Data, Information, Knowledge, Wisdom

24 Sep 2020The DIKW model is a conceptual relationship between data, information, knowledge, and wisdom. Several variants of this model exist, which lack consensus on the definition of each term, and the transformations between them.

Russell Ackoff’s 1989 paper From Data to Wisdom is often quoted to define these terms:

Wisdom is located at the top of a hierarchy of types, types of content of the human mind. Descending from wisdom there are understanding, knowledge, information, and, at the bottom, data. Each of these includes the categories that fall below it – for example, there can be no wisdom without knowledge.

Data are symbols that represent properties of objects, events and their environments. They are products of observation. … Information, as noted, is extracted from data by analysis … Data, like metallic ores, are of no value until they are processed into a useable [sic] (i.e. relevant) form. Therefore, the difference between data and information is functional, not structural, but data are usually reduced when they are transformed into information.

Information is contained in descriptions, answers to questions that begin with words such as who, what, where, when, and how many.

Knowledge is know-how, for example, how a system works. It is what makes possible the transformation of information into instructions. It makes control of a system possible. To control a system is to make it work efficiently. … Knowledge can be obtained in two ways: either from transmission by another who has it, by instruction, or by extracting it from experience. In either case, the acquisition of knowledge is learning.

Learning and adaptation may take place by trial and error or systematically by detection of error and its correction. Diagnosis is the identification of the cause of error and prescription is instruction directed at its correction. Systematic learning and adaptation require understanding error, knowing why it was made and how to correct it.

Information, like news, ages relatively rapidly. Knowledge has a longer lifespan, although inevitably it too becomes obsolete. Understanding has an aura of permanence around it. Wisdom, unless lost, is permanent …

… information, knowledge and understanding all focus on efficiency. Wisdom adds value, which requires the mental function we call judgement. Evaluations of efficiency all are based on a logic which, in principle, can be specified, and therefore can be programmed and automated. These principles are general and impersonal. We can speak of the efficiency of an act independent of the actor. Not so for judgment. The value of an act is never independent of the actor, and seldom is the same for two actors even when they act in the same way. Efficiency is inferrable [sic] from appropriate grounds; ethical and aesthetic values are not. They are unique and personal.

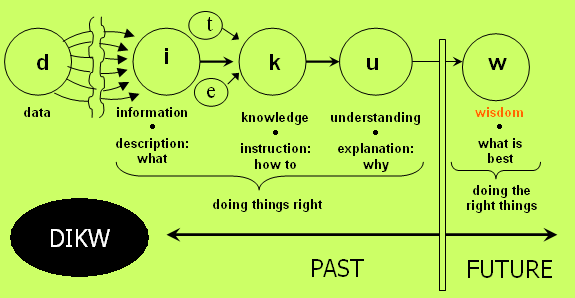

The DIKW model is summarized in the following flowchart (from Wikipedia):

[T & E meaning tacit and explicit]

Gene Bellinger et al. present an alternative view:

Personally I contend that the sequence is a bit less involved than described by Ackoff. The following diagram represents the transitions from data, to information, to knowledge, and finally to wisdom, and it is understanding that support [sic] the transition from each stage to the next. Understanding is not a separate level of its own.

The DIKW model has its limitations; it isn’t universally applicable, and can break down when analyzing the semantic definitions of each step (e.g. drawing the line between data and information). Though I find the model is still a useful concept, which illustrates:

- the “graduation” of data, information, and knowledge (however you want to define them) into increasingly simplified but useful forms

- the relationship between stages of the DIKW pyramid and timelessness

- the difference between operational efficiency (doing things right), and directional effectiveness (doing the right things)

- doing the right thing requires knowing how the system currently works

- how the value of an act differs between individuals