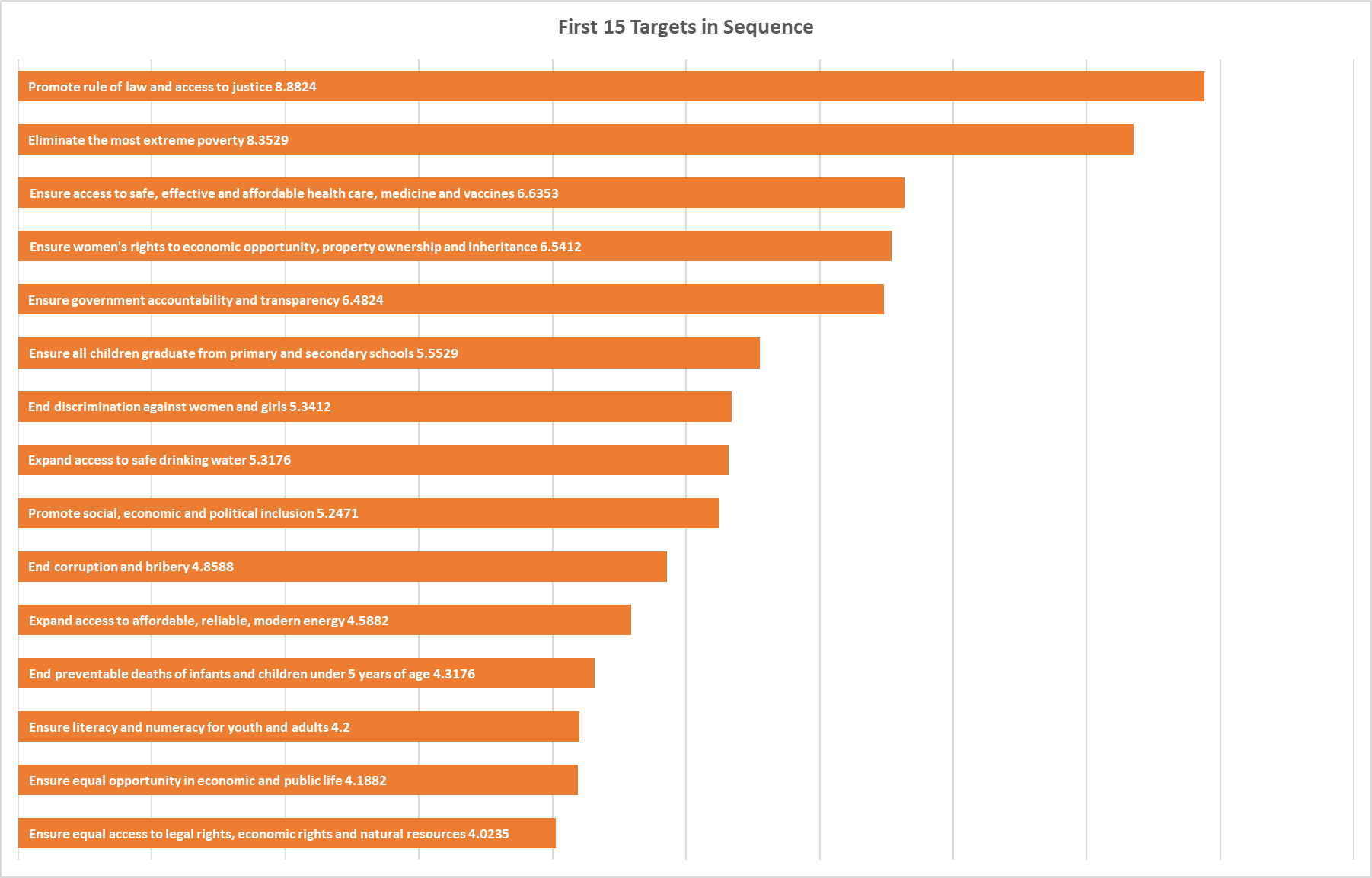

The SDGs have been criticized for their broad scope and lack of prioritization strategy (“[looking] more like an encyclopedia of development than a useful tool for action”). In response, New America and OECD created an ordering of the Sustainable Development Goals designed to optimize for stability in society and the state. They contend that a logical, ordered approach to tackling SDGs makes a significant difference in effectiveness over organizations and individuals pursuing their own specific issues due to self-interest. The ordering was created by surveying “economists, political scientists and social scientists working in public institutions, international organizations, foundations, universities, think tanks and civil society groups around the world”, and asking them to identify and sequence the first 20 SDG targets that should be tackled as part of an effort to fulfill all SDGs.

Targets to promote rule of law and access to justice, and eliminate the most extreme poverty, were perceived as significantly more important than the others:

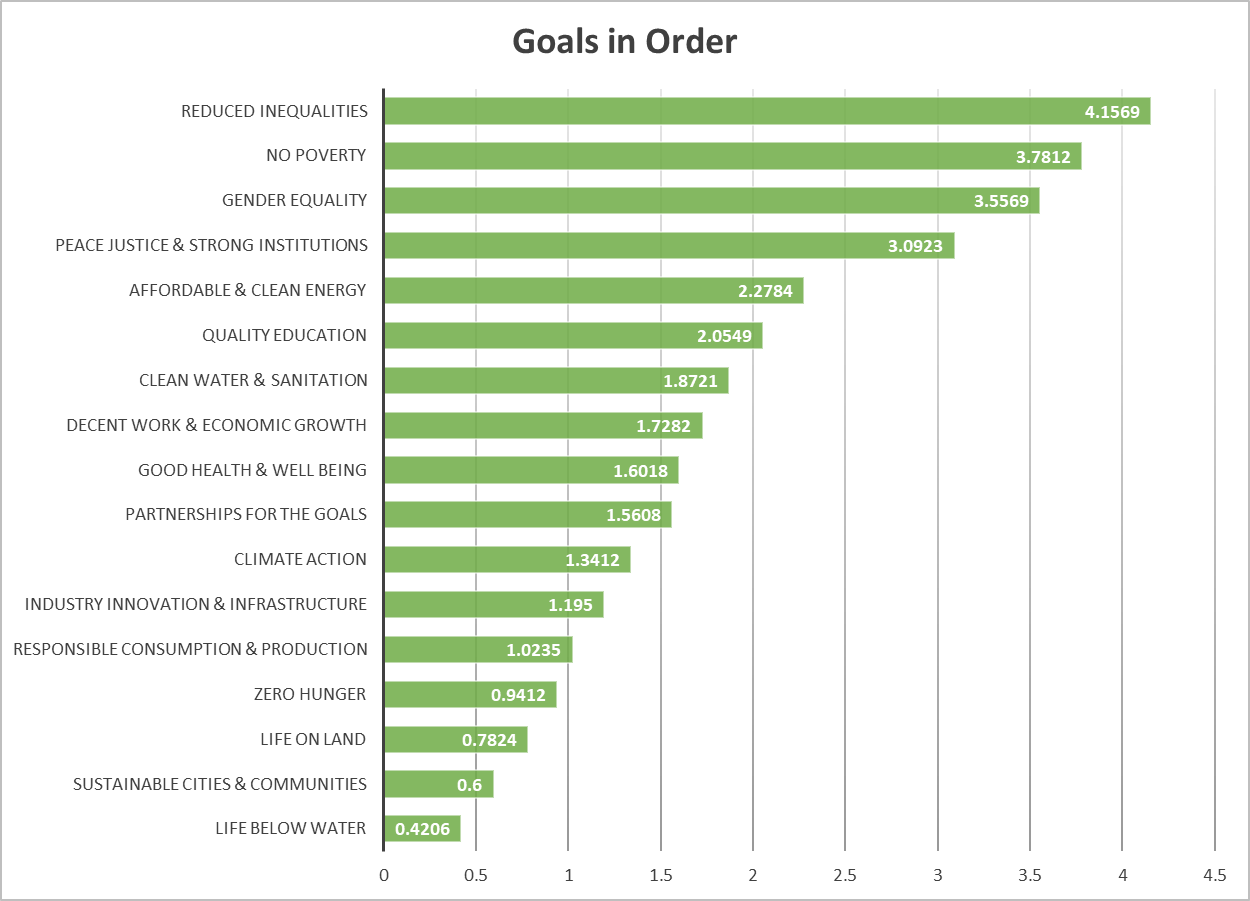

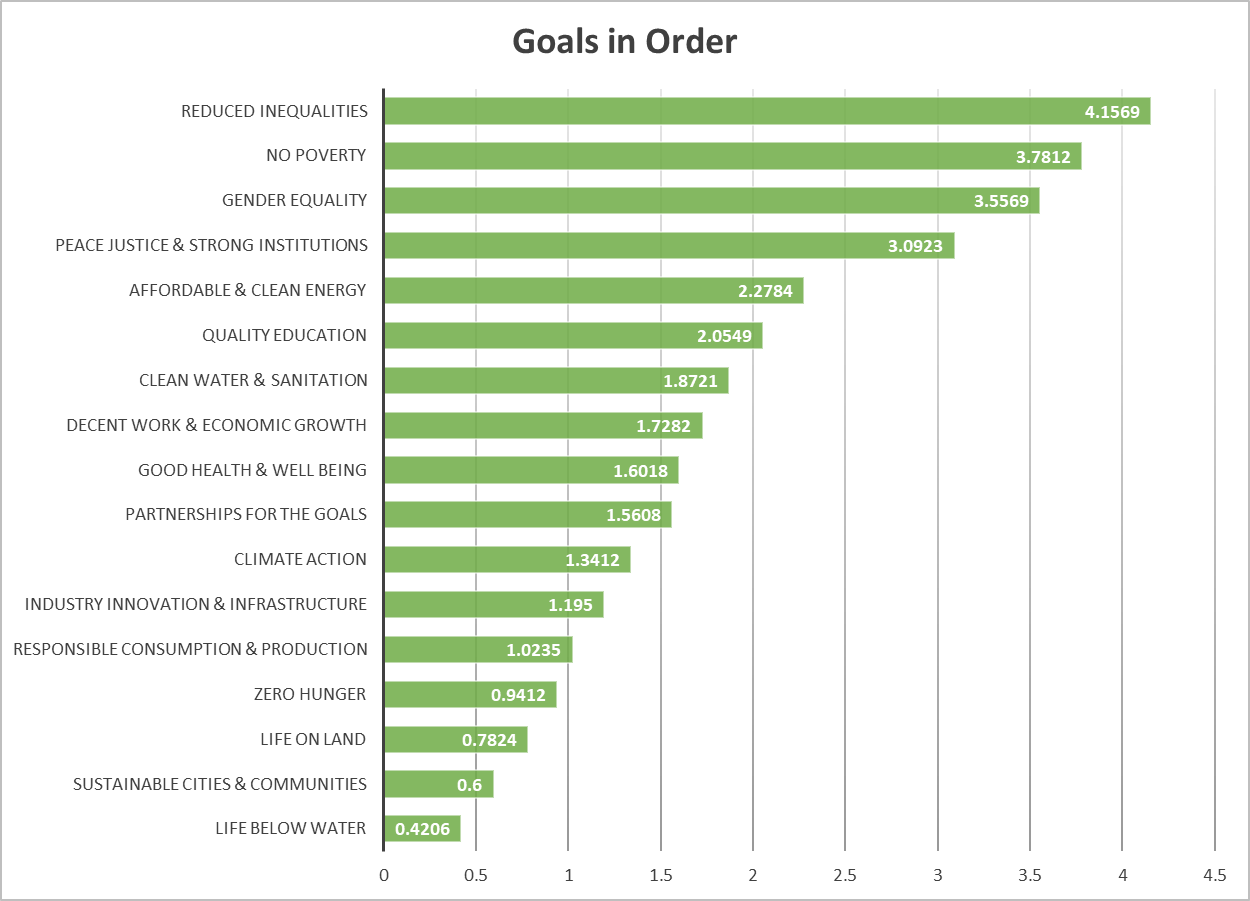

The targets chosen in the survey were mapped to their corresponding SDGs to rank the SDGs as well. Deviating from the target ordering, goals to reduce inequalities, eliminate poverty, achieve gender equality, and promote peace, justice, and strong institutions were perceived as significantly more important than the other SDGs:

The experts’ philosophies of prioritization were also categorized into approaches that optimize for empowering individuals vs. strengthening institutions, and having a deliberate, calculated approach vs. moving quickly to address the most pressing challenges. The majority of approaches were individualistic, with a relatively even split between deliberation vs. urgency.

SDG interactions (qualitative)

From A Guide to SDG Interactions: from Science to Implementation:

Although governments have stressed the integrated, indivisible and interlinked nature of the SDGs …, important interactions and interdependencies are generally not explicit in the description of the goals or their associated targets. … This report … [explores] the important interlinkages within and between these goals and associated targets to support a more strategic and integrated implementation. Specifically, the report presents a framework for characterising the range of positive and negative interactions between the various SDGs, … and tests this approach by applying it to an initial set of four SDGs: SDG2, SDG3, SDG7 and SDG14. This selection presents a mixture of key SDGs aimed at human well-being, ecosystem services and natural resources, but does not imply any prioritisation.

There aren’t many details on the report’s methodology, other than “the approach taken relied on an interpretive analytical process whereby research teams combine their knowledge and expert judgment with seeking of new evidence in the scientific literature and extensive deliberations about the character of different specific interactions”. I presume the teams mapped their understanding of target interactions to the numerical framework mentioned in the report, which categorizes the positivity or negativity of each interaction.

Some of my takeaways are:

This analysis found no fundamental incompatibilities between goals (i.e. where one target as defined in the 2030 Agenda would make it impossible to achieve another). However, it did identify a set of potential constraints and conditionalities that require coordinated policy interventions to shelter the most vulnerable groups, promote equitable access to services and development opportunities, and manage competing demands over natural resources to support economic and social development within environmental limits.

It should also be clear that a good development action is one where all negative interactions are avoided or at least minimised, while at the same time maximising significant positive interactions; but this by no means suggests that policymakers should avoid attempting progress in those targets and goals that are associated with significant negative interactions – it merely suggests that in these cases policymakers should tread more carefully when designing policies and strategies.

SDG16 (good governance) and SDG17 (means of implementation) are key to turning the potential for synergies into reality, although they are not always specifically highlighted as such throughout the report. For many if not all goals, having in place effective governance systems, institutions, partnerships, and intellectual and financial resources is key to an effective, efficient and coherent approach to implementation.

Given budgetary, political and resource constraints, as well as specific needs and policy agendas, countries are likely to prioritise certain goals, targets and indicators over others. As a result of the positive and negative interactions between goals and targets, this prioritisation could lead to negative developments for ‘nonprioritised’ goals and targets. … due to globalisation and increasing trade of goods and services, many policies and other interventions have implications that are transboundary in nature, such that pursuing objectives in one region can impact on other countries or regions’ pursuit of their objectives.

The following types of dependencies within a pair of goals/targets can be useful to contextualize their relationship/interactions:

- Directionality: whether the interaction is unidirectional, bidirectional, circular, or multiple

- Place-specific context: scale of the interaction, e.g. highly location-specific vs. generic across borders

- Governance: does poor governance create or amplify a negative relationship between the goals/targets?

- Technology: do technologies exist that can significantly mitigate the trade-off between the goals/targets?

- Time-frame: will the (positive or negative) interaction develop in real-time vs. over a long period of time?

Policies developed to address the SDGs should be coherent, i.e. systematically reduce conflicts and promote synergies between and within different policy areas to achieve policy objectives. Policy coherence is comprised of the following dimensions:

- Sectoral: coherent from one policy sector to another

- Transnational: observing to what extent the pursuit of objectives in one country will affect the ability of another to pursue its sovereign objectives

- Governance: coherent from one set of interventions to another

- e.g. legal frameworks, investment frameworks, and policy instruments all pull in the same direction

- It is often the case that while new policies and goals can be easily introduced, institutional capacities for implementation are not aligned with the new policy designs, because the former are commonly more difficult to develop

- Multilevel: coherent across multiple levels of government (international/national/local)

- Implementation: coherent along the implementation continuum: from policy objective, through instruments and measures agreed, to implementation on the ground

- The latter often deviates substantially from the original policy intentions, as actors make their interpretations and institutional barriers and drivers influence their response to the policy

Takeaways on specific SDG interactions are included in the synthesized interactions graph above.

SDG interactions (quantitative)

A Systematic Study of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Interactions builds upon the previous (ISCU) qualitative analysis of SDG interactions by performing a statistical analysis of SDG indicators from country and country-disaggregated data. They capture interaction synergies and trade-offs by identifying significant positive and negative correlations in the indicator data.

They found the following SDG pairs have the most synergies and trade-offs:

The observed positive correlations between the SDGs have mainly two explanations. First, indicators of the SDGs depicting higher synergies consist of development indicators that are part of the MDGs and components of several development indices …. Second, the observed higher synergies among some SDGs are an effect of having the same indicator for multiple SDGs.

Most trade-offs … can be linked to the traditional nonsustainability development paradigm focusing on economic growth to generate human welfare at the expenses of environmental sustainability …. On average developed countries provide better human welfare but are locked-in to larger environmental and material footprints which need to be substantially reduced to achieve SDG 12 (Responsible consumption and production).

We are aware that correlation does not imply causality. This means observed synergies between two SDG indicators could be independently related to another process driving both indicators and therefore resulting in correlations. However, because the correlation analysis is done for indicator pairs in each country individually, the existence of a large number of synergies (or trade-offs) suggests that the relation is widespread across many countries and most likely not appearing by chance.

Takeaways include:

- The conclusions from this quantitative study are largely in agreement with the qualitative ISCU study: there are typically more synergies than trade-offs within and among the SDGs in most countries, and fostering cross-sectoral and cross-goal synergetic relations will play a crucial role in operationalization of the SDG agenda.

- SDG 1 (No poverty) is associated with synergies across most SDGs and ranks five times in the global top-10 synergy pair list.

- Reducing poverty is statistically linked with progress in SDGs 3 (Good health and wellbeing), 4 (Quality education), 5 (Gender equality), 6 (Clean water and sanitation), or 10 (Reduced inequalities) for 75%–80% of the data pairs.

- Improvement of global health and well-being has highly been compatible with progress in SDGs 1 (Poverty reduction), 4 (Quality education), 5 (Gender equality), 6 (Provision of clean water and sanitation), and SDG 10 (Inequalities reduction) based on more than 70% of the data pairs.

- SDG 3 (Good health and well-being) was found to have a higher share of synergies with other SDGs in most of the countries and the world population …. Hence, a paradigm shift prioritizing good health and well-being, for example, by inter-sectoral and prevention based approaches, will have a greater impact than the conventional approaches … and will also leverage attainment of other SDGs.

- The global top 10 pairs with trade-offs either consist of SDG 12 (Responsible consumption and production) or 15 (Life on land).

- SDGs 8 (Decent work and economic growth), 9 (Industry, innovation, and infrastructure), 12 (Responsible consumption and production), and 15 (Life on land) are associated with a high fraction of trade-offs across SDGs.

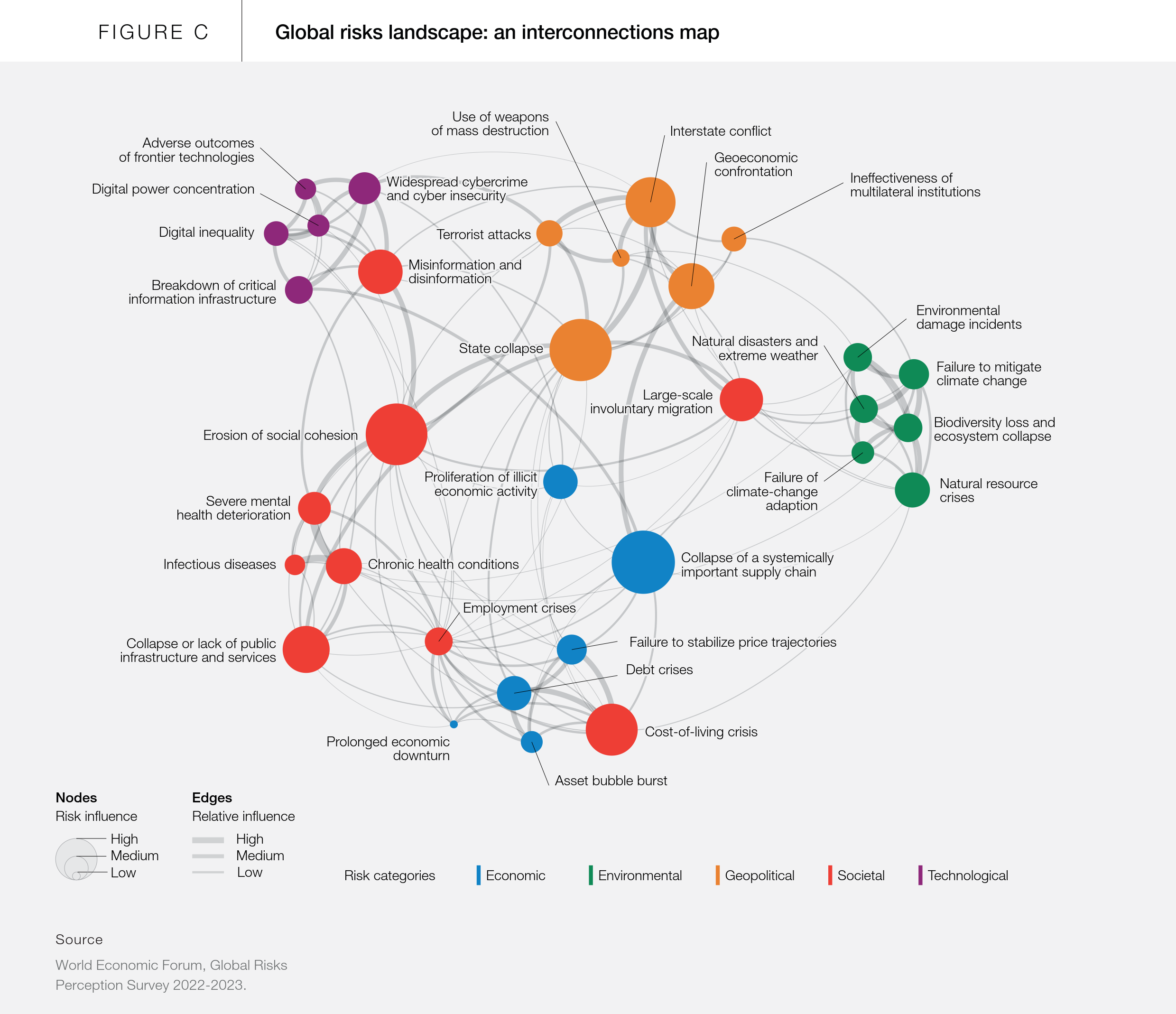

World Economic Forum

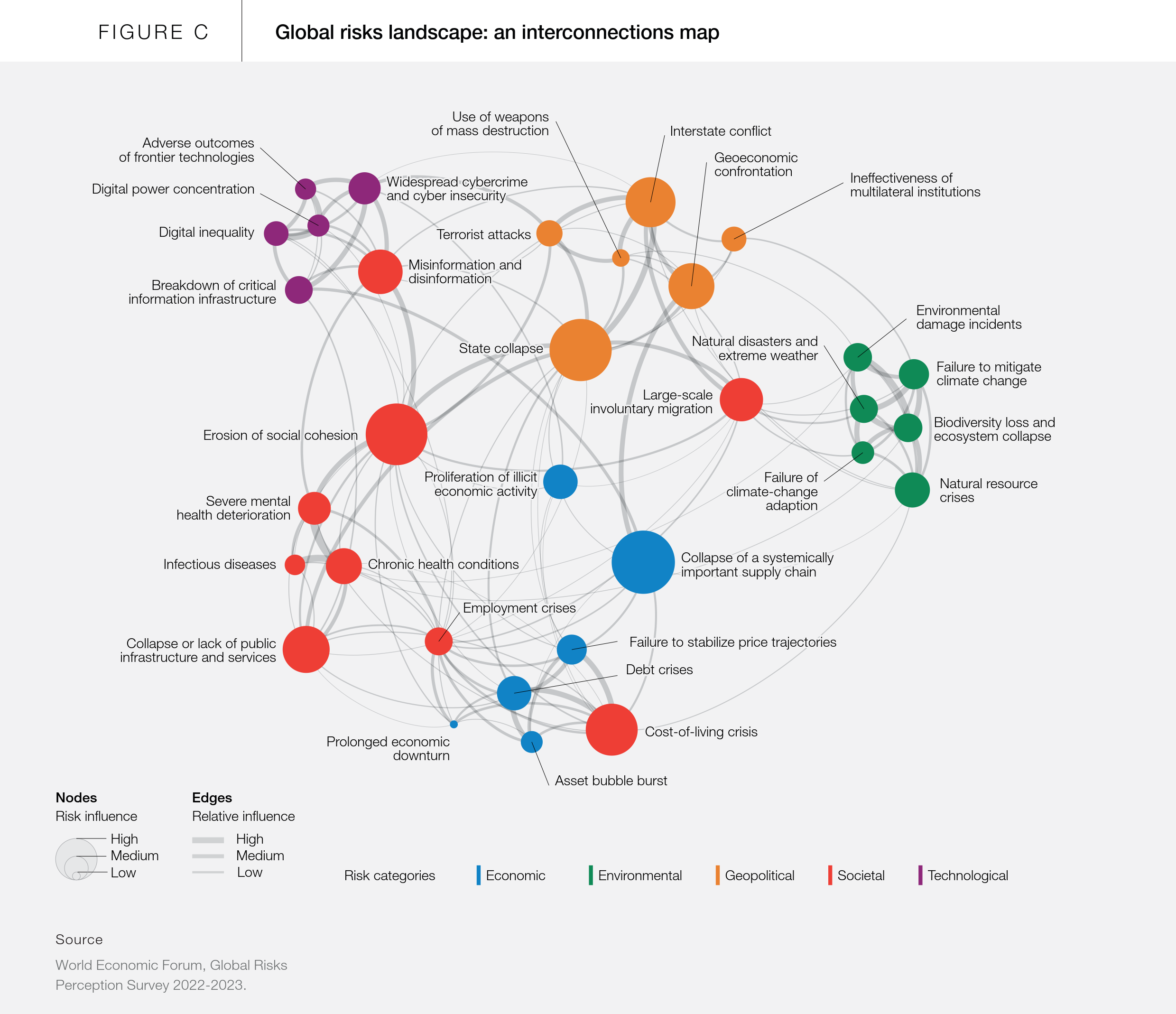

The World Economic Forum generates an annual Global Risks Report by surveying their “extensive network of academic, business, government, civil society and thought leaders” about their largest perceived global risks. These reports rank the importance of issues over short- (2-year), medium- (5-year), and long-term (10-year) horizons, and often feature a map of interconnections between issues with weighted causality, which is relevant to the objectives of this post.

However, it seems the risks are primarily relative to governments and businesses, have an elite-centric perspective, and do not consider fundamental issues affecting individuals (e.g. poverty and gender equality) to be “risks”. Additionally, the reports seem inconsistent in their long-term risk perceptions, and follow trends and FUD du jour. Nevertheless, they provide an additional perspective on interconnection and causality, to be taken with a grain of salt.

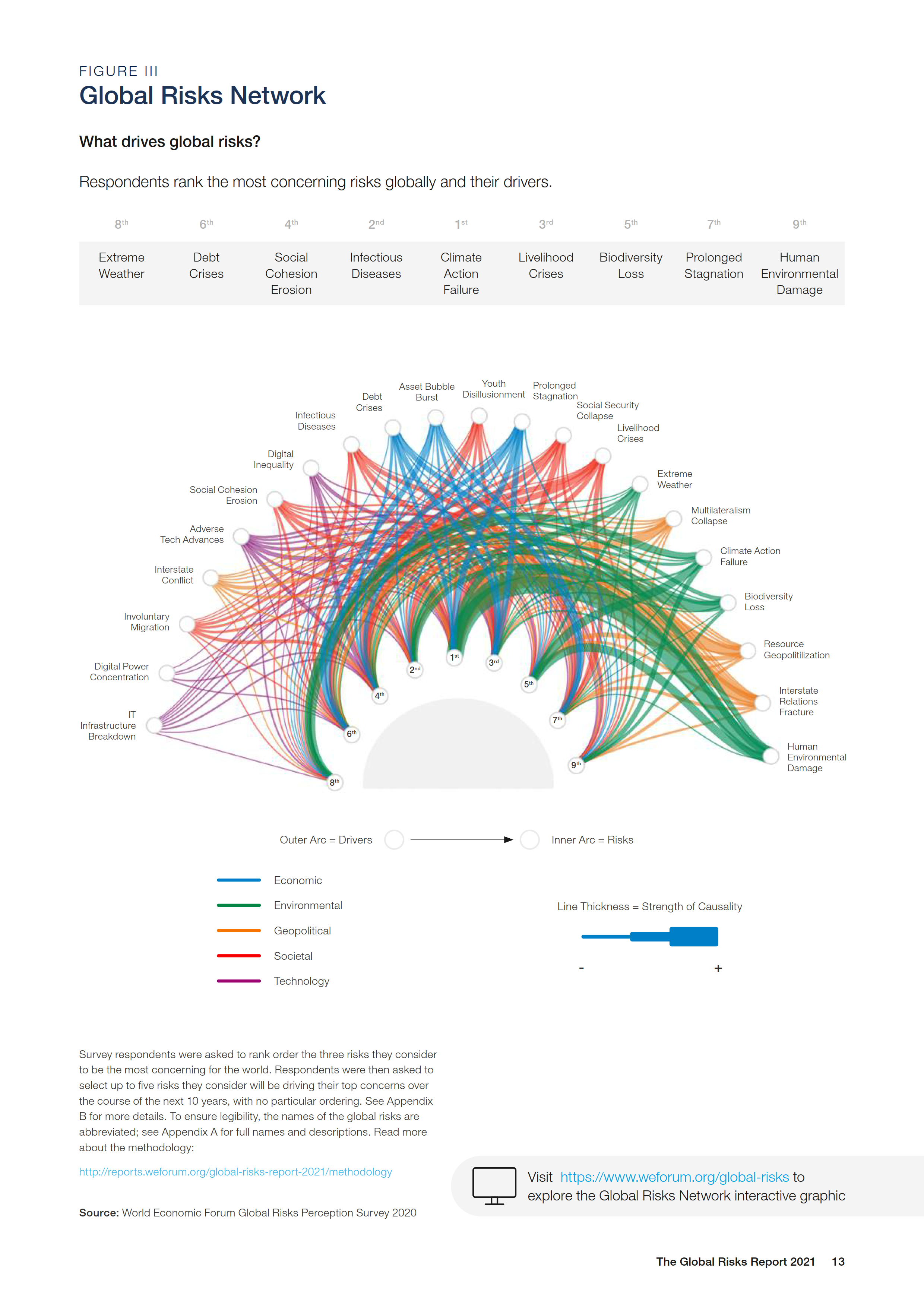

Causality

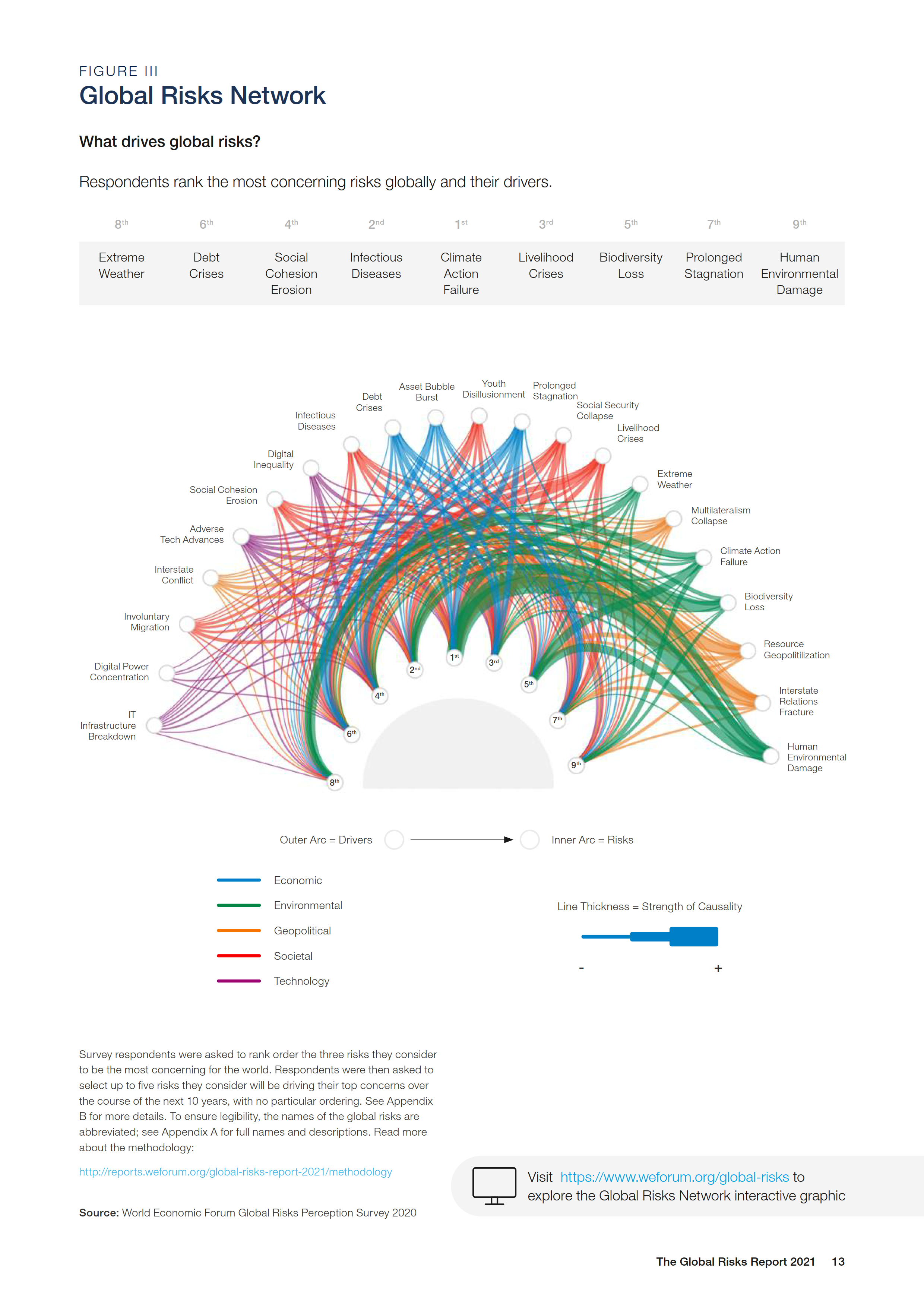

Since 2021, the WEF reports have included a section that analyzes causality and downstream effects between issues. These are included below, with my respective conclusions under each year.

In 2023, the following risks were identified as especially consequential if they were to be triggered. This doesn’t necessarily indicate high individual impact/severity of these risks, but rather high influence for exacerbating other issues. An interactive version is available here under the “Causes & Consequences” tab.

- Cohesion is tightly coupled between the societal, geopolitical, and economic spheres; if one sphere collapses, it has significant consequences for the others

2022’s report shows the perceived downstream effects of the top 5 most severe 10-year risks; interactive version here, under “Global Risks Effects”.

- Climate action failure leads to further damage in the environmental and societal spheres (involuntary migration, livelihood crises, and social cohesion erosion)

2021’s report shows the perceived drivers (opposite of 2022) of the top 5 most severe 10-year risks; interactive version here.

- Climate action failure and human environmental damage reinforce one another

- Climate action is impeded by geopolitical issues (interstate relations, resources, multilateralism), economic issues (stagnation, debt), and societal issues (livelihood crises, social cohesion erosion), in that order

- Livelihood crises are caused by a relatively even distribution of societal factors (social security collapse and diseases (COVID)), economic factors (stagnation and debt), and technological factors (to a lesser extent than the others; digital inequality and adverse tech advances)

- Social cohesion erosion is primarily driven by other societal factors (livelihood crises, social security collapse, youth disillusionment, involuntary migration), and technological factors to a lesser extent (digital inequality, adverse tech advances)

Interconnections

Prior to 2021, the reports analyzed risk interconnections (without causality) by surveying “the most strongly connected” pairs of global risks. Interactive versions of this section of the report are available for 2020, 2019, and 2018. Node size and edge weight are based on number of appearances (of a given risk, or pair of risks, respectively) in survey results.

Risk pairs that were consistently perceived as strongly connected include:

- State collapse or crisis & involuntary migration

- Interstate conflict & involuntary migration

- Unemployment & social instability

- Climate action failure & extreme weather

12 Mar 2022

Summary

Freedom and equality are typically presented as opposing values (in e.g. Sapiens, The Lessons of History). The different conceptions of each term, and how they’re interrelated, are explored in greater depth below. While various conceptions of equality do restrict individual liberties, the moral significance of these restrictions is subjective and depends on one’s values. Egalitarians view these restrictions as insignificant and worthwhile to enable others to enjoy a good life.

Freedom

“There is a whole range of possible interpretations or ‘conceptions’ of the single concept of liberty”, thus the overview below is incomplete; but it’s good enough for a model to add depth to the question (of whether freedom and equality are opposed).

- these types of freedom are not mutually exclusive; can enjoy two of them at the expense of the third

- for example, it’s possible to be institutionally oppressed without directly interfering with actions – i.e. it’s possible to lack republican freedom while maintaining negative freedom

- the positive and negative conceptions of freedom are credited to Isaiah Berlin, and the republican conception to Philip Pettit

- additional context and definitions are included from Elizabeth Anderson and other sources as linked above

- to sustain a free society over time, Anderson claims we should accept priority of republican over negative liberty (which endorses equality of authority)

- Anderson also claims “we should be skeptical of attempts to operationalize the conditions for nondomination in formal terms. Powerful agents are constantly devising ways to skirt around formal constraints to dominate others. Republican freedom is a sociologically complex condition not easily encapsulated in any simple set of necessary and sufficient conditions, nor easily realized through any particular set of laws.”

Why favor positive or republican over negative freedom?

Summary:

To block arguments that freedom requires substantial material equality, libertarians typically argue that rights to negative liberty override or constrain claims to positive liberty. This chapter will argue that, to the extent that libertarians want to support private property rights in terms of the importance of freedom to individuals, this strategy fails, because the freedom-based defense of private property rights depends on giving priority to positive or republican over negative freedom. Next, it is argued that the core rationale for inalienable rights depends on considerations of republican freedom. A regime of full contractual alienability of rights—on the priority of negative over republican freedom—is an unstable basis for a free society. It tends to shrink the domains in which individuals interact as free and independent persons, and expand the domains in which they interact on terms of domination and subordination. To sustain a free society over time, we should accept the priority of republican over negative liberty. This is to endorse a kind of authority egalitarianism. The chapter concludes with some reflections on how the values of freedom and equality bear on the definition of property rights. The result will be a qualified defense of some core features of social democratic orders.

Further detail:

Arguments for the priority of negative over positive freedom with respect to property rights run into more fundamental difficulties. A regime of perfect negative freedom with respect to property is one of Hohfeldian privileges only, not of rights. A negative liberty is a privilege to act in some way without state interference or liability for damages to another for the way one acts. The correlate to A’s privilege is that others lack any right to demand state assistance in constraining A’s liberty to act in that way. There is nothing conceptually incoherent in a situation where multiple persons have a privilege with respect to the same rival good: consider the rules of basketball, which permit members of either team to compete for possession of the ball, and even to “steal” the ball from opponents. If the other team exercises its liberty to steal the ball, the original possessor cannot appeal to the referee to get it back.

No sound argument for a regime of property rights can rely on considerations of negative liberty alone. Rights entail that others have correlative duties. To have a property right to something is to have a claim against others, enforceable by the state, that they not act in particular ways with respect to that thing. Property rights, by definition, are massive constraints on negative liberty: to secure the right of a single individual owner to some property, the negative liberty of everyone else—billions of people—must be constrained. Judged by a metric of negative liberty alone, recognition of property rights inherently amounts to a massive net loss of total negative freedom. The argument applies equally well to rights in one’s person, showing again the inability of considerations of negative liberty alone to ground rights. “It is impossible to create rights, to impose obligations, to protect the person, life, reputation, property, subsistence, or liberty itself, but at the expense of liberty” (Bentham, 1838–1843: I.1, 301).

(The above paragraph also makes the case for the conclusion at the end of this post.)

What could justify this gigantic net loss of negative liberty? If we want to defend this loss as a net gain in overall freedom, we must do so by appealing to one of the other conceptions of freedom—positive freedom, or republican freedom. Excellent arguments can be provided to defend private property rights in terms of positive freedom. Someone who has invested their labor in some external good with the aim of creating something worth more than the original raw materials has a vital interest in assurance that they will have effective access to this good in the future. Such assurance requires the state’s assistance in securing that good against others’ negative liberty interest in taking possession of it. To have a claim to the state’s assistance in securing effective access to a good, against others’ negative liberty interests in it, is to have a right to positive freedom.

Considerations of republican freedom also supply excellent arguments for private property. In a system of privileges alone, contests over possession of external objects would be settled in the interests of the stronger parties. Because individuals need access to external goods to survive, the stronger could then condition others’ access on their subjection to the possessors’ arbitrary will. Only a system of private property rights can protect the weaker from domination by the stronger. The republican argument for rights in one’s own body follows even more immediately from such considerations, since to be an object of others’ possession is per se to be dominated by them.

(All quotes are from Elizabeth Anderson.)

Equality

Similarly to freedom, (in)equality is not just a single principle, but rather a complex group of principles that form the basis of today’s egalitarianism. Different principles yield different answers, and no single notion of equality can sweep the field. The sections below provide an overview of some of its different conceptions; they are incomplete similar to freedom above, but are sufficient models to add depth to the question.

Relational Equality

Relational equality aims to reduce or eliminate certain status differences in social interactions. Some of its forms include (from Elizabeth Anderson):

| |

Equality of standing |

Equality of esteem |

Equality of authority |

| Hierarchy (i.e. the opposite of equality) of this type looks like |

interests of superiors > interests of inferiors |

esteem of few > esteem of rest |

arbitrary commands to subordinates who must comply |

| *In the lens of distributive inequality, proponents of this relational type are concerned with… |

distributive justice (rules that determine fair distribution of economic gains, to help those less well off) |

glorifying the rich due to wealth (and stigmatizing the poor) |

government by the wealthy |

| Example: members of society… |

are treated as equals by the state and in institutions of civil society |

are recognized as bearing equal dignity and respect |

have equal votes and access to political participation in democratic states |

- these three types of hierarchy (i.e. the opposite of equality) usually reinforce each other (i.e. all three types of hierarchy at once)

- *these connections between relational equality and distributive equality are mainly causal

Distributive Equality

Theories of distributive equality offer accounts of what should be equalized in the economic sphere.

Notes from the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

- most can be understood as applications of the presumption of equality, where everyone should get an equal share of the distribution unless certain types of differences are relevant, and justify (through universally acceptable reasons) unequal shares

- the equality required in the economic sphere is complex, taking account of several positions that – each according to the presumption of equality – justify a turn away from equality

- a salient problem here is what constitutes justified exceptions to equal distribution of goods, the main subfield in the debate over adequate conceptions of distributive equality and its currency

- the following factors are usually considered eligible for justified unequal treatment:

- need or differing natural disadvantages (e.g. disabilities)

- existing rights or claims (e.g. private property)

- differences in the performance of special services (e.g. desert, efforts, or sacrifices)

- efficiency

- compensation for direct and indirect or structural discrimination (e.g. affirmative action)

- every effort to interpret the concept of equality and apply its principles (e.g. presumption of equality) demands a precise measure of the parameters of equality – we need to know the dimensions within which the striving for equality is morally relevant

- here is an overview of the seven most prominent conceptions of distributive equality, with some discussion on their objections

Notes from Elizabeth Anderson:

- any attempt to enforce strict material equality across large populations under modern economic conditions would require a totalitarian state; this is “true and of great historical importance” (e.g. communism), but virtually no one today advocates for this

- concern for distributive justice—specifically, how the rules that determine the fair division of gains from social cooperation should be designed—can be cast in terms of the question: what rules would free people of equal standing choose, with an eye to also sustaining their equal social relations?

Absent from this list of conceptions of equality is any notion of equality considered as a bare pattern in the distribution of goods, independent of how those goods were brought about, the social relations through which they came to be possessed, or the social relations they tend to cause. Some people think that it is a bad thing if one person is worse off than another due to sheer luck (Arneson, 2000; Temkin, 2003). I do not share this intuition. Suppose a temperamentally happy baby is born, and then another is born that is even happier. The first is now worse off than the second, through sheer luck. This fact is no injustice and harms no one’s interests. Nor does it make the world a worse place. Even if it did, it would still be irrelevant in a liberal political order, as concern for the value of the world apart from any connection to human welfare, interests, or freedom fails even the most lax standard of liberal neutrality.

Relationships between these types

graph TB

subgraph freedom[Freedom]

negative_freedom["Negative

(#quot;noninterference#quot;)"]

positive_freedom["Positive

(#quot;opportunities#quot;)"]

republican_freedom["Republican

(#quot;non-domination#quot;)"]

takes_priority_over(["takes priority over"])

end

subgraph equality[Equality]

esteem_equality[Esteem]

standing_equality[Standing]

authority_equality[Authority]

end

republican_freedom --> takes_priority_over --> negative_freedom

takes_priority_over -->|"doing so endorses"| authority_equality

authority_equality -->|"(lack of) causes

most important infringements of*"| republican_freedom

republican_freedom -->|"requires"| authority_equality

republican_freedom ---|"#quot;deep affinity#quot;,

but not conceptually identical*"| authority_equality

*There is a deep affinity between republican freedom as nondomination and authority egalitarianism. These are not conceptually identical. Domination can be realized in an isolated, transient interpersonal case (consider a kidnapper and his victim). Authoritarian hierarchy is institutionalized, enduring, and group-based. Yet authority hierarchies cause the most important infringements of republican freedom. Historically, the radical republican tradition, from the Levellers to the radical wing of the Republican party through Reconstruction, saw the two causes of freedom and equality as united: to be free was to not be subject to the arbitrary will of others. This required elimination of the authoritarian powers of dominant classes, whether of the king, feudal landlords, or slaveholders. Republican freedom for all is incompatible with authoritarian hierarchy and hence requires some form of authority egalitarianism.

General diagram of concepts

graph TB

freedom["Freedom"]

relational_equality["Relational

equality"]

conventional_equality["Conventional ideas

of equality

(e.g. distributive)"]

hierarchy["Hierarchy"]

oppression["Oppression

(of all forms of freedom)"]

freedom ---|"Harari claims are opposed;

Anderson claims not"| relational_equality

freedom ---|"opposed

(Anderson)"| oppression

relational_equality -->|"egalitarians oppose hierarchies

and aim to replace w/

institutions w/ greater equality"| hierarchy

relational_equality -->|"causal"| conventional_equality

hierarchy -->|"can lead to*"| oppression

*See this model for the connection between hierarchy and oppression

Are freedom and equality fundamentally opposed?

It depends on how you view freedom and how you view equality. Are personal liberties restricted to uphold the types of relational equality defined above? Yes - there is now a smaller spectrum of acceptable actions. The same goes for economic liberty (the freedom to make contracts, acquire property, and exchange goods) when upholding distributive (i.e. economic) equality.

But are those restrictions significant? That depends on your stance on egalitarianism. If you value equality as a fundamental goal of justice, you would be willing to make (relatively insignificant) sacrifices of these freedoms (i.e. would not want to take actions that oppress others) so others can enjoy a good life.

Quoting Anderson, “moderate egalitarianism of the social democratic type has proved compatible with democracy, extensive civil liberties, and substantial if constrained market freedoms. … the ideal of a free society of equals is not an oxymoron: not only is relational equality not fundamentally opposed to freedom, in certain senses equality is needed for freedom. Inequality upsets liberty.”

Additionally, Giebler and Merkel have empirically concluded both freedom and equality can be maximized at the same time.